Economist John Adams visited the Melbourne suburb of DonnyBrook (3064), and sees parallels to Ireland before the great crash.

We discuss the implications.

Digital Finance Analytics (DFA) Blog

"Intelligent Insight"

Economist John Adams visited the Melbourne suburb of DonnyBrook (3064), and sees parallels to Ireland before the great crash.

We discuss the implications.

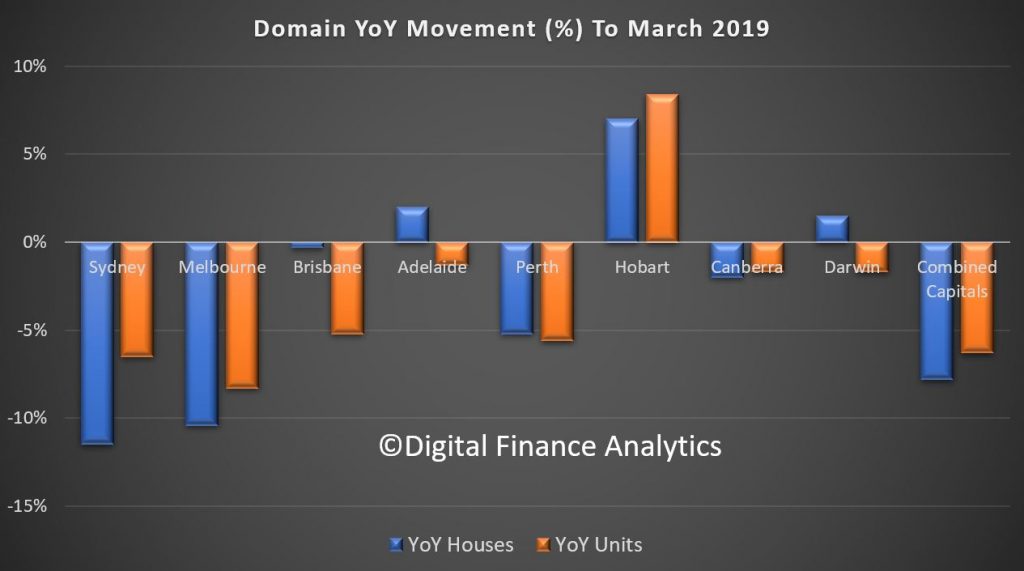

Domain has released their March quarter 2019 house price data. Sydney, Melbourne and Perth are bearing the brunt of the falls, alongside units in Brisbane, according to their statistics. Hobart remains the most buoyant but buyer interest appears to have passed its peak . And of course remember these are average figures which mask local changes.

They says that Sydney’s current property downturn is the sharpest in more than two decades. It is yet to surpass the duration of the 2004-06 slump but it is coming close to being the longest. Sydney house prices have fallen 14.3 per cent from the mid-2017 peak. If the pace of quarterly decline remains, prices are likely to dip below $1 million in the coming quarter. A six-figure median house price has not been recorded in four years. Sydney unit prices have fallen 9.9 per cent from the mid-2017 peak. For the first time in three years unit prices are below $700,000.

Despite further price deterioration to house and unit prices over the quarter, the rate of decline has eased from the quarterly falls recorded last year. House prices are now back to early 2016 and units back to mid-2015. However, house prices are 30.2 per cent higher and unit prices 20.7 per cent higher than five years ago, providing many homeowners with substantial equity gain.

Melbourne is currently facing its steepest downturn in more than two decades. House prices have fallen for five consecutive quarters, down 11 per cent from the peak reached at the end of 2017. Unit prices have held firmer, with price falls shorter and less severe relative to houses. Unit prices have deteriorated for four consecutive quarters, pulling prices back 8.3 per cent from the peak notched a year ago.

The Melbourne property market started 2019 better than 2018 ended, with auction clearance rates nudging higher (admittedly from lower volumes), views per listing rising marginally, and banks now actively seeking new business. The rate of house price declines have eased over the latest quarter.

Greater Brisbane house prices have stalled following six years of continuous annual growth, with prices flatlining over the year. Homeowners may not be reaping equity gain but flat house prices is a better outcome than a fall, which is what’s playing out across most capital cities.

The housing market remains fragmented with houses outperforming units. This has been a trend since mid-2012. Unit prices are 9.6 per cent below the mid-2016 peak, with buyers now able to reap the benefits of purchasing at 2013 prices. Significant supply numbers have weighed heavily on unit prices. Although listing volumes are shrinking, it has not been enough to translate into price growth yet.

