Dollar deposits in their birthplace (US) are well, just dollars. Dollar deposits outside of the US are like Singlish or Ingrish and the dozens of variations across the globe. It’s the same language just in a different place. Just as dollar deposits outside of the US are still dollars.

So eurodollars are essentially all those dollar deposits outside of the US banking system. They are NOT nor have ANYTHING to do with that monetary experiment called the euro.

Eurodollars got their name originally from US dollar deposits in European banks, and in fact their origins date back to the communist days when the Ruskies and Chinese kept dollar deposits abroad (non-US banks) for fear of seizure. Today, however, they are dollar deposits in any bank outside of the US. So dollar deposits in Tokyo, Moscow, and London are all part of the eurodollar system.

What’s It Got to Do With Europe and the Euro Currency?

The term “euro” in eurodollar has as much to do with the euro currency, or the European Union, as peanut butter has to do with the solar system – nothing. You can, for example, have euroeuros or euroyen and these would be euro deposits outside of the EU and euroyen would similarly be yen deposits outside of Japan. Got it?

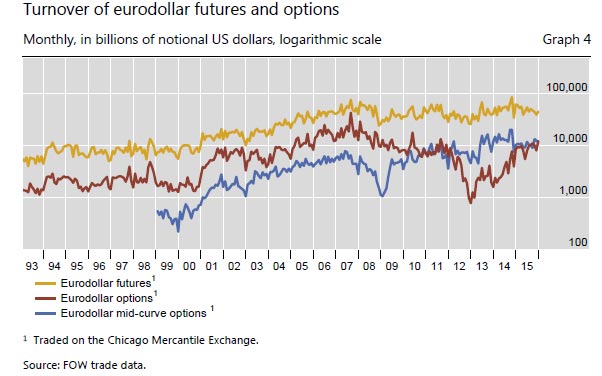

What’s important to understand is that the eurodollar system is THE biggest source of global funding, bar none. Nobody knows for sure how large it is as it’s basically a large unregulated financing system with thousands of participants globally. But we do know that the eurodollar futures market on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) is larger than S&P futures, larger than oil futures, larger, in fact, than the 10-year bond futures. It’s estimated over 90% of international trade is financed through the eurodollar market.

In fact, when cash settled eurodollar futures contracts were introduced to the CME in 1981 it was immediately the largest trading pit ever.

That so few investors know about this enormous market, its importance, and relevance is frankly pretty shocking.

Understanding the eurodollar market goes a long way to understanding why, despite the greatest monetary intervention we’ve ever seen by central banks, we’ve remained in a contractionary environment.

Our Global Financing System: Hidden in Plain Sight

The eurodollar system is a global financing system regulated by no one, influenced by many, and directly or indirectly affecting every asset price globally. Think of it as a deposit and loan market for offshore dollars. It affects asset prices because it is the wholesale financing system most used in the world. To be clear: there exist wholesale financing in other currencies (the eurocurrency market) but the dollar accounts for an estimated 75% of the eurocurrency market.

It is a critical component to how banks fund and manage their liability structures. It’s also worth pointing out that the eurodollar market is almost entirely a cashless market. It is for simplicity sake, banks’ balance sheets.

The advent of technology in finance has allowed for real time matching of assets and liabilities across financial institutions and the balancing of what are essentially banks’ balance sheets enacted with eurodollars. It is to a certain extent as close to a virtual currency as a real virtual currency like Bitcoin. Very efficient, close to instantaneous, and, in the case of eurodollars, allows for the tapping of huge pools of capital, which can be freed up for financing.

Why Should I Care?

Eurodollars provide us with what is THE best insight into global capital flows and credit demand. Problems in the eurodollar market are problems in the market. Heck, this IS the market.

The eurodollar financing market took a massive blow to the skull back in 2007, which makes sense given that so much collateral was wiped from the system.

