Andrew Bailey, Deputy Governor, Prudential Regulation and Chief Executive Officer, Prudential Regulation Authority gave a speech at Cambridge University – Financial Markets: identifying risks and appropriate responses – which discusses important concepts in relation to the effective supervision of Financial Markets, in the context of expanding bond markets and automated electronic trading. There is good evidence that financial market conditions have evolved in ways that reduce the likelihood of continuous market liquidity in all states

There is a commonly-held narrative about the financial crisis that the banks caused it, and the solution is more regulation of both an economy-wide (macro-prudential in the jargon) and firm specific (micro-prudential) type. But it isn’t that simple, and tonight I want to outline the role of financial markets and non-bank institutions (which sometimes go under the somewhat pejorative term of shadow banks ) within the overall financial system and describe how, with sufficient resilience, they play a number of key roles in the financial system, including offering borrowers alternatives to bank lending. Nevertheless, I also want to explain why there is significant and increasing emphasis on the risks they can pose to financial stability. Put simply, it is quite often said that we are living in unprecedented times in the performance of financial markets.

The simple narrative around banks is that they over-extended themselves (over-leveraged in terms of the ratio of assets to capital and over-extended in terms of the ratio of illiquid to liquid assets) in the run-up to the crisis, and the resulting problems had two closely linked and malign effects: first, the crisis jeopardised the provision of those core financial services which banks provide and on which all of us depend; and second, by so doing – and being too big or complicated to deal with as failed companies – they required the use of taxpayers’ money to bail them out. That’s the story, and it explains why the public policy actions taken both immediately after the crisis (bail-outs) and the subsequent post-crisis reforms have been directed at protecting those or core financial services and seeking to ensure that taxpayers’ money does not need to be put at risk.

There is however more to the story than that. In the period between the early 1990s and the onset of the crisis, there was a remarkable and unprecedented evolution of the financial system which involved a major expansion of activity. Banks moved from a traditional model of taking deposits and lending them out, to a model that involved far more the origination and distribution of loans – often known often as securitisation, in which these loans were substantially distributed to shadow banks. These shadow banks thereby took on more of the traditional core bank functions of credit assessment and maturity transformation (the practice of borrowing at shorter maturities than the maturities of the assets they held). And, they did so, like the banks, with weak levels of capital.

But, it would be a mistake to portray shadow banks as bad. There is good evidence that in the twenty years before the crisis they emerged as a stabilising force (most notably in the US) because they were able to expand their provision of credit at times when traditional bank lending underwent cyclical contractions. That said, there were some troubling properties associated with the growth of shadow banking. For instance, quite a few were sponsored by banks as a means to reduce the amount of capital to be held against risk exposures. When the crisis hit, in a number of cases those banks found they had to stand behind their offshoots for contractual or reputational reasons, so the separation was illusory and led to greater leverage in the system. Another issue was that the originate and distribute model of securitisation was often opaque and led to insufficient genuine risk transfer away from the banking system, in ways that became very problematic when the crisis hit. Shadow banks, also neglected the funding side of their balance sheets, so that they came to depend upon using their assets as security to obtain funding, often from banks. This is quite different from the traditional model of deposit funded banking where the assets (loans) are not used as security for raising funds. However, it must be said that in the run-up to the crisis, banks too came to depend overly on such secured funding. When the crisis hit, the value of the assets used as security for collateral fell, funding conditions tightened and in some instances were cut off .

These weaknesses meant that the counterbalancing behaviour of shadow banks vanished. Instead, they retracted just as banks did, but much more violently, which exacerbated the magnitude of the crisis. The result was therefore greater volatility in financial markets, and a dramatic increase in the vulnerability of economies to financial shocks. This contraction in credit supply was thus a powerful channel through which the financial sector hit economies. The result was the largest contraction in real economic activity since the Great Depression. In the better times, securitisation and the shadow banking system appeared to have reduced the sensitivity of the aggregate supply of lending and thus the sensitivity of the real economy to transitions in bank funding conditions. But they did not do so at the point it would have been most valuable, during the global crisis. As Stanley Fischer has recently put it: “when non-banks pulled back, other parts of the system suffered. When non-banks failed other parts of the system failed.”).