House prices in Adelaide have bucked the national downward trend and became one of only three capital cities to rise over the year. Homeowners have reaped the benefit of almost six years of steady annual house price growth. House prices may have flatlined over the quarter, but it is the second best outcome of all the capital cities, behind Hobart. The sustainable pace of annual growth has slowed to a five-and-a-half year low. This weakness provides further evidence that credit access is having an impact on markets that would otherwise have steady growth.

Adelaide is now the third most affordable city to purchase a house, surpassing Perth’s median house price for the first time since 1993. House prices currently remain higher than Hobart, but galloping Hobart prices mean the price gap is at a 12-year low. Adelaide’s unit prices have marginally fallen from the record high achieved last quarter, but remain the most affordable of all the capital cities.

Early indicators previously displayed some encouraging signs of a recovery in Perth’s housing market. However, over the first quarter of this year, house and unit price falls have gathered pace. House prices are now 14 per cent and unit prices 16.6 per cent below the 2014 peak.

Buyers continue to have the upper hand. Improved affordability is providing the ultimate silver lining for prospective homeowners, allowing a purchase to be made at 2011 prices. Perth’s recovery is being hindered by a more restrictive lending environment at a time when local confidence is subdued under weak economic conditions. A sluggish economy is being dragged down by high unemployment, a tight consumer purse, and weak population growth.

Hobart bucked the national downward trend, and remains the best performing city for capital growth. It became the only city to record growth over the quarter and year for both houses and units. Despite this, the pace of house price growth has slowed to half of that recorded over the same period in 2018, providing homeowners the lowest annual growth since mid-2016. In the space of a year-and-a-half, Hobart has gone from the most affordable city to purchase a unit, to more expensive than Adelaide, Darwin and Perth. If the pace of growth continues, Hobart unit prices are likely to overtake Brisbane’s in the coming months.

Hobart became a hotspot for investors, a destination for interstate buyers seeking the ultimate lifestyle location, and tourism flourished helping to drive economic growth and place pressure on housing demand. Buyer interest appears to have passed its peak, with Domain recording a slip in the number of views per listing over the past two months. It is likely that capital gains will be more subdued than the double-digit growth recorded last year.

Canberra’s housing market has shown the first signs of price weakness since 2012. House prices had their steepest annual fall in a decade, following a stint of continuous growth that spanned roughly six years. Despite this, the nation’s capital has a tendency to be the quiet achiever, providing homeowners with steady equity growth. Historically, any pullback in house prices tend to be short and relatively minor, apart from the 1995-97 downturn. Current market conditions are likely to be the same, a short period of softening rather than the correction currently unravelling in Sydney and Melbourne.

Unit prices continue to slide over the quarter and year, with the market failing to produce a steady period of price growth since 2009-10. The outlook for apartment prices has been mixed, providing only subdued capital growth over the past five years, up by 4.5 per cent. Equity growth in houses has been superior at 25.8 per cent.

The peak of Darwin’s housing market is in the rear-view mirror – with prices hitting a high during 2013-14. House and unit prices continue to be impacted from the weak economic conditions that have ensued post the mining boom, with a soft employment sector and lack of migration weighing on the demand for housing. A recovery in Darwin’s housing market largely hinges on the government’s attempts at boosting the population, jobs growth and an improvement in the availability of housing credit.

The latest edition of our weekly finance and property news digest with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Drawing from his direct experience in the market, mortgage broker and financial adviser Chris Bates and I discuss the latest issues and consider the impact of negative gearing reform.

Chris can be found at www.wealthful.com.au & www.theelephantintheroom.com.au plus via LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/christopherbates

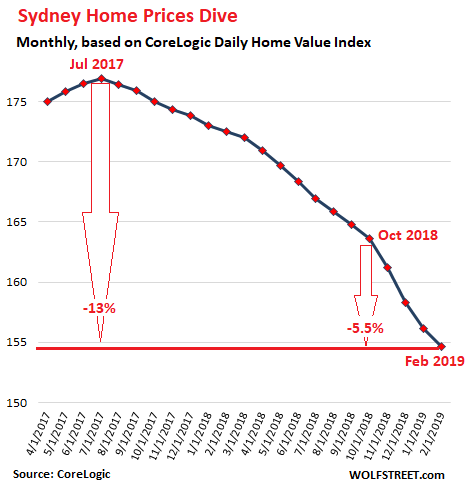

Across the metro area of Sydney, prices of all types of homes combined, according to CoreLogic’s Home Value Index, fell 1.0% in February from January, 10.4% from a year ago, and nearly 13% from its peak in July 2017. Just over the past four months, the index has dropped 5.5%:

The volume of closed sales recorded in Sydney in February plunged 20.6% from the already weak sales in February last year, according to CoreLogic’s report.