What is both fascinating and scary at the same time is that despite all of the central bank QE programs collateral has failed to come back into the system. It’s as if the eurodollar market is suffering from concussion. We know this by looking at the eurodollar market which has never regained levels seen back in 2007.

What this tells us is that the offshore money market world is failing to produce collateral and this failure to produce collateral is reflected in the eurodollar funding markets. QE doesn’t address this problem as it is interest rate driven stimulus and this isn’t a cost of capital problem but a collateral problem.

This is deeply disturbing, and the actions taken by central banks have actually sucked high quality collateral from the system. And it is this collateral which has traditionally underpinned the wholesale funding markets, the largest of which is the eurodollar market.

Remember in 2008 when the Fed, in a blind panic, opened dollar swap lines, which they deployed in an unlimited fashion and which actually got to about $600 billion that year?

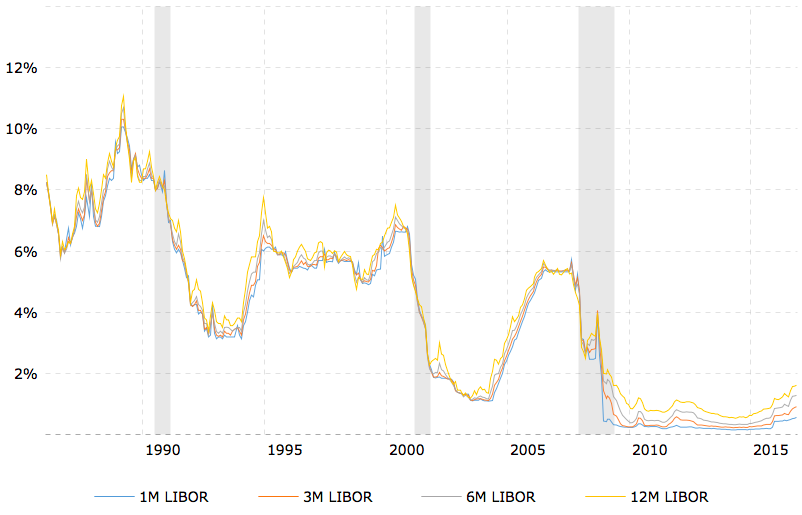

Well, what was happening was that even though the Fed had taken a chainsaw to the Fed funds rate and opened the credit spigot to full throttle, the international money markets never responded. LIBOR, which, remained elevated, which means the offshore dollar financing market was still bricking itself. Despite unlimited swap lines between the Fed and global central banks, the dollar shortage wasn’t ever resolved.

Dollar Shortage

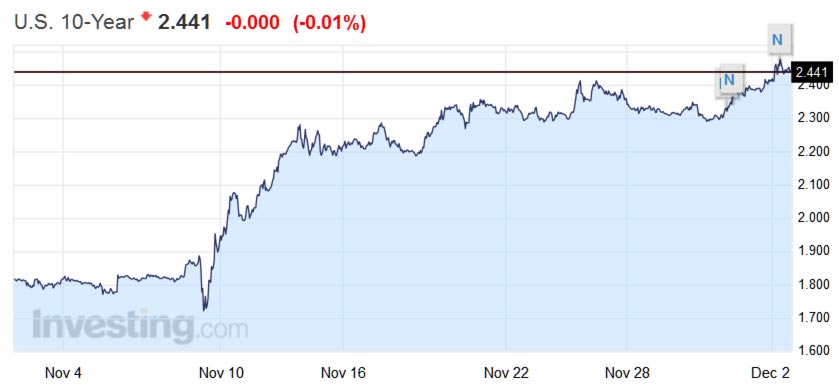

The other thing this tells us is that there is a chronic dollar shortage in financial markets, and existing dollar financing is only going to continue to be constrained as the dollar moves higher.

Remember, dollar denominated debts become increasingly unmanageable as hedging costs rise.

