First let me thank CEDA for being our host, once again, as we release the Final Report of the Financial System Inquiry.

I’d also like to recognise some important people.

- My fellow Committee members Kevin Davis, Craig Dunn, Carolyn Hewson and Brian McNamee, all of whom have put in an amazing effort to produce a set of expert judgements shared by us all.

- The International Panel, Michael Hintze, David Morgan, Jennifer Nason and Andrew Sheng.

- The Secretariat, as named in the Report, led very ably by John Lonsdale.

- All of those who have made submissions or otherwise taken an interest in our work.

The Inquiry has been conducted in an open manner. We have consulted extensively with industry participants and end users.

The first round of consultation yielded more than 280 submissions and the second over 6,500. Our Interim Report provided a comprehensive review of Australia’s financial system.

The final report is a shorter and more focused document. It makes 44 recommendations to improve the efficiency, resilience and fairness of Australia’s financial system. It also sets out a blueprint to guide policy making over the next 10 to 20 years and makes 13 observations on taxation for reference to the Government’s Tax White Paper.

The Inquiry’s terms of reference required us to examine how Australia’s financial system can be positioned to support economic growth and meet the needs of end users. We were also asked to consider how the system has changed since the Wallis Inquiry, including the effects of the Global Financial Crisis.

This has not been an Inquiry established to deliver or prevent a particular outcome. Rather it has been conducted as a genuine exercise to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the Australian financial system.

We have considered the financial system in the context of Australia’s economy, particularly our status as a smaller, wealthy, open commodity exporter and described the features of a good financial system from Australia’s perspective.

In formulating our recommendations, we have focused on the national interest and the needs of end users. Our report is evidence-based and wherever possible presents cost/benefit trade-offs in support of our findings.

My purpose today is to explain how our recommendations will adapt the financial system to meet Australia’s special circumstances in the interests of its users and the nation as a whole.

I will first address recommendations that flow from two paradigm shifts since the Wallis Inquiry, namely those relating to resilience and consumer outcomes. Then I will deal with our unique and rapidly growing superannuation system. Lastly, I will talk about competition, efficiency, innovation and regulatory improvement.

While many of the Wallis Inquiry recommendations have stood the test of time, there are two areas where this Inquiry has formed a different view.

First, we believe external shocks can and will occur. As a result of the crisis, governments are now assumed to be the backstop the financial system. In contrast to Wallis, we cannot simply rule out the possibility that the Government will be required to backstop the banks in the event of a crisis. However we believe the system should be managed such that taxpayers are highly unlikely to lose money. We have to take practical steps to reduce moral hazard.

Second, we believe that effective disclosure and financial literacy are necessary but incomplete approaches for delivering satisfactory consumer outcomes. For this reason, we have highlighted the need for improved firm culture along with stronger obligations in some areas, especially in product manufacture and distribution.

The Inquiry makes six recommendations which directly address the issue of resilience, and two relating to competition and superannuation which also have consequences for system resilience.

I will discuss competition in the residential mortgage market later.

In relation to capital, the Inquiry believes the capital ratios of Australian banks should be ‘unquestionably strong’. Specifically, they should be ranked in the top 25 per cent of global banks. The major banks are currently somewhere between the global median and the 75th percentile. This means that they are not ‘unquestionably strong’. Accordingly, they should be required to increase their capital ratios so that they are in the top 25 per cent of global peers, and a process for more transparent reporting of comparative capital ratios should be developed.

Also in relation to capital, we recommend the Government should proceed to introduce a leverage ratio as a backstop to ADI’s risk weighted capital positions – in line with the unfinished Basel III agenda.

Proposals for the issuance of ‘bail-in’ debt securities should, however, not move ahead of developing international standards. If issued, this form of debt should conform to the principles relating to legal certainty outlined in our Report. We do not propose that depositors should be bailed-in.

The Report also endorses existing processes to improve pre-positioning, crisis management and resolution powers for regulators.

The Financial Claims Scheme should continue to be funded on an ex post basis, partly because our recommendations on resilience reduce the need for an ex ante levy.

To limit systemic risk and in the interests of fund members, we have recommended a general prohibition on direct borrowing for superannuation funds.

Generally, higher capital ratios and loss absorbency represent a form of insurance. They reduce both the likelihood and cost of failure. The Inquiry believes that the cost of this insurance is low and is significantly outweighed by the benefits of a more resilient system.

The Inquiry has been conducted against the backdrop of ongoing concerns about the quality of financial advice; a parliamentary inquiry into ASIC’s performance; and debate over amendments to the regulatory framework governing advice.

However, it would be a mistake to look at our recommendations in this area only through the narrow lens of the recent debate on FOFA.