The originate to distribute model created tradeable assets – the securities in securitisation. The success of the model depended on there being liquid secondary markets for these securities. In its broadest sense, market liquidity refers to the ease with which one asset can be traded for another, and thus different markets can be more or less liquid. The level of liquidity in financial markets depends on among other things the amount of arbitrage or market making capacity and whether specialised dealers (market makers) will step in as buyers or sellers in response to temporary imbalances in supply and demand (Fender and Lewrick 2015). In what appeared to be normal times before the crisis, there was abundant capacity to maintain liquidity in markets, supported by banks and shadow banks such as hedge funds.

But during the crisis, such capacity became much more scarce or even undeployed, and market liquidity dried up. The key point here is that the originate to distribute approach depended on continuous liquidity in financial markets, and when that dried up in the crisis the effects were severe.

I want to move on now to what has happened since the crisis. Financial market activity has grown rapidly. There are many statistics that could be quoted, so to choose one, over the last 15 years, global bond markets have grown from around $30 trillion in 2000 to nearly $90 trillion today. That is a lot, not least because in the middle of that 15 year period came the global financial crisis. Therefore, when it comes to the task of maintaining market liquidity, there is a lot more to hold up. Also, the broad investment or asset management sector is now much larger, at around $75 trillion at end-2013. Thus, in the wake of the financial crisis there has been a substantial increase in the intermediation of credit via financial markets rather than long-term on the balance sheets of banks, involving both the supply of new credit to borrowers and the absorption of assets coming out of the banking system, as banks reduce their balance sheets.

Over the same period, there has been a fundamental and rapid change in the microstructure of financial markets – the organisation of how they work. Electronic platforms are increasingly used in a number of major financial markets (notably equity and foreign exchange markets). As part of that change, automated trading – which is a subset of electronic trading using algorithms to determine trading decisions – has become common in those markets. And, within automated trading, there has been growth in high frequency trading – which relies on speed of execution to get ahead of other market players . While electronic trading has contributed to increasing market efficiency and probably reducing transaction costs, there are also risks that arise from trading strategies that are flawed, or where in constructing the strategy not all possible outcomes were considered, including the ability to trade large blocks.

To recap, the last two decades have seen major changes in the financial system. These have, in turn, shaped the impact of the global financial crisis and its aftermath. I want now to look at the aftermath of that crisis and pick out several developments that are important for understanding current and future risks to financial stability.