Units, generally the lower end of the market, is where first-time buyers are thought to have a chance, and they were considered the saving grace in this market. But prices continue to drop, and the industry’s hope that first time buyers would bail out this market is now fading.

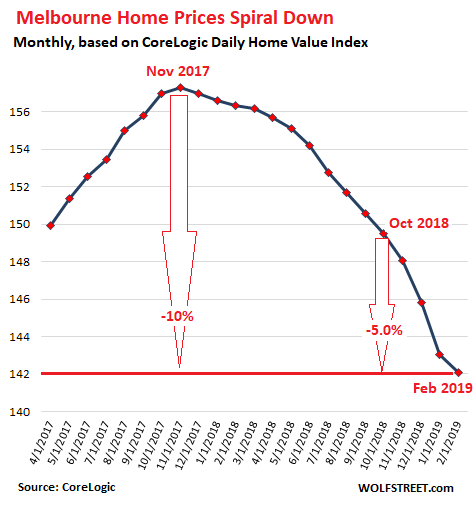

In the Melbourne metro, the second largest market in Australia, prices of all types of homes fell 1% for the month and 9.1% year-over-year, according to the CoreLogic Home Value Index. The index is now down nearly 10% from the peak in November 2017. Over just the past four months, the index for Melbourne dropped 5.0%:

House prices in Melbourne dropped 1.2% for the month and 11.5% year-over-year. Condo prices dropped 0.6% for the months and 3.7% year-over year. CoreLogic estimates that closed sales in Melbourne plunged 22.1% in February from the already weak sales a year ago.

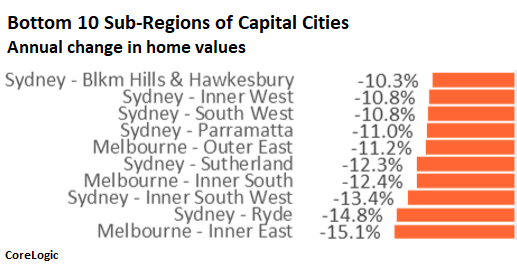

Of the bottom 10 sub-regions of Australia’s capital cities seven were in the Sydney metro and three were in Melbourne (chart via CoreLogic):

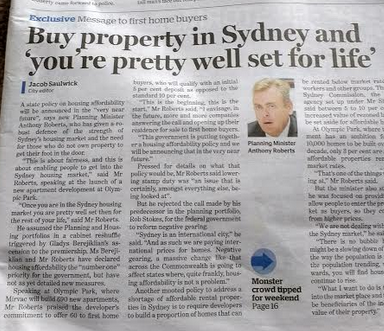

As Wolf Street highlights, there is a bitter irony to all this. In February 2017, just months before the market in Sydney peaked, Anthony Roberts, New South Wales Minister for Planning and Housing, was promoting the launch of a 690-unit apartment development at Olympic Park, a suburb of Sydney, heaping praise on the developer for having reserved 60 units for first-time buyers.

Roberts was hyping new incentives for first-time buyers, including a reduction of the down-payment to 5%, to lure them into the Sydney housing market:

“This is about fairness, and this is about enabling people to get into the Sydney housing market. Once you are in the Sydney housing market, you’re pretty well set then for the rest of your life.”

The metros of Sydney and Melbourne, due to their enormous size and high prices, dominate the national home values, but weakness is now spreading to other capital cities, with only Hobart and Canberra still showing year-over-year gains (in parenthesis, CoreLogic’s measure of “median value”):

On a national basis, the CoreLogic Home Value Index dropped 6.3% year-over-year and 6.8% from its peak in October 2017. It’s now back where it had been in September 2016. CoreLogic’s report points out that, despite the decline, the index remains 18% higher than it had been five years ago, “highlighting that most home owners remain in a strong equity position.” Only recent buyers are underwater.

That’s a calming thought, even for the Reserve Bank of Australia, according to the minutes for its Monetary Policy Meeting on February 5, 2019, when it decided to maintain its policy rate at the record low level of 1.5%:

From a longer-run perspective, members assessed that, following such large increases in housing prices, the effect of the recent price falls on overall economic activity was expected to be relatively small.

From a financial stability perspective, tighter lending standards, an improving labor market and low interest rates were all likely to support households’ capacity to service their debt.

Few households were in negative equity positions despite the falls in housing prices, implying that banks’ losses would be limited even if household financial stress were to become more widespread.

The IMF was less sanguine in its assessment of Australia. It found that “the financial sector faces continued vulnerabilities from high household debt, still-stretched real estate valuations, and banks’ ongoing dependence on funding from global markets.”

