High Frequency Trading is an arms race in the quest for speed. It creates an ever more uneven playing field. This article from Zero Hedge demonstrates to what lengths the high frequency traders will go for just a few millisecond advantage – which makes in the HFT world makes all the different between billions in profits and losses – Bloomberg reports that a mysterious antenna has emerged in an empty field in Aurora, near Chicago, and a trading fortune depends on it.

Strange? Of course: as BBG’s Brian Louis admits “it was an odd transaction from the outset: $14 million, double the going rate, for a 31-acre plot of flat, undeveloped land just west of Chicago. In the nine months since, the curious use of the space has only added to the intrigue. A single, nondescript pole with two antennas was erected by a row of shrubs. Some supporting equipment was rolled in. That’s it.”

Strange? Of course: as BBG’s Brian Louis admits “it was an odd transaction from the outset: $14 million, double the going rate, for a 31-acre plot of flat, undeveloped land just west of Chicago. In the nine months since, the curious use of the space has only added to the intrigue. A single, nondescript pole with two antennas was erected by a row of shrubs. Some supporting equipment was rolled in. That’s it.”

As it turns out, those antennas – as readers may imagine – were anything but ordinary. Same goes for the buyer of the property: anything but your typical land investor, although the name will be all too familiar to those who have followed our reporting on HFT over the years: it was Jump Trading LLC, “a legendary and secretive trading firm that’s a major player in some of the most important financial markets.”

Equipment on land purchased by an affiliate of Jump Trading

Equipment on land purchased by an affiliate of Jump Trading

Jump Trading affiliate World Class Wireless purchased the 31-acre lot for $14 million, according to county records. “They paid probably twice as much as it’s worth,” said David Friedlandof Cushman & Wakefield. “I don’t see anyone else paying close to that price.”

There was a reason why Jump overpaid so much: it was an investment into guaranteed future returns.

Because ultimately the purchase was all about the location: just across the street lies the data center for CME Group, the world’s biggest futures exchange. By placing its antennas so close to CME’s servers, Jump hopes to shave maybe a microsecond off its reaction time, enough to separate a winning from a losing bid in trading that takes place at almost the speed of light. Enough to make billions in profits if done successfully millions of times every minute for year.

As Bloomberg describes the land grab, “it was the latest, and perhaps boldest, salvo in an escalating war that’s being waged to stay competitive in the high-speed trading business.”

The war is one of proximity — to see who can get data in and out of CME the quickest. A company called McKay Brothers LLC recently won approval to build the tallest microwave tower in the area while another, Webline Holdings LLC, has installed microwave dishes on a utility pole just outside the data center.

“It tells you how valuable being just a little bit faster is,” said Michael Goldstein, a finance professor at Babson College in Babson Park, Massachusetts. “People say seconds matter. This is microseconds matter.”

It also tells you something else: at its core, modern trading is simply about being faster than your competition: no thinking goes into the trade, only reaction times matter. That, and frontrunning your competition. Some more details about this literal land grab:

In October 2015, McKay Brothers, a company that sells access to its microwave network to high-speed traders, leased land diagonal to the CME data center, under the name Pierce Broadband LLC, according to DuPage County property records.

Last month, the county gave McKay approval to erect a 350-foot high microwave tower that could be 600 feet closer to the data center than its current location, records show. Two trading firms, IMC BV and Tower Research Capital LLC, own minority stakes in McKay. Co-founder Stephane Tyc said his firm may never build the tower but it would be part of the firm’s continual efforts to speed transmission time.

Then there’s Webline Holdings. In November 2015, it was granted a license to operate microwave equipment on a utility pole just outside the data center, according to Federal Communications Commission records. Webline has licenses for a microwave network stretching from Aurora to Carteret, New Jersey, where Nasdaq Inc.’s data center is located. Messages left for Webline were not returned.

Back to the mysterious antenna: according to Bloomberg, the license for the transmission dishes is held by a joint venture between World Class and a unit of KCG Holdings, another HFT trading firm that was recently acquired by Virtu Financial. In other words, the “who is who” of HFT has been unleashed on an empty field near Chicago, and to the builder will go the spoils. It could be billions in revenues.

After all this frentic building of microwave tower, who is closest to the CME servers? It is unclear. Trading data first leaves CME computers via fiber cable, and then to nearby antennas that send it by microwave to other towers until it reaches New Jersey, where all the major U.S. stock exchanges house their computers. The moves in Aurora are intended to reduce the time that the data is conveyed through cable; the practical impact is shaving off a millisecond or maybe even a few nanoseconds.

At its core, the race is about latency arbitrage, and not being the slowest firm on the block – a recipe for financial ruin. Sending data back and forth between the U.S. Midwest and East Coast allows high-frequency traders to profit from price differences for related assets, including S&P 500 Index futures in Illinois and stock prices in New Jersey. Those arbitrage opportunities often last only tiny fractions of a second.

Ironically, all the land grab and overpriced land purchases could be made obsolete with one simple decision: a microwave tower could be installed on the roof of the CME data center to eliminate the need for jockeying around the site, the same way the NYSE has a microwave tower next to its NJ headquarters. The exchange is indeed looking at allowing roof access, along with CyrusOne, the company that bought the data center last year, CME said in a statement. Traders being traders, however, they may continue to battle, this time for the most advantageous position on the microwave tower itself.

“We are confident the CME can provide an alternate and better solution which offers a level playing field to all participants,” said McKay’s Tyc.

Which is ironic because at its core, modern High Frequency Trade is about everything but a level playing field: after all there are millions of traders to be frontrun, take that away, and the HFT parasites of the world have no advantage whatsoever.

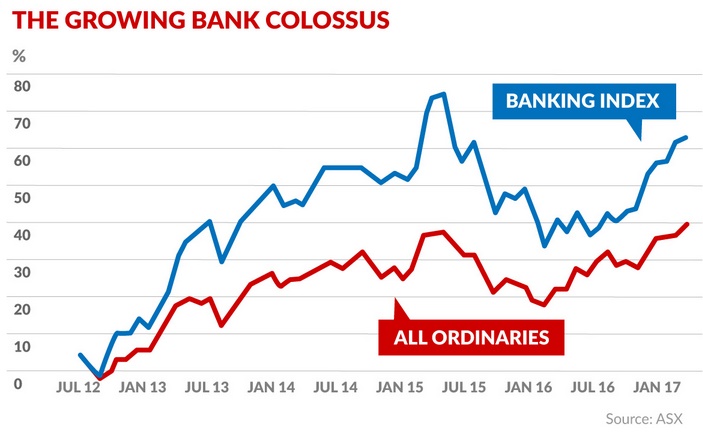

A range of factors are in play, including the bank tax, rising concerns about the banks exposure to property, and the risks of higher defaults in a low growth higher risk environment.

A range of factors are in play, including the bank tax, rising concerns about the banks exposure to property, and the risks of higher defaults in a low growth higher risk environment.

Equipment on land purchased by an affiliate of Jump Trading

Equipment on land purchased by an affiliate of Jump Trading