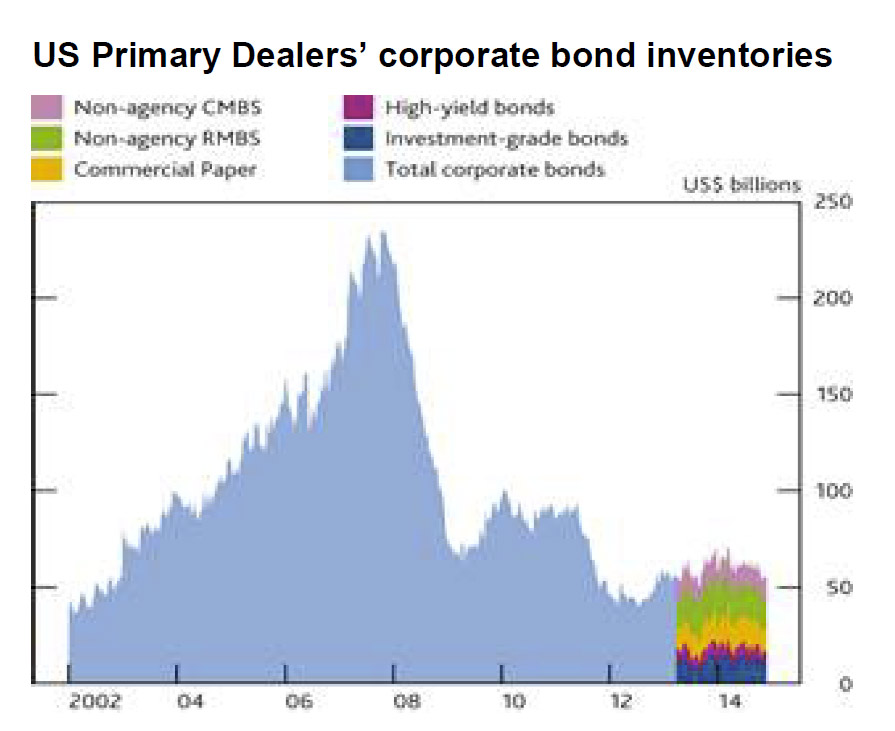

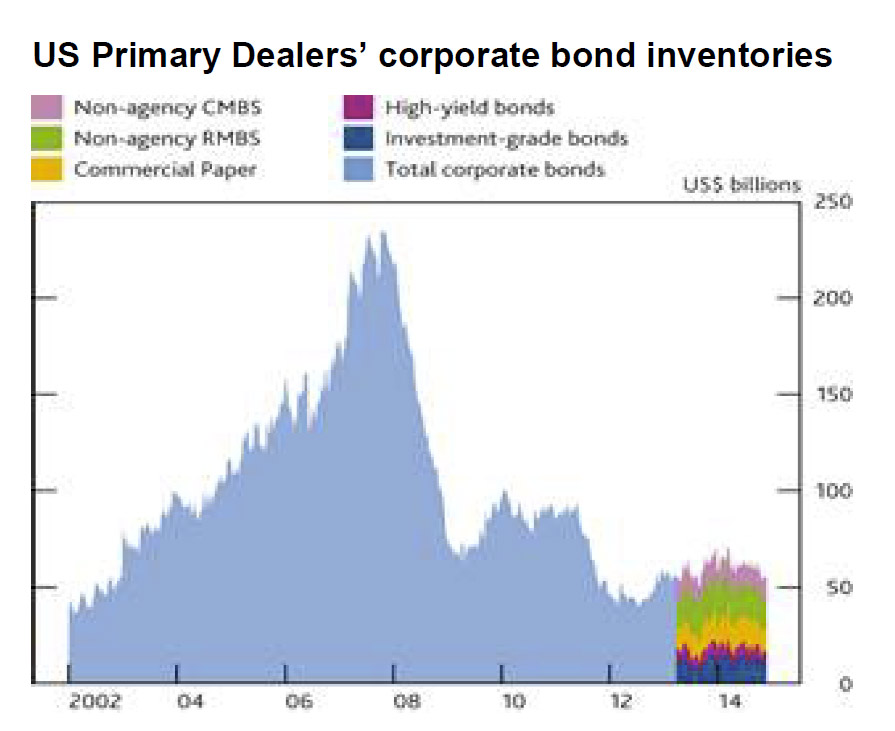

The first development concerns the overall pattern of activity in financial markets. While the size of global bond markets has grown rapidly, the evidence indicates that trading volumes in a number of markets have declined. Bond inventories held by primary dealers have likewise reduced, bid-ask spreads have risen in the corporate bond markets, and it has become more expensive to hedge named credit risk using derivatives. A key point here is that the balance sheets of dealers active in these markets have shrunk markedly, with many fewer firms active in market-making.

Markets have grown, but the capacity to maintain liquidity – as judged by the market–making capacity of the major banks and broker-dealers – has declined . As my colleague Chris Salmon recently put it, this reduction in market making capacity has been associated with increased concentration in many bond markets, as firms have become more discriminating about the markets they make, or the clients they serve. But this trend has gone hand-in-hand with a growth in assets under management, with important implications for the provision of liquidity by market makers in times of stress in those markets.).

