At its meeting today, the Board decided to leave the cash rate unchanged at 2.0 per cent.

The global economy is expanding at a moderate pace, but some key commodity prices are much lower than a year ago. Much of this trend appears to reflect increased supply, including from Australia. Australia’s terms of trade are falling nonetheless.

The Federal Reserve is expected to start increasing its policy rate later this year, but some other major central banks are continuing to ease policy. Hence, global financial conditions remain very accommodative. Despite fluctuations in markets associated with the respective developments in China and Greece, long-term borrowing rates for most sovereigns and creditworthy private borrowers remain remarkably low.

In Australia, the available information suggests that the economy has continued to grow. While the rate of growth has been somewhat below longer-term averages, it has been associated with somewhat stronger growth of employment and a steady rate of unemployment over the past year. Overall, the economy is likely to be operating with a degree of spare capacity for some time yet. Recent information confirms that domestic inflationary pressures have been contained. That should remain the case for some time, given the very slow growth in labour costs. Inflation is thus forecast to remain consistent with the target over the next one to two years, even with a lower exchange rate.

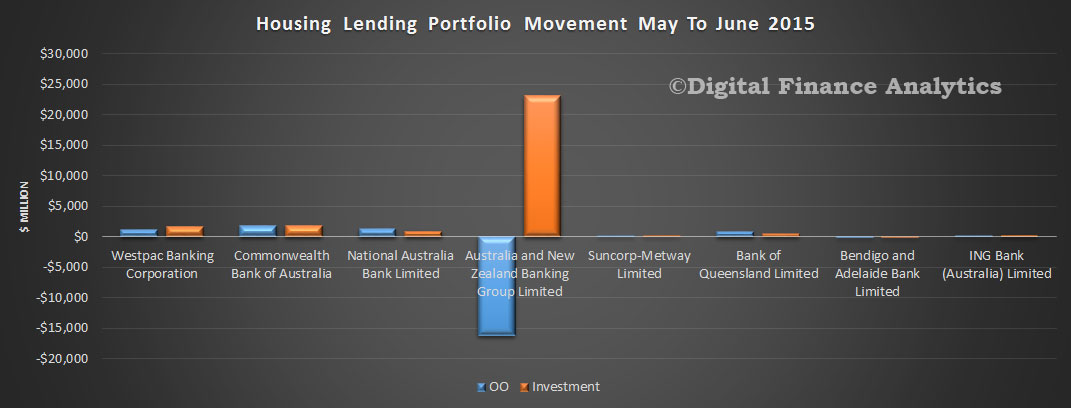

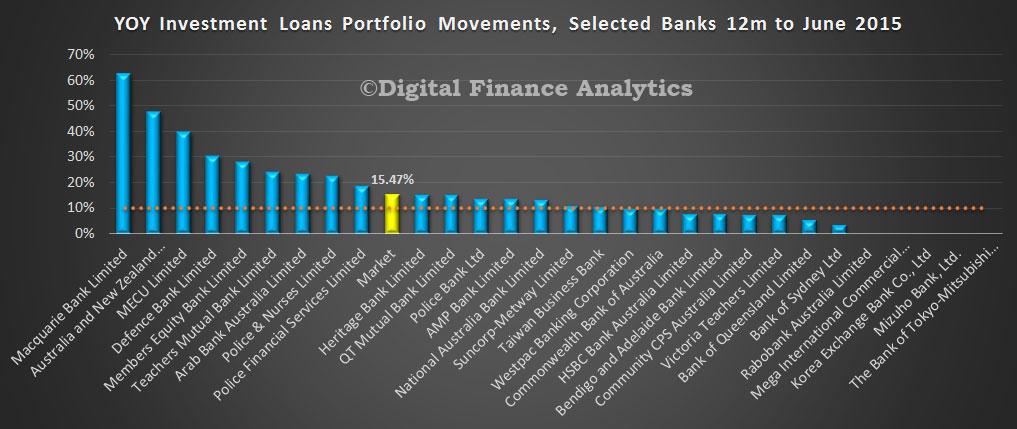

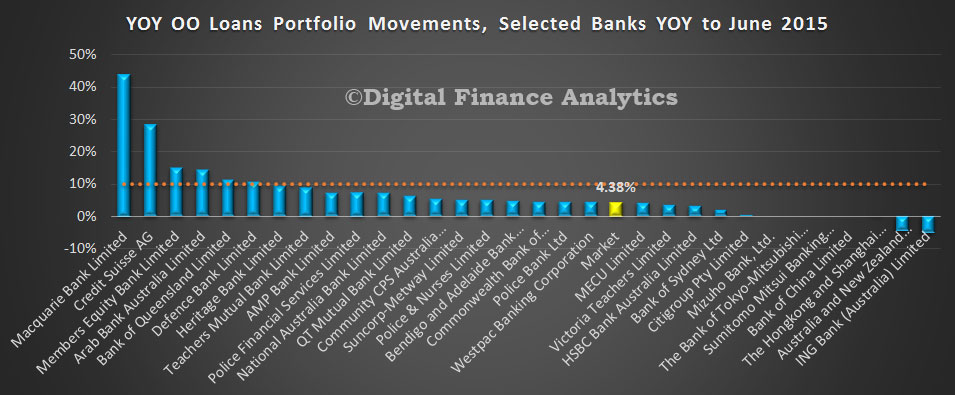

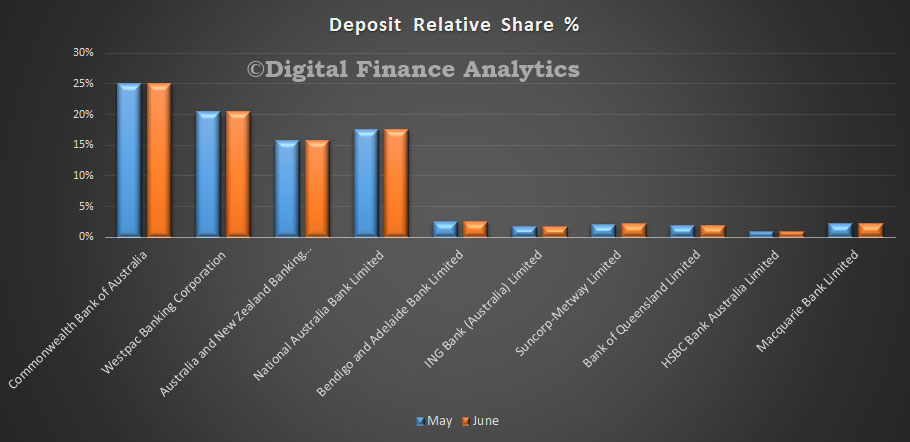

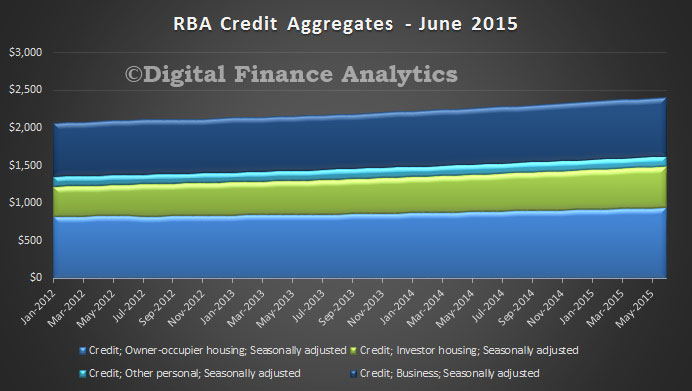

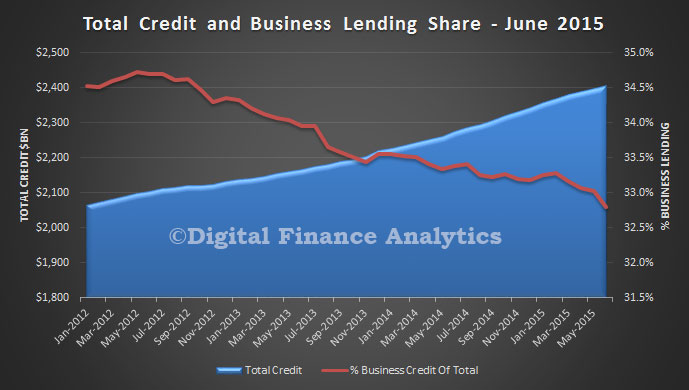

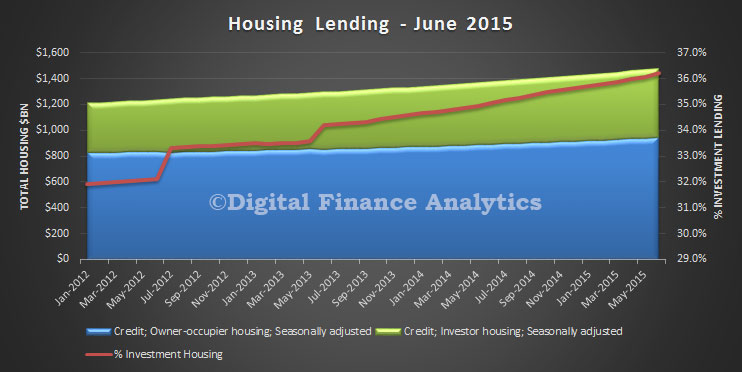

In such circumstances, monetary policy needs to be accommodative. Low interest rates are acting to support borrowing and spending. Credit is recording moderate growth overall, with growth in lending to the housing market broadly steady over recent months. Dwelling prices continue to rise strongly in Sydney, though trends have been more varied in a number of other cities. The Bank is working with other regulators to assess and contain risks that may arise from the housing market. In other asset markets, prices for equities and commercial property have been supported by lower long-term interest rates. The Australian dollar is adjusting to the significant declines in key commodity prices.

The Board today judged that leaving the cash rate unchanged was appropriate at this meeting. Further information on economic and financial conditions to be received over the period ahead will inform the Board’s ongoing assessment of the outlook and hence whether the current stance of policy will most effectively foster sustainable growth and inflation consistent with the target.