Wayne Byres Chairman APRA has a great deal on his agenda, today in a speech he highlighted six issues that are likely to keep APRA particularly busy in 2016. The first three of these are especially relevant for banks and other ADIs; the other three may be of interest more broadly. Of note is the fact that whilst no Australian banks are G-SIBs, regulatory models based on G-SIBs will be applied. More capital will be needed.

Unquestionably strong

As I’m sure everyone in this room knows, the first recommendation of the FSI was that APRA should:

“set capital standards such that Australian authorised deposit-taking institution capital ratios are unquestionably strong.”

The Government’s response to the FSI agreed with this objective, and tasked APRA to get this done by the end of 2016. However, anyone who follows international banking regulation will also know that there are many issues still under discussion. Even if we could quickly agree domestically what an unquestionably strong bank looked like, we are not entirely masters of our own destiny: we must also be mindful of international developments, given the important foundational role played by the Basel Committee’s standards. Settling on a framework that makes sense for Australia, while at the same time continuing to meet international standards, will require a lot of time and attention during the year ahead. The task is quite manageable, but will require industry participants to be ready to constructively participate in the debate.

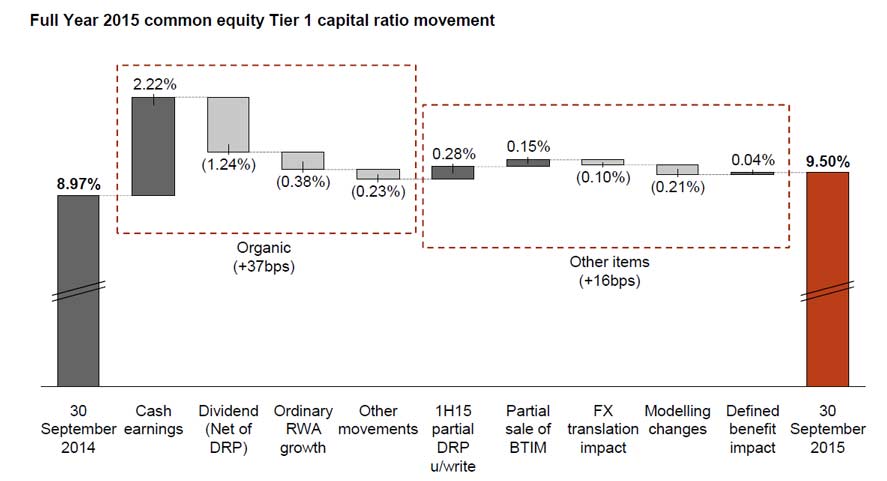

We are, of course, fortunate not to be starting from a position of weakness. We continue to have a soundly-capitalised banking system overall in Australia and, with the aid of recent capital raisings, the relative positioning of the major bank capital ratios against their international peers is much closer to that recommended by the FSI. That means that, given where we are today, APRA and the banking industry have time to manage the transition to any new requirements in an orderly fashion.

One important point I have made elsewhere is that an unquestionably strong ADI requires more than just plenty of capital. We need to think about ‘unquestionably strong’ in the context of the other risks to which an ADI is exposed, and the environment in which it operates.

Funding profile of the banking system

That is a natural point to turn to the funding profile of the banking system.

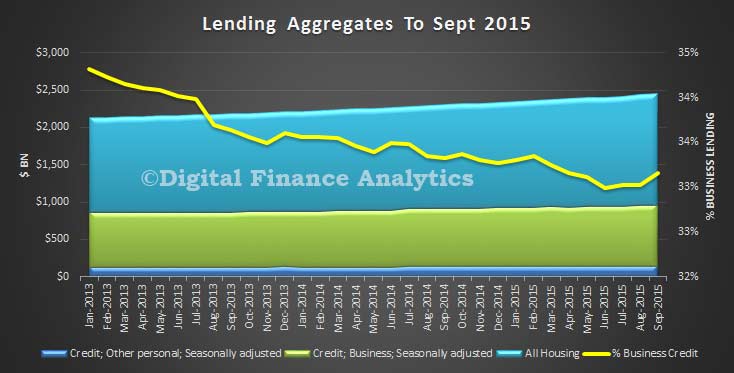

It is well known that the Australian banking system has a relatively high dependence on offshore funding. Taking steps to ensure that, even during times of stress, foreign creditors will be more likely to maintain confidence in the viability and creditworthiness of Australian ADIs was an important part of the rationale for the FSI’s recommendation for ADI capital to be made unquestionably strong.