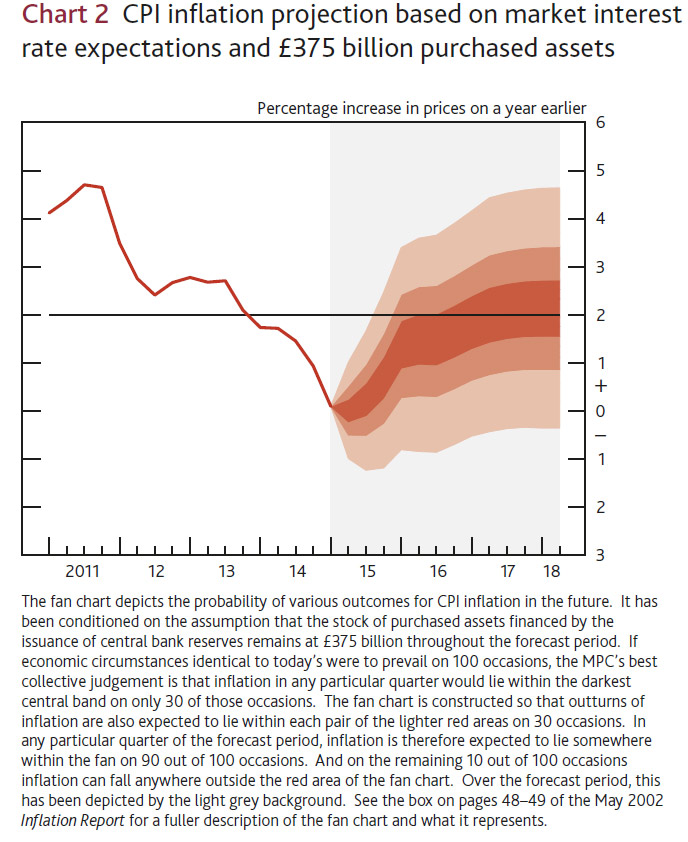

The second post-crisis development is the natural consequence of the severity of the crisis and its impact on real economies. The extraordinary (by historical standards) degree of monetary policy easing by central banks was followed by a fall in volatility in financial markets. Markets appeared to come to take comfort from their own mantra of “low-for-long” rates which in turn incentivised a “search for yield” (to be clear, “low for long” has not been in the phraseology of central banks).

Studies of the US Treasury market have indicated that the Federal Reserve’s programme of Quantitative Easing (QE) caused a reduction in the liquidity premium return for holding those bonds. Part of the effect of QE programmes is to improve market conditions for the targeted asset classes but also to see the trickle down to other asset classes as market conditions change more generally). To be clear however, QE asset purchase operations were not designed to tackle a liquidity problem in the financial system. Rather, the impact on liquidity was one of the channels through which QE has affected the real economy and thus has had its intended effect in monetary policy terms. While estimates of the impact of QE are inherently uncertain, one of the desired outcomes of central bank asset purchases is to lower yields thus affecting longer term interest rates and creating a positive economic effect. In doing so, QE can improve the functioning of financial markets by reducing liquidity premia.

The third post-crisis development is the impact of the growth of automated trading in financial markets, and the challenges this poses for maintaining continuous market and liquidity. Over the last year volatility in many financial markets has picked up from a low base and we have seen some acute but short-lived incidents of extreme volatility and impaired liquidity in secondary markets. On 15 October last year there was unprecedented volatility in the US Treasury market, and on 15 January this year there was substantial volatility in the Swiss Franc exchange rate following the unexpected decision by the Swiss National Bank to remove its Europe/Swiss Franc floor. Now, central banks are known for their powers of understatement, so what do I mean by words like “unprecedented” and “substantial”. On 15 October, 10 year US Treasury yields moved intra-day by around 8 standard deviations of preceding daily changes. On 15 January, the Swiss Franc moved by more than 30 standard deviations. For rough scale, an 8 standard deviation move should happen once every three billion years or so for normally distributed data.

You may at this point recall the saying popularised by Mark Twain, about “lies, damned lies and statistics”. I think I can be reasonably confident in saying that the fact of these events happening does not mean that we should expect low volatility in financial markets for at least the next three billion years.

I am not going to spend time discussing the causes of these events; suffice to say that there was news of an unexpected sort, and the size of the resulting moves points to greater sensitivity in the response of markets. The ability of markets to trade without triggering major price moves was limited. That said, by the end of both days, volatility had reduced, prices had retraced a portion of their peak intra-day moves and liquidity returned. This quick stabilisation helped to limit contagion to other markets, and thus wider effects on the stability of the financial system. Should we therefore be concerned? My answer to that is we should certainly be keenly interested. I agree with the conclusion of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York that understanding the manner in which the evolving market structure is affecting market liquidity, efficiency and pricing is highly important ). This conclusion has been reinforced in the recent publication of the Senior Supervisors Group (SSG) in which the PRA participates). The SSG has concluded that “key supervisory concerns centre on whether the risks associated with algorithmic trading have outpaced control improvements. The extent to which algorithmic trading activity, including HFT, is adequately captured in banks’ risk management frameworks, and whether standard risk management tools are effective for monitoring the risks associated with this activity, are areas of inquiry that all supervisors need to explore”.