The assessment “recommended further steps to bolster financial supervision as well as to reinforce financial crisis management,” which might be a good idea.

We look at the latest real estate data from the US, where sales volumes are falling and home price growth is stalling.

And we read across to the local scene, where despite the hype about auction clearance rates, home price falls are accelerating. Indeed, we expect more ahead.

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to the 23rd of February 2019 – our digest of the latest finance and property news with a distinctively Australian flavour.

Watch the video, listen to the podcast or read the transcript.

The gap between the real data on housing and finance and the narrative offered by the RBA continues to wide, plus more on banking separation, which is now running on a new set of legs, and the markets are backing the end of the Trade Wars just as China turns off the tap to some Australia coal exports. But people are claiming its just a little local difficulty.

And by the way, if you value the content we produce, please do consider supporting our efforts. You can make a one off donation via PayPal here is the link, or consider joining our Patreon programme. We really appreciate your support to help us continue to make great content.

Governor Lowe appeared before the House Standing Committee On Economics which took place on Friday. The session was streamed in audio only (a poor show that they were unable to arrange a web show, as its was hard to follow who was talking) and a transcript has been released. He said that the RBA’s central scenario for this year is for growth of around three per cent, inflation of around two per cent and unemployment of around five per cent. The economy is benefiting from increased spending on infrastructure and a pick-up in private investment as capacity utilisation has tightened. The strong growth in jobs is also supporting spending, as is the sustained low level of interest rates. Looking beyond income growth, developments in the housing market can also affect overall spending in the economy. Lower turnover means less of the spending that occurs when people move homes. Declining housing prices also make some people feel less wealthy, so they spend less, although this effect doesn’t look to be particularly large. Lower housing prices are also associated with less construction activity in the economy, so these are the areas that we’re keeping a close watch on. This adjustment in the housing market is not expected to derail our economy. It will put our housing markets on more sustainable footings, and it will allow more people to purchase their own home.

There are some wealth effects from declining housing prices, but they’re relatively small. We’ve got to remember that in Sydney and Melbourne prices are still up 70 or 80 per cent over a decade, so most people are sitting on very substantial capital gains. People who purchased in the last year or 18 months are not, but most people are sitting on substantial capital gains, so there are still positive wealth effects coming from that. It’s largely the income story which doesn’t get talked about enough, because the media love talking about property prices, but year after year of weak income growth finally weighs on our spending plans, so both the pick-up in wage growth and the tax cuts will boost disposable-income growth.

There were three points to take away. First the RBA is holding to its view that eventually wages will start to rise, despite the results reported by the ABS this week. The trend Wage Price Index (WPI) rose 0.5 per cent in December quarter 2018 and 2.3 per cent through the year, according to figures from the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Growth remains anaemic. The trend quarterly rise of 0.5 per cent continues an extended period of moderate hourly wage growth. Annually, private sector wages rose 2.3 per cent and public sector wages grew 2.5 per cent.

Second, Lowe played down the home price falls, and argued this had little to do with APRA tightening lending standards as banks are still lending, and offering discounted rates for new loans.

Third, the RBA will use monetary policy to trim the economic sails, including expected tax cuts and even a lower US dollar, but accepted that QE could be used in certain scenarios, if required. Dr Lowe said “I would very much hope that we don’t have to go down that route. If the economy were to slow significantly, there are multiple margins of adjustment—things that could be done. We could lower interest rates further; of course, there could be a fiscal stimulus; and the exchange rate would adjust. So all those margins of adjustment could take place before we would need to consider this, but in extremis there are scenarios where that would have to be seriously considered.

And by the way, they played down the potential impact on asset prices if QE were to be activated.

So I came away with a view that the RBA’s perspective continues to be rosy, perhaps too rosy and the impact of tighter credit, the easing credit impulse and lower loan to income multiples seem unimportant. I found this predictable. But remember they have said recently they are not sure what level of debt would be too much, implying we are not there yet. Given the high household debt ratios in Australia, this is lack of focus on debt is disgraceful.

The Bank of England this week in a blog on Bank Underground “What goes up must come down: modelling the mortgage cycle” – said “it is critical for economists and policymakers to understand the drivers of the mortgage credit cycle. On the one hand, it is important for policymakers to know how the housing cycle and mortgage structure affect the transmission of monetary policy. On the other hand, spotting the signs of a potential mortgage market slowdown early on might help to avoid some of the detrimental impacts from future events similar to those that took place a decade ago”.

We agree, and I must question whether the RBA does. And I have to say