In Glenn Stevens Opening Statement to House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics today, we get a glimpse of the drivers to lower interest rates. In addition, they are prepared to cut rates even if it leads to more growth in the Sydney property market to drive growth, even if that lever is now less powerful than previously.

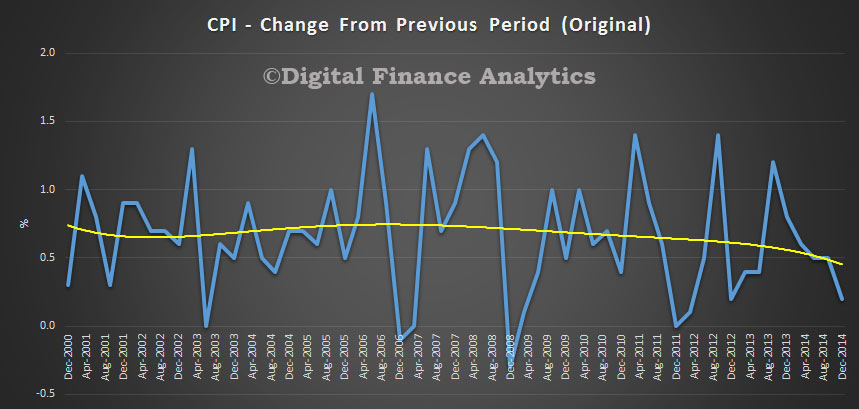

Since the hearing in August last year, the economy has continued to grow at a moderate, but below-trend pace. Inflation as measured by the CPI has been affected by movements in energy prices and government policy changes, but even aside from these effects, inflation is low and appears likely to remain so.

The international context is one in which the global economy likewise is growing, but according to most observers at a pace a little below its longer-run average. There are some notable differences in performance by region. The US economy has picked up momentum, growing above trend with a falling unemployment rate. China’s economy met its growth target in 2014. A slightly lower target seems likely to be set for 2015, perhaps something like 7 per cent. But that would still be robust growth for an economy of China’s size. On the other hand, the euro area and Japan have recorded lower growth rates than expected a year ago.

Commodity prices have fallen, in some cases quite sharply. These trends appear to reflect primarily major increases in supply, with some moderation in demand playing a role. That would appear to be the case for iron ore and oil prices (and, prospectively, liquefied natural gas prices, which are typically tied to oil prices). Base metals prices, where few significant supply changes have occurred, have fallen by much less.

So there has been what economists refer to as a ‘positive supply shock’: more of the product is available with lower prices. The effect of this on individual countries will vary, depending on whether they are a producer or a consumer of such raw materials. On the whole for the global economy, however, this is a positive development.

Inflation is quite low in a range of countries, and very low in some. The decline in energy prices is temporarily pushing headline CPI inflation rates even lower.

The very low interest rates in evidence around the world when we last met have fallen further. This has been most pronounced in Europe, where yields on long-term German sovereign debt have fallen to be about the same as those in Japan. German sovereign debt has recently traded at negative yields for terms as long as 5 years. Official deposit rates are negative in the euro area, and the European Central Bank has announced a large-scale asset purchase program – colloquially referred to as ‘quantitative easing’. The euro has depreciated. Some surrounding countries to which funds tend to flow in anticipation of further depreciation – such as Switzerland – have reduced interest rates to significantly below zero and indeed 10-year Swiss government debt has traded at a negative yield. The Swiss National Bank took the decision to remove the cap on the Swiss franc, as it assessed that the size of the intervention likely to be required to hold it was becoming just too large. This move occasioned considerable turbulence in foreign exchange markets.

Meanwhile, the US Federal Reserve, faced with a strengthening US economy and having ended its asset purchase program last year, is expected to begin a gradual process of lifting its policy rate in a few months from now. So the monetary policies of the major jurisdictions look like they will be heading in differing directions. This means there is ample potential for further turbulence in financial markets this year.

The falls in prices for key export commodities are lowering Australia’s terms of trade and hence the purchasing power of our national income. This is a well-understood mechanism and has been the subject of much discussion. It will continue to constrain income growth for households and mining companies, and revenues for both state and federal governments, over the period ahead.

Resource export shipments are increasing strongly, as the capacity put in place by the period of high investment is put to use. At the same time, the high levels of capital spending by the resources sector, which had been a strong driver of domestic demand for several years, peaked during mid 2012 and turned down. All indications are that this downswing will accelerate this year. That has always been our forecast. The recent declines in commodity prices don’t change it, though they do reinforce that this trend is well and truly under way.