As supervisors of almost all of the world’s major trading banks – through their operations in London – we can provide some helpful assessment of these events. We have observed that the balance between aggregate buy and sell orders submitted to banks’ electronic trading systems can shift instantaneously, and sometimes violently, upon this type of occurrence. The impact is often exacerbated by the simultaneous reduction in order book depth on organised multilateral electronic trading venues. The electronic trading contribution was more evident on 15 January, as a foreign currency market event than the 15 October (a bond market event), reflecting the different patterns of trading in these markets.

On the 15 January, the ability of banks’ e-trading systems to hedge positions consistently through automatic risk management broke down as the necessary reference prices became discontinuous and unreliable. The algorithms of automatic trading have rules embedded in their code such that quotes are immediately pulled if there is a severe market liquidity event. Moreover, the algorithms often have automatic rules that activate circuit breakers or so-called “kill switches” should the aggregate notional risk on a firm’s book exceed programmed limits. On 15 January, the algorithms acted quickly to pull the so-called “streaming prices” when liquidity in the reference market for these prices dried up. Where this did not happen simultaneously, it resulted in large open positions being accumulated by the banks, quite literally within seconds, as an overwhelming balance of client sell orders were automatically executed. Once pre-determined risk accumulation limits had been breached the algorithms instantaneously shut down. Whilst each algorithm, operating independently, may well have been quite prudently calibrated to protect the bank from building an exposure that exceeded its risk appetite, collectively, the impact on market liquidity was akin, albeit temporarily, to a cascading failure across a power grid.

As a consequence, the foreign exchange market reverted to human voice orders as the substitute for automated trading. There were therefore outcomes that appear not to have been expected. So, at the risk of quoting Shakespeare inappropriately, all was well that ended (reasonably) well, but the risk that this would not be the outcome is too great to ignore.

In summary, there is good evidence that financial market conditions have evolved in ways that reduce the likelihood of continuous market liquidity in all states. One element of this is the response of regulators to the financial crisis (to which I will return later), while the other is a product of the rapid development of technology and trading strategies. The effects have probably been offset to some degree by beneficial influences from central bank monetary policy actions which have increased market liquidity. Measures of risk that reflect the overall demand for and supply of financial assets, including liquidity risk premia, remain low by historical standards, notwithstanding recent events. In part, this likely reflects the continued intended effects of monetary policy setting and the communication of policy looking forward. This has, as intended, provided an incentive for risk-taking by investors, and thus the market environment has been conducive to the so-called “search for yield”.

But, as described, underlying conditions in financial markets suggest that the current situation could be fragile . Shocks that might prompt large-scale asset disposals are of particular concern. The global asset management industry is both large in size in its own right and relative to the size of the commercial banking system.

A key issue is the degree to which asset managers (or shadow banks) typically offer short-term redemptions against potentially illiquid assets. This capacity to realise assets without unwanted disturbance to financial markets is therefore critical and is shaping the work of authorities. The risk is inherently global in nature, thereby suggesting that internationally–coordinated policy action is the preferred outcome where necessary. In the rest of my time, I will describe the work that is being done on policy responses.

First, I want to challenge the argument that the issue derives from the re-regulation of the capital and liquidity positions of banks that have in the past acted as market-makers, and thus marginal investors. This argument has a number of strands: capital and funding costs for dealer inventories in banks and broker-dealers have increased; the cost of hedging with single name credit default swaps has risen, causing availability to drop; proprietary trading restrictions (e.g. the Volcker Rule in the US) limit market making (it is too hard to distinguish prop trading from market making); and increased trade transparency requirements restrict market liquidity.)

If we look at the US as the prime example, the evidence indicates that the big run-up in inventories of fixed income securities held by the primary dealers occurred from around 2003-04 onwards, reached a peak in 2008, and has then settled back to around the 2002 level over the last two years, or so.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as reproduced in the Bank of England Financial Stability Report – December 2014

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York, as reproduced in the Bank of England Financial Stability Report – December 2014

Looked at in this light, the increase in inventory capacity in the dealer community was ephemeral, reflecting the underpricing of risk, a weak capital regime and the subsidy provided to the major banks by implicit government guarantees. Dealers de-risked their balance sheets rapidly as the crisis hit, and this reminds us that their capacity and willingness to stand in the way of major market moves (akin to catching a falling knife) was always constrained . And all of this happened before any new regulations were put in place.