It will not surprise you to hear me say that, in such circumstances, strengthening capital ratios certainly makes sense. But it should not be the only solution we employ. The introduction of global liquidity and funding standards in Basel III – the 30-day Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), and the longer-term Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) – are significant and complementary additions to the regulatory framework, and hence the resilience of the banking system, in this country.

The LCR was introduced for a group of larger banks at the beginning of this year and, in simple terms, substantially lifted the quantity and quality of liquidity held by banks, providing them with much greater capacity to manage periods of liquidity stress.

The NSFR, which provides a longer-term funding mismatch measure to complement the short-term LCR, is not due to come into effect until 2018. To assist with its orderly introduction, however, APRA will begin consultation in the near future on the Australian implementation of the NSFR, and the consultation and review process will no doubt occupy much of 2016. The new standard is designed to guard against excessive funding of long-term illiquid assets with short-term, unstable funding – a combination that proved dangerous when interbank funding and capital markets seized up in 2008. As things stand, some further adjustment to Australian bank maturity profiles is likely to be needed over time to truly strengthen their resilience, continuing the trend of recent years for the banking system to seek more stable sources of funding1.

Total loss absorbing capacity

Nevertheless, as much as we try to reduce the probability that financial firms will reach the point of failure, there can be no guarantees.

Acknowledging this, the Financial Stability Board (FSB) has been working on a new international standard for globally-systemically important banks (G-SIBs) to have a minimum amount of total loss absorbing capacity (TLAC). The overarching objective of the TLAC requirement is to ensure that G-SIBs have sufficient loss absorbency to enable the authorities to implement an orderly resolution which:

- minimises the impact on financial stability;

- maintains critical functions; and

- avoids exposing taxpayers to loss.

Although Australia has no G-SIBs, the FSI recommended the implementation of a domestic TLAC framework in line with emerging international practice. The Government’s response endorsed APRA to implement this recommendation, and I am sure we will not be alone in extending the TLAC regime beyond G-SIBs.

Assuming the international ground rules are settled by the end of this year, APRA will begin discussions on an Australian framework for loss absorbing and recapitalisation capacity during the course of 2016, in consultation with the members of the Council of Financial Regulators, and other interested stakeholders. The FSI suggested that Australia should not get ahead of international developments, and this is an area – perhaps more than most others – where the devil is in the detail, so it makes good sense that we hasten slowly.

Inevitably, there are going to be some tricky technical issues to resolve, including clarity over the mechanisms and triggers under which holders of particular instruments will absorb losses. On this issue, we are seeing a range of approaches internationally: from purely contractual triggers to statutory tools which vary widely in their scope. Given these global developments, we will have the benefit of a variety of thinking in this area as we progress our work.

But as well as monitoring international developments, it will clearly be important to consider what best suits the particular characteristics of the Australian financial system. This will include consideration of the increased ‘going concern’ loss absorbency being provided by our work to ensure Australian ADIs have unquestionably strong capital ratios. In addition, we already have a form of ‘gone concern’ loss absorbency through Tier 2 capital instruments, so the interaction with the capital framework will be an important consideration, as will providing for appropriate transition periods for building up any additional loss absorbing capacity.

Powers for dealing with failing firms

Moving beyond TLAC, and to issues that extend beyond ADIs, APRA’s current crisis resolution powers are a vital but often overlooked component of the prudential framework.

The global financial crisis put the spotlight on the lack of credible resolution options in many jurisdictions: indeed, the inability of regulators to resolve failing financial firms often exacerbated the crisis, and quickly led to the need for significant public sector support. The FSB has since established the Key Attributes of Effective Resolution Regimes (Key Attributes) to provide an international standard on financial crisis resolution. As noted in the FSI’s Final Report, there are some gaps and deficiencies in the Australian resolution framework when compared with the Key Attributes. We were therefore pleased to see the Government endorse improvements to APRA’s crisis management powers as a matter of priority.

Many of these legislative measures were initially raised in a September 2012 Consultation Paper, Strengthening APRA’s Crisis Management Powers, and included broader investigation powers; strengthened directions powers; improved group resolution powers; enhanced powers to deal with branches of foreign banks; and more robust immunities to statutory and judicial managers.

Cumulatively, these proposals will significantly enhance APRA’s resolution toolkit and align our powers more closely with international expectations. We certainly hope to use these powers rarely, but ensuring our capacity to deal with a distressed firm is robust and effective is a low-cost investment in protecting the interests of beneficiaries of regulated firms, and the stability of the financial system more broadly, without putting taxpayer funds at risk.