The various areas of domestic demand outside mining investment are mixed. Dwelling construction is rising strongly and commencements of new dwellings will reach a new high over the coming 12 months. Consumer spending is responding both to income trends and financial incentives, which are pulling in different directions. Growth in wages, by historical standards, is quite subdued. This and the fall in the terms of trade is working to restrain growth in disposable incomes. Working the other way, the fall in petrol prices, assuming it persists, is adding noticeably to the real incomes of consumers. Increased asset values, which push up gross measures of wealth, and low interest rates are also working to push consumption up relative to income. The net effect of these opposing forces is producing moderate, though not strong, consumption growth.

Meanwhile, at this point non-mining business investment spending is still very subdued. While several key fundamentals are in place for stronger performance, clear signs of a near-term strengthening remain unconvincing at this stage. This is a weaker outcome than we had expected six months ago. Public sector final spending – about one-fifth of aggregate demand – is fairly subdued, and the intent of governments, as you know, is to restrain their own spending over the period ahead. The lower exchange rate is likely to help export volumes outside the resources sector, and of late better trends have been observed in some services export categories including tourism and education.

Overall, growth in non-mining economic activity has picked up, but is still a little below average. Our expectation had been that a further pick-up would occur in 2015. When we reviewed our forecasts in late January, we didn’t feel that growth in the recent past had been materially different from what we had estimated a few months ago. But when we tried to look ahead, we concluded that there were fewer signs of a further pick-up in non-mining activity than we had hoped to see by now. As a result, the revised forecasts we took to the February Board meeting embodied a longer period of below-trend growth, and a higher peak in the rate of unemployment, than earlier forecasts. They also suggested that inflation was likely to remain pretty low over the forecast horizon. The inflation outlook was revised slightly lower, in part reflecting the effect of declining oil prices as well as the weaker outlook for economic activity.

At its meeting in February the Board considered that this revised assessment – that is, sub-trend growth for longer, a higher peak in the unemployment rate, slightly lower inflation – warranted consideration of some further adjustment to monetary policy, after a fairly long period during which the cash rate had remained steady. These were incremental changes to the outlook but all in a consistent direction.

Another factor in our consideration was dwelling prices, which have continued to increase. Price rises in Sydney are very strong, and they are pretty solid in Melbourne. On the other hand they are much more mixed elsewhere. Excluding Sydney, the rise for Australia as a whole over the past year was about 5 per cent. That is a healthy pace but not alarming, and some cities have seen price falls. Developments in the Sydney market remain concerning, but in the end we did not see these trends as overwhelming a case for a further easing in monetary policy that was made on more general grounds.

I note that, on the regulatory front, APRA has announced its supervisory approach to managing the potential risks posed by the rise in lending to investors in housing. This involves more intense scrutiny of investor loan portfolios growing at over 10 per cent per year, with the possibility, ultimately, of additional capital being required if APRA deems it necessary. APRA has also reiterated its expectations for other elements of lending standards such as interest rate buffers and floors. And ASIC has begun a review of interest-only lending in the context of consumer protection legislation. The Bank welcomes these steps and will keep working with other regulators in these areas.

The Board is also very conscious of the possibility that monetary policy’s power to summon up additional growth in demand could, at these levels of interest rates, be less than it was in the past. A decade ago, when there was, it seems, an underlying latent desire among households to borrow and spend, it was perhaps easier for a reduction in interest rates to spark additional demand in the economy. Today, such a channel may be less effective. Nonetheless we do not think that monetary policy has reached the point where it has no ability at all to give additional support to demand. Our judgement is that it still has some ability to assist the transition the economy is making, and we regarded it as appropriate to provide that support.

The forecasts published last week in the Statement on Monetary Policy assume a lower path for interest rates and a lower exchange rate than both earlier forecasts and the ones the Board responded to at the February meeting. These are assumptions rather than forecasts or commitments to a course of action.

It is worth noting that, despite concerns at various times about whether the exchange rate would adjust appropriately to our changing circumstances, it has been doing so over the period since we last met with the Committee. Against the US dollar it has fallen by around 17 per cent since our last hearing. The US dollar itself has been rising against all currencies, of course, so much of this movement is an American story rather than an Australian one. Against a basket of relevant currencies the Australian dollar has fallen by less, but the decline is still about 11 per cent since August. Further adjustment is probably going to occur.

One other development since our last meeting with the Committee was the final report of the Financial System Inquiry. This was quite a wide-ranging report and there is now a further period of consultation. I simply note that the Inquiry did not find major problems in the financial system, but did make recommendations about capital, to enhance the resilience of the banking system, and about loss-absorbency more broadly in the context of resolution. These will be mostly in the province of APRA to consider. The Inquiry also made some observations about payments matters, generally supporting the steps the Payments System Board has taken since its inception in 1998, and pointing to some areas where further steps may be appropriate. The Payments System Board will be considering these matters at its meeting next week.