Last on this point, it is worth recalling the background to the large increase in inventories from around 2002/04. Here, regulation does appear to have played a role, and not a good one. The first amendment to the Basel I capital standard came in the mid 1990s in the form of the so-called Market Risk Amendment. It enabled a substantial reduction in the capital held against trading book assets such as inventories, to a level that could be less than 1% of those assets. To illustrate this point, here is a quote from the FSA’s report into the failure of RBS.

“The capital regime was more deficient, moreover, in respect of the trading books of the banks ….. the acquisition of ABN AMRO meant that RBS’s trading book assets almost doubled between end 2006 and end 2007. The low risk weights assigned to trading assets suggested that only £2.3 billion of core tier 1 capital was held to cover potential trading losses which might result from assets carried at around £470 billion on the firm’s balance sheet.

In fact, in 2008 losses of £12.2 billion arose in the credit trading area along (a subset of total trading book assets). A regime which inadequately evaluated trading book risks was, therefore, fundamental to RBS’s failure.”).

I do not doubt that the reversal of this capital treatment of trading books has had an impact on dealer inventory levels by increasing the capital intensity. But I don’t accept that the fairly ephemeral position that emerged shortly before the crisis was fit for purpose or sustainable.

What are we therefore doing about the fragility of market liquidity and the risks to both financial stability and the state of the real economy that arise from it? First, we are working hard to understand better these risks and how they could manifest themselves. As the Bank of England’s Financial Policy Committee stated at the end of March, our concern is that investment allocations and the pricing of some securities “may presume that asset sales can be performed in an environment of continuous market liquidity.” (FPC (2015))

We are: gathering better data and thus building a greater understanding of the channels through which market liquidity can affect financial stability and economic activity; establishing a better understanding of how asset managers form their strategies for managing liquidity in their funds in normal and stressed conditions (taking into account any increase that might have occurred in the correlations between various market participants’ trading activities, such as the use of passive investment strategies); and deepening our knowledge of the contributors to greater fragility of market liquidity. The FPC has asked for a full report on these issues when it meets in September and an interim report in June.

Globally, the Financial Stability Board also has set priorities for its work, with which we are fully engaged. The intention is to understand and address vulnerabilities in capital market and asset management activities, focussing on both near-term risk channels and the options that currently exist to address them, the longer-term development of these markets and whether additional policy tools should be applied to asset managers according to the activities they undertake, with the aim of mitigating systemic risks.

The PRA, as the UK’s prudential supervisor of major trading firms, will continue to develop its capacity to assess algorithmic or automated trading, including the governance and controls around the introduction and maintenance of trading algorithms, and the potential system-wide impact of crowded positions and market liquidity. We will assess the adequacy of existing risk measurement and management practices in capturing exposures from the large volume of intraday trading instigated by these algorithms. We will continue to develop our assessment of whether trading controls deployed around algorithmic trading are fit for purpose, and in doing so we will no doubt capture insights on the role of market making on electronic platforms. This is all part of our task of supervising firms’ trading books. It should be assisted by the introduction of MIFID2 (the Markets and Financial Instruments Directive) in Europe, which will impose rules on algorithms and high frequency trading, including the introduction of circuit breakers, minimum tick sizes and maximum order-to-trade ratios, thereby seeking to improve the stability of markets.

It might be possible to conclude that it is all work to understand the problem rather than fix it. Not so, and I want to end by summarising six areas where action is already under way to reduce impediments to the development of diverse and sustainable market based finance.

First, maintaining the stability of the financial system means that we have to keep a close watch on how risks that can appear in financial markets and the non-bank financial system may wash back into and affect the critical functions performed by banks; in other words destabilise the core of the system. In order to enhance our protection against this risk, in this year’s Bank of England concurrent stress test, we are taking a substantial step to enhance the coverage of market risks. Our new approach to stress testing trading activities will capture how fast banks could unwind or hedge their trading positions in the stress scenario. This means positions that are less liquid under stress conditions will receive larger shocks. And, we have developed a new approach to stressing counterparty credit risk, which focusses on capturing losses from exposures that would become large under the stress scenario and for counterparties that would be most vulnerable in the stress scenario.