Of course, having a wide set of powers is not all that is needed. Crisis planning is also a critical, and the Key Attributes require jurisdictions to put in place processes for recovery and resolution planning for relevant firms. On recovery planning, APRA will be working further with larger ADIs (and in due course other relevant firms) to ensure they have plans that are credible – that is, a realistic and continuously-reviewed menu of actions that can be practically implemented in stressed operating conditions. On resolution planning, we will be commencing more detailed work on the planning required to ensure that we are able to use our resolution powers when needed. Although resolution plans are the responsibility of regulators, these plans will require the input of relevant firms and, potentially, consideration of pre-positioning measures that could help to improve resolvability.

Governance and culture

Regulators have a task to reduce the risk of a repeat of the sins of the past, but so do financial firms themselves.

I’ve made the point elsewhere that building up capital and liquidity, and ensuring loss absorbing capacity in the event of failure, will undoubtedly make for a more resilient financial system, but they will only offer a partial remedy to the problems that were experienced unless there are behavioural changes within financial firms as well. At the heart of that challenge are the related topics of governance, culture and remuneration. That is why we have recently created a new team within APRA to provide dedicated expertise on these issues. To be clear, we are not proposing significant new policy here: the team’s work will primarily focus, at least in its early stages, on improving our supervisory scrutiny of the specific requirements set out in existing prudential standards.

Under the broad heading of governance, culture and remuneration, we obviously can’t do everything and be everywhere at once. Our immediate priority is the area of risk culture, and in particular how banks and insurers are implementing the requirements of CPS220 Risk Management. As many of you know, this standard came into effect at the beginning of this year and, amongst other things, contains an ostensibly simple requirement for Boards to form a view of the risk culture in the firm, and the extent to which that culture supports the ability of the firm to operate consistently within its risk appetite.

Forming a view sounds relatively simple, but making sure that the Board’s view of risk culture is well-informed and reliable is more challenging. Therefore our first step will be to undertake a stocktake of practices that Boards are employing to fulfil this obligation. This stocktake will not only help us to refine and hone our supervisory approach to assessing risk culture, but will also hopefully help firms benchmark their own practices and understand a little better how they stack up against their peers.

Our next area of priority will be to review the current state of remuneration arrangements within ADIs and insurers. Specific requirements came into force in 2010 with the goal of ensuring personal rewards appropriately take account of risk-taking behaviour. These requirements are no longer new, so we will be looking to see that after the initial period of implementation, they are now fully in force and meaningfully applied. We’ll also be comparing Australian approaches with current and emerging international thinking – not necessarily to copy what’s done offshore, but at least make sure we are fully aware of differences in industry and regulatory practices and satisfy ourselves that we are not falling ‘behind the game’ due to any inattention to the issue.

Technology

The final issue I wanted to touch on is technology, particularly as the organisers of this event were keen to make technology a theme for the discussions. There is no doubt that technology, the innovations it brings, and the way in which it is changing the way financial services are provided, are increasingly topical. But, without in any way dismissing the increasing importance of the issue, it is not new.

APRA has employed a small but proactive team of IT experts for about the past 15 years, and the effective management of technology-related issues has always been a large part of their agenda. For example, on the risk side of things we have for a long time been focussed on ensuring that boards are educated and well-informed regarding cyber-risk; management has strategies and plans to address the evolving forms of cyber-risk; firms undertake penetration testing (ethical hacking), vulnerability management and testing, and have a systematic approach to managing and securing operating systems and software; and firms are able to detect cyber incidents in a timely manner, and possess response and recovery capability for plausible scenarios. We have done this not just for APRA-regulated firms, but also on occasion for systemically-important service providers.

We have used this work to develop guidance on good practice. For example, in 2010 we published a practice guide CPG 234 Management of Security Risk in Information and Information Technology. This is both principles- and risk-based, and continues to be relevant despite the rapidly evolving environment. More recently, we have published an information paper on Outsourcing involving Shared Computing Services (including Cloud). Outsourcing of various technology functions to service providers is not new, but the information paper responds to a trend for sharing services across a larger cross-section of entities (including non-financial industry entities) and the introduction of higher-order shared computing services (e.g. software). We have no wish to try to hold back the tide; we simply wish to ensure that the risks it involves are managed adequately. That will remain a major focus in the year ahead.

As firms continue to increase the openness of their systems (including greater use of digital channels), regulators like APRA need to evolve their supervisory approaches to respond to the changing risk profile. Moreover, we also need to monitor the broader strategic shifts that are underway, given the potential for new technologies to challenge the revenue streams of existing financial firms. New entrants and innovations that nip at the heels of the existing players, and keep them on their toes, are a positive for the Australia community. We should welcome them. But we also need to watch for the emergence of new risks, and the transfer of activities outside the regulatory net that the community expects to be appropriately regulated. Like regulated firms, we regulators will also need to be on our toes.