Recent price rises (close to A$18,000 in the past three months) may be too great and can’t continue. But the Bitcoin market is only just maturing as an investment and as a currency, and so it may still have room to grow.

A bubble is when the price of an asset diverges from its “fundamentals” – the aspects of an asset that investors use to value it. These could be the income that can be earned from a stock over time, a company’s cash flow, the state of a country’s economy, or even the rent from property.

But Bitcoin does not pay out profits (like shares) or rent (like property), and is not attached a national economy (like fiat currencies). This is part of the reason why it is hard to tell what the underlying value of Bitcoin is or should be.

In the search for fundamentals some have suggested we should look at the supply of Bitcoins in the market (which is regulated by the technology itself), the number of Bitcoin transactions through the market, or even the energy consumed by Bitcoin miners (the computers that validate transactions and are rewarded with Bitcoins).

Diverging from fundamentals

If we take a close look, we can see how the price of Bitcoin may be diverging from these fundamentals. For instance, it is becoming less profitable to be a miner, especially as the energy required increases. At some stage the cost may exceed the price of Bitcoin, making the network less worthwhile to both mine and invest.

Bitcoin may be the best known cryptocurrency but it is also losing marketshare to other cryptocurrencies, such as Ethereum and Litecoin. Bitcoin currently accounts for 59.4% of the total global cryptocurrency market, but at the beginning of 2016 it was 91.3%. Many of these other cryptocurrencies have more functionality than Bitcoin (such as Ethereum’s ability to execute smart contracts), or are more efficient and use less energy (such as Litecoin).

Government policy, such as taxation or the establishment of national digital currencies, may also make it riskier or less worthwhile to mine, transact or hold the cryptocurrency. China’s ban on Initial Coin Offerings earlier this year reduced the value of Bitcoin by 20% in 24 hours.

Without these fundamentals the price of Bitcoin largely reflects speculation. And there is some evidence that people are simply buying and holding Bitcoin in the hope it will keep rising in value (also known as Greater Fool investing). Certainly, the cap on the total number (21 million) of Bitcoins that can exist, makes the currency inherently deflationary – the value of the currency relative to goods and services will keep increasing even without speculation and so there is a disincentive to spend it.

Bitcoin still has room to grow

Many big investors – including banks and hedge funds – have not yet entered into the market. The volatility and lack of regulation around Bitcoin are two reasons stopping these investors from jumping in.

There are new financial products being developed, such as futures contracts, that may reduce the risk of holding Bitcoin and allow these institutional investors to get in.

But Bitcoin futures contracts – where people can place bets on the future price of stocks or markets – may also work against the price of Bitcoin. Just like gamblers place bets on horse races rather than buying a horse, investors may simply buy and sell the futures contracts rather than Bitcoin itself (some contracts are even settled in cash, rather than Bitcoin). All of this could lead to less actual Bitcoin changing hands, leading to less demand.

Although the rush to invest is apparently encouraging some people to take out mortgages to buy Bitcoin, traditional banks won’t lend specifically for that purpose as the market is too volatile.

But it’s not just on the finance side that the Bitcoin market is set to expand. More infrastructure to support Bitcoin in the broader economy is rolling out, which should spur demand.

Bitcoin ATMs are being installed in many countries, including Australia. Bitcoin lending is emerging on peer-to-peer platforms, and new and more regulated marketplaces are being created.

Many companies are accepting Bitcoin as payment. That means that even if the speculation dies down, Bitcoin can still be traded for some goods and services.

And finally, although the fundamentals of Bitcoin are still up for debate, when it comes to transaction volume through the network there appears to be a lot of room for growth.

It’s good to remember that people have been calling Bitcoin a bubble for a long time, even when the price was just US$35 in 2013.

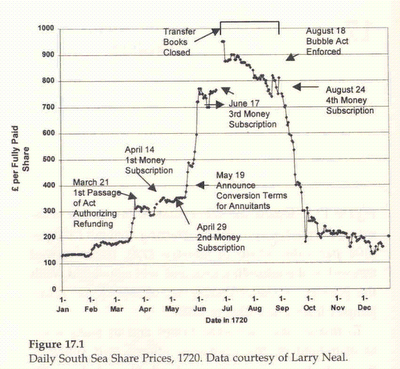

In the end, this is uncharted territory. We don’t know how to value Bitcoin, or what will happen. Historical examples may or may not apply.

What we do know is that the technology behind most cryptocurrencies is enabling new models of value transfer through secure global consensus networks, and that is causing excitement and nervousness. Investors should beware.