This creates a feedback loop whereby, in order to decrease risk, market participants either hedge dollar risk (where their collateral is in other currencies but they have USD costs somewhere in their cost structure – think European manufacturers using US technology for example). These guys hedge this exposure by buying dollars and this pushes the dollar higher.

Or market participants reduce leverage by unwinding debt positions, and, in order to do so, they have to buy back dollars as they unwind what are short dollar positions. Once again, this pushes the dollar higher.

Protectionism: Gasoline to the Fire Dollar Shortage Fire

Ok, so Trump’s promised to bring jobs back to America. It’s protectionism writ large. He’s promised to lower tax rates to incentivise those jobs to return to the US.

Whether he manages to do this or not we’ll have to wait and see. To be clear I’m unconcerned with whether this is a good or bad thing or whether Trump is an angel or a demon.

That said, understand that there’s an estimated $3 trillion in corporate US profits sitting offshore. What happens if Trump manages to pull this off?

I’ll tell you what happens. Those dollars move OUT of the eurodollar market, a market already starved of dollars, back into US banks. Uh oh! And this brings me to eurodollar futures.

Bonds, Not Currency

Ok, so we’ve just run through an admittedly extremely abbreviated discussion of the eurodollar financing market but one which hopefully provides you with some grasp of how it functions and it’s importance. As complex as the eurodollar financing market is, understand that the eurodollar futures market is a market which ultimately prices risk, and it is, I believe, the best pricing of risk we can look at in the global market.

Eurodollar futures are NOT currency futures.

Let me explain. Take Aussie dollar currency futures. These are plain vanilla currency futures. Ditto any other currency.

Eurodollar futures, on the other hand, are nothing like this as they are in fact cash settled futures contracts whose price moves in response to the interest rate offered on those dollar time deposits held in offshore (non-US) banks.

They are therefore interest rate products not currency futures and this is why I just said that this market is the best market in the world to understand global risk.

These loans or time deposits between banks are reflected in an average rate of interest charged. This is the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR).

LIBOR

The rate at which banks are borrowing from and lending to each other is therefore a derivative of the eurodollar market.

The essence of the eurodollar market is that it provides us a window into where the crowd thinks LIBOR will be at a point in the future. So eurodollars are all about expectations of the future.

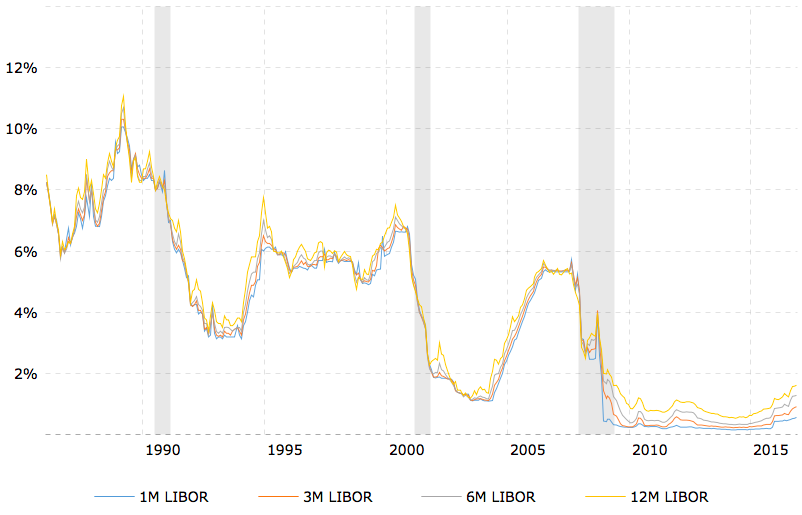

LIBOR Rates – 30 Year Historical Chart

Will the Fed Hike in December?

LIBOR, which indicates the pricing of risk in the eurodollar market, IS the market. Take a look at the chart above. Right now it’s telling us we’ll get a rate hike in December

Jonathan Moylan (pictured) was behind a hoax spread via social media that wiped millions off Whitehaven Coal’s stock price in 2013. Dean Lewins/AAP