Our six recommendations are based on a much broader assessment of the current framework, of which FOFA is only a small component.

We have identified three problems with the current arrangements.

First, firms do not take enough responsibility themselves for treating consumers fairly. This places pressure on the regulatory framework and the regulator.

Secondly, the current framework places too much reliance on disclosure and financial literacy. While these are important, they are not sufficient to deliver appropriate consumer outcomes.

Thirdly, we need a more pro-active regulator but, to be clear regulation cannot be expected to prevent all consumer losses. Our recommendations are not meant to absolve consumers of responsibility for their choices or insulate them from market risk; rather they are intended to reduce the risk of consumers being sold poor quality or unsuitable products.

Consistent with the approach in other industries where information imbalances can cause significant consumer detriment, product manufacturers should be required to consider the suitability of their products for different types of consumers as part of the design process.

Hence we have recommended the introduction of a targeted and principles-based product design and distribution obligation.

We also believe there needs to be a change in the approach of the regulator. ASIC should be a stronger and more proactive regulator that undertakes more intense industry surveillance and responds more strongly to misconduct once identified. Numerous submissions claimed it is under-resourced. We have recommended an industry funding model for ASIC.

We are putting the individual at the centre of the superannuation system and strengthening its focus on retirement incomes, because we believe the provision of income in retirement should be enshrined as the system’s primary objective.

The Inquiry has identified two major issues with the superannuation system.

Fees are too high in the accumulation stage given the substantial growth we have seen in fund size and member balances. And superannuation assets are not being converted into retirement incomes as efficiently as they could be.

The absence of strong consumer driven competition remains a significant problem in the accumulation phase. MySuper aims to improve efficiency and competition by mandating simple low cost default products and by encouraging funds to become larger. It has only been in place for around 18 months. However, we are not confident it will drive the efficiency improvements required. We have therefore laid down a challenge to the superannuation industry.

We have recommended a review of MySuper by 2020 to assess whether or not it has delivered sufficient improvements in competition and efficiency. If it has not been effective, we recommend the Government introduce a competitive mechanism under which only the best performing funds would be selected to receive default superannuation contributions. This would allow all default members to benefit from the type of purchasing power that currently delivers lower fees to employees of large firms that have negotiated bulk discounts for their employees.

The retirement phase of Australia’s superannuation system is under-developed.

Members need more efficient retirement products that better meet their needs and increase their capacity to manage longevity risk.

We therefore recommend that all fund members should be offered what we have called a Comprehensive Income Product for Retirement when they switch from accumulation to retirement. This would combine an account based pension with a pooled longevity risk product.

Retirees would benefit from these products because they would have higher incomes and would not be exposed to the risk of outliving their savings.

The trade-off would be that less money saved through superannuation would be available for bequests, reflecting our view that the system should be about retirement incomes.

Collectively, the Inquiry’s superannuation recommendations have the potential to increase retirement incomes for an average male wage earner by around 25 to 40 per cent, excluding the Age Pension.

Competition is the cornerstone of a well-functioning financial system, driving efficient outcomes for price, quality and innovation. Some parts of the system have experienced increased market concentration, especially in the wake of the financial crisis. Our aim has been to ensure there will be an adequate focus on competition in the future.

In the residential mortgage market we have recommended narrowing the gap between IRB and standardised model risk weights for housing loans by increasing the former to between 25 and 30 per cent. This corresponds with a small funding cost increase for the major banks. However, competition will limit the extent to which these costs are passed on to consumers.

In some industries, competition has not resulted in reasonable prices for card transactions. The largest number of submissions we received related to customer surcharging for credit card transactions. We have recommended the Reserve Bank should ban surcharging for low cost cards and cap surcharges in relation to credit cards. This should address concerns about excessive surcharging in some industries.

More than a quarter of our recommendations are designed to enhance competition. For example, we have recommended giving ASIC a competition mandate; three-yearly external reviews of competition in the financial sector; and regulation that is more technologically neutral to facilitate full on-line service delivery.

To facilitate continued innovation in the financial system, we have emphasised the need for regulatory frameworks to be more flexible and adaptable. Graduated frameworks are important to ensure that new entrants are not over-regulated and to provide scope for innovation.

We have made several recommendations to reduce structural impediments to SME access to credit and facilitate innovation in this area. Our focus has been on boosting competition, for example by encouraging the emergence of rival lenders and new techniques such as crowdfunding and peer-to-peer lending. Some of these recommendations will also assist development of the venture capital market. We have also identified issues with the fairness of SME loan contracts in relation to non-monetary default clauses.