Second, the Bank of England, working with the FCA and HM Treasury has set up the Fair and Effective Markets Review to restore trust and confidence in the fixed income, currency and commodity (FICC) markets in the wake of the serious wave of misconduct seen since the height of the financial crisis. The Review is taking a fundamental look at the root causes of these abuses, the steps that have already been taken by firms and regulators to put things right, and what more is needed to deliver less vulnerable market structures and raise standards of behaviour in future. The Review will publish its recommendations in June 2015. Out of this assessment, and based on consultations to date, will I believe come priorities on market structure “standards” and transparency, effective competition, professional culture within firms and effective, pre-emptive supervision which reduces the drama of ex-post enforcement.

The third area of action concerns initiatives to improve the functioning of markets to support activity in real economies. Resilient market-based financing will help to support sustainable economic growth. The aim behind the European Commission initiative on Capital Markets Union is to strengthen markets in the EU to support growth and stability, and sustainable progress on this front will be welcome . Likewise, sound securitisation is a goal of the wider financial reform programme. The Bank of England and the ECB have published a consultation paper to identify simple, transparent and comparable securitisation techniques, the use of which should be encouraged. This work is now being taken forward in international policymaking bodies.

The fourth area of activity involves so-called securities financing transactions (SFTs) including securities lending and repurchase (repo) agreements. These can have the beneficial effects of supporting price discovery in financial markets and secondary market liquidity, and are important as part of market-making activities by financial firms, as well as their investment and risk management activities. But, as we witnessed in the crisis, they can also be a source of excessive leverage and mismatches in liquidity positions. As a consequence, some of these markets shrank rapidly as the crisis took hold. The Financial Stability Board has taken steps to introduce haircuts on SFTs that are not centrally cleared, with the aim of preventing excessive leverage becoming available to shadow banks in a boom, thereby reducing the procycliality of that leverage. The haircuts set an upper limit on the amount that banks and broker-dealers can lend against securities of different credit quality.

The fifth area concerns the risk of asset managers offering short-term redemptions to investors against potentially illiquid securities. The proportion of assets held in such structures has increased over the past decade. Given more fragile underlying market liquidity, for the reasons I have described, stressed disposals of assets might be harder to accommodate in an orderly fashion. The international securities regulatory body IOSCO, issued recommendations in 2012 that provide a basis for Common Standards for Money Market Funds (MMFs) across jurisdictions, in particular seeking to ensure that MMFs are not susceptible to the risk of runs (in the way that banks can be). More broadly, work continues on putting into practice appropriate policies and standards to prevent the risk of disorderly sales of assets in the face of investor withdrawals. Potential responses (and at this stage we are looking at options in an open way) are to require funds to hold larger liquid asset buffers to facilitate orderly redemption payments to investors, to apply more stringent leverage limits where appropriate, and to require that the redemption terms offered to investors take sufficient account of the risk that secondary market liquidity in the assets they hold could become impaired. These are possibilities, but at this stage very much not policies for the reason that a lot more work is need to properly assess them.

Last, central banks can back-stop market liquidity by acting as market makers of the last resort. The Bank of England had described in its so-called Red Book how it could act in such a way in exceptional circumstances. Here too, there is a lot more to be done to consider the circumstances in which this tool could be used.

Conclusion

The rapid trend towards greater use of market-based financing is one that should be welcomed. But, it is important that accompanying risks to financial stability are well understood and managed. Credit creation since the financial crisis has been heavily reliant on market based finance in the UK and internationally. We have to be alert to, and ready to handle the risks and consequences of any reversal in market conditions. Recent incidents of market volatility act as a reminder that it can disappear very quickly in more normal as well as stressed times. Moreover the business models of the broker-dealers that act as market makers are changing in response to the financial crisis and they are becoming reluctant to absorb large positions. In my view those changes are inevitable, because the pre-crisis state of affairs was ephemeral and unsustainable. But the impact of the change is of course important for both monetary policy and financial stability, because it affects the supply of credit to the economy and the stability of the financial system. My assessment is that in terms of understanding the risks and framing possible mitigating actions, we will fare better if we start by focussing on the activities that create such market risk, and then as appropriate move on to the entities that house those activities.

The policy response from the authorities is by nature an activity that needs to be carried out through close international co-ordination. The Bank of England is committed to playing its part, consistent with the major presence of financial market activity in the UK, alongside and as a part of the work of the G20 under the auspices of the Financial Stability Board.