ASIC today released a report Payday lenders and the new small amount lending provisions that found that payday lenders need to improve compliance with some of the key consumer protection laws operating in the industry. As at December 2014 there were approximately 1,136 Australian credit licensees that identified that they operate in the payday lending industry (out of a total of 5,842 Australian credit licensees). This figure has declined slightly (by about 6%) over the last 12 months.

Nine of the 13 payday lenders in the review have also diversified their business since the new cap-on-costs provisions commenced. Other business interests and products offered identified in the review include:

- medium amount loans;

- other credit contracts;

- cheque cashing;

- gold buying;

- purchasing delinquent debts;

- secured loans; and

- pawnbroking.

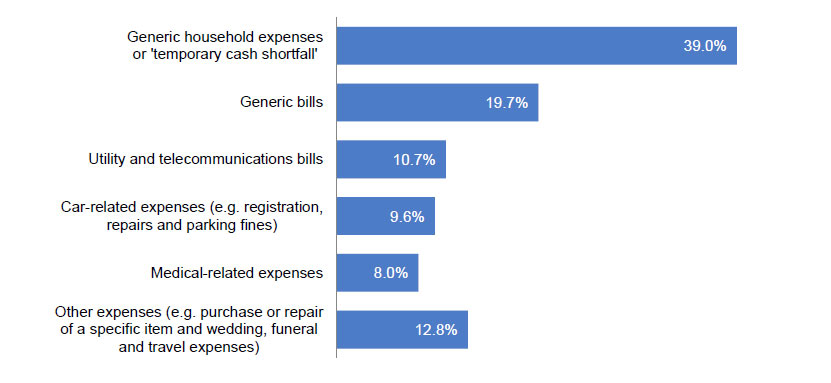

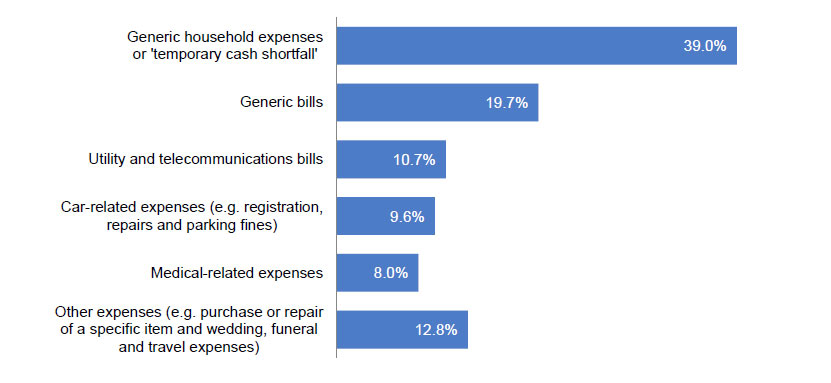

ASIC’s review of 288 consumer files for 13 payday lenders – who are responsible for more than 75 per cent of payday loans made to consumers in Australia – found some lenders engaging in conduct that risks breaching responsible lending obligations. 187 recorded the consumer’s purpose for the loan.

While ASIC’s review found compliance with some rules was working, it also found that payday lenders are falling short in meeting important new obligations introduced as part of the small amount lending reforms in 2013.

While ASIC’s review found compliance with some rules was working, it also found that payday lenders are falling short in meeting important new obligations introduced as part of the small amount lending reforms in 2013.

ASIC’s review found particular compliance risks around the tests for loan suitability, which must be considered when the consumer has multiple other payday loans or is in default under a payday loan.

The review also identified concerns where payday lenders set their loan terms at 12 months or more, thereby charging the consumer more fees, in circumstances where a consumer had requested a shorter term and paid the loan back in that shorter time.

The report also found systemic weaknesses in documentation and record keeping, including around the issue of the consumer’s objectives and needs.

ASIC’s review found better levels of compliance with some regulations, including the requirement to provide a warning about alternative credit options and the income protection rules for Centrelink recipients.

ASIC’s review follows a series of enforcement actions against payday lenders, including the recent Cash Store decision which saw penalties of almost $19 million handed down by the Federal Court for irresponsible lending and unconscionable conduct.

Following the work and the conduct that has been uncovered ASIC has commenced investigations and further follow-up work in certain cases, and will consider enforcement action or other regulatory action.

ASIC became the national credit regulator in 2010. Tighter consumer credit rules for small amount lending were introduced in 2013.

ASIC has focused on three areas of misconduct in the payday lending sector:

- irresponsible lending

- avoidance through business models that attempt to circumvent the law, and

- unfair fees and misleading advertising.

Since 2010, ASIC enforcement action has resulted in close to $2 million in refunds to more than 10,000 consumers who have been overcharged when taking out a payday loan. Payday lenders have also been issued with 13 infringement notices totalling approximately $120,000 in response to ASIC concerns about their compliance with the credit laws.

ASIC notes the 2013 small amount credit reforms will be independently reviewed after 1 July 2015. ASIC will continue its focus on enforcing the current provisions and raising industry standards.

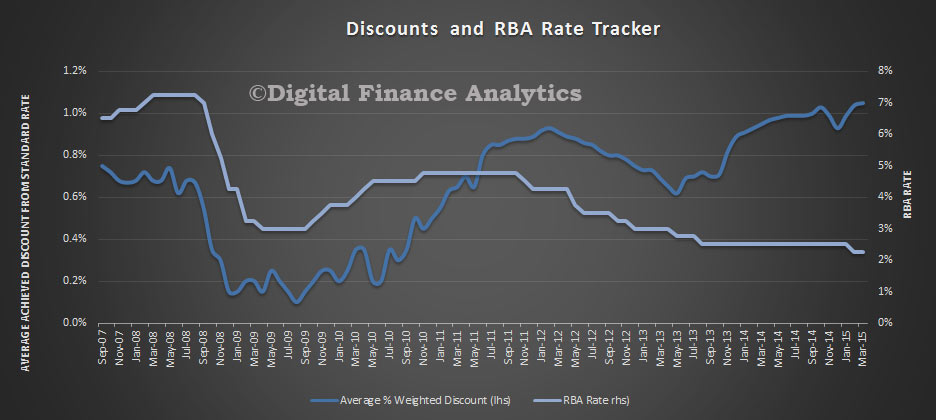

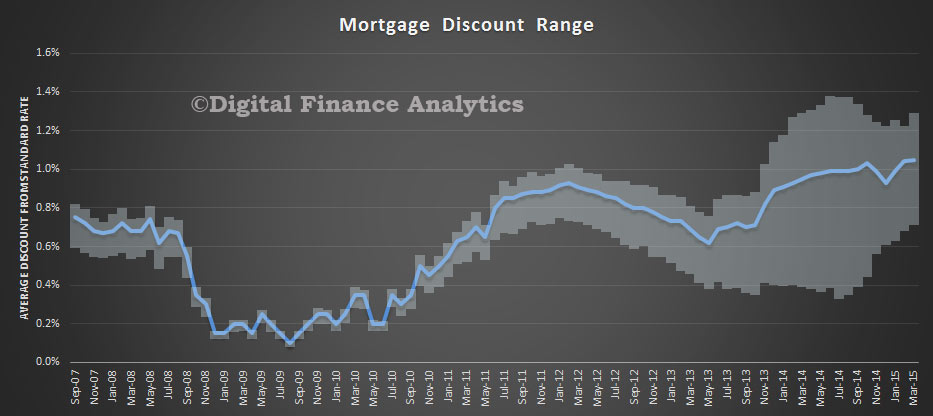

We also see that the range of discounts available are still wide, depending on elements such as customer segment, LVR, loan type, loans size and location. Different players appear to to targeting different business. The best discounts are around 130 basis points.

We also see that the range of discounts available are still wide, depending on elements such as customer segment, LVR, loan type, loans size and location. Different players appear to to targeting different business. The best discounts are around 130 basis points. Our analysis shows that mortgage competition and SME lending is being supported by banks further reducing their returns to depositors. Something which we foreshadowed last year.

Our analysis shows that mortgage competition and SME lending is being supported by banks further reducing their returns to depositors. Something which we foreshadowed last year.