Our emphasis on competition is designed to create a more efficient system. In considering allocative and dynamic efficiency, we have identified several aspects of Australia’s tax settings that distort the flow of funds, especially differential treatment of savings vehicles and barriers to cross-border capital flows. Because our terms of reference do not allow us to make recommendations on tax, these observations will flow into the Government’s Tax White Paper. The Report also addresses issues relating to the corporate bond market.

The regulatory architecture developed after the Wallis Inquiry is reasonably effective. Our recommendations aim to build on the current arrangements. We want regulators that are strong, independent and accountable. Our recommendation for a Financial Regulation Accountability Board will ensure our financial regulators are subject to regular systematic scrutiny and instil a culture of continuous improvement.

In approaching our task, the Committee has emphasised Australia’s need for a high quality financial system, setting out the roles and responsibilities of its participants.

The unique characteristics of Australia’s economy demand high quality in the eyes of the world because we want to continue to be successful at augmenting our own savings with foreigners’ savings to develop the economy.

We have a good track record at this and a generally reliable system of law and public administration. However, as a commodity driven economy we experience higher cyclical volatility in national income and we have very high net foreign liabilities at more than half our GDP. These factors cause the rest of the world to monitor closely the quality of our settings.

The Report assesses the potential costs of serious disruption to the financial system. The Basel Committee has estimated the average total cost of a financial crisis at around 63 per cent of a country’s annual GDP. For Australia, this is $950 billion, with 900,000 additional Australians out of work. The economic cost of a severe crisis is much higher – around 158 per cent of annual GDP. For Australia, this is around $2.4 trillion. And this is just the annual cost.

Our experience during the Global Financial Crisis makes it very difficult for Australians to empathise with the depth of the economic and social loss in other countries. Yet the circumstances that shielded Australia from the crisis will not recur.

We had very high terms of trade, negligible net government debt, a Budget surplus, a triple A credit rating, a record mining investment boom, and a major trading partner growing in real terms at an annual rate of around 10 per cent and able to throw immense resources at a stimulus program that favoured our exports.

For all these reasons we need to maintain credibility among foreign investors and have an unquestionably strong banking system. The marginal cost of achieving this is small relative to the economic and social cost to the country and to taxpayers when a crisis occurs in less favourable circumstances than the last one.

We also need to ensure the Government maintains a strong fiscal position. The crisis demonstrated how quickly government finances can deteriorate and how damaging this can be for the relevant country. Deterioration in the Government’s credit rating would have a direct effect on the cost of credit in the system.

We have designed our report and its recommendations to put Australia’s financial system in the very highest quality position. My colleagues and I simply ask that you embrace our recommendations in the national interest.

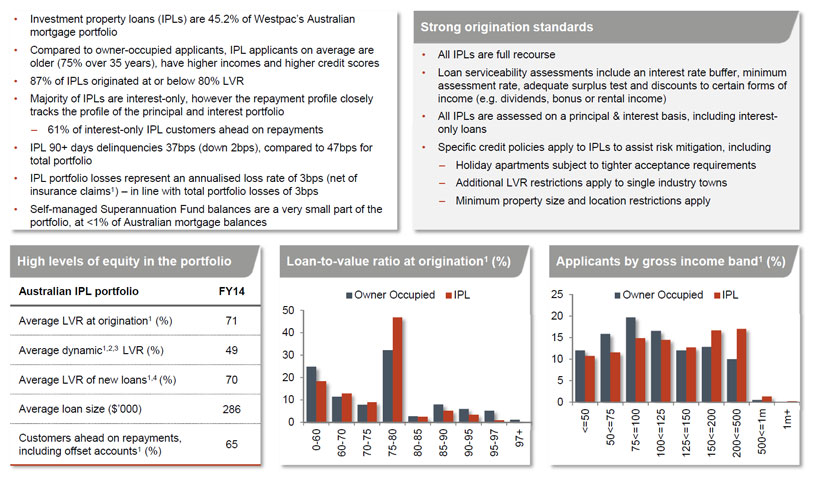

Other banks have different underwriting formulations with buffers of between 1.5% and 2.25% buffers. ASIC has of course also stressed that lenders must consider borrowers ability to repay and take account other expenditure. There is evidence of the “quiet word from the regulator” working as recently we have noted some slowing investment lending at WBC (currently they would be below the 10% threshold) and amongst some other lenders too. However, some of the smaller lenders may be impacted by APRA guidance, given stronger recent growth.

Other banks have different underwriting formulations with buffers of between 1.5% and 2.25% buffers. ASIC has of course also stressed that lenders must consider borrowers ability to repay and take account other expenditure. There is evidence of the “quiet word from the regulator” working as recently we have noted some slowing investment lending at WBC (currently they would be below the 10% threshold) and amongst some other lenders too. However, some of the smaller lenders may be impacted by APRA guidance, given stronger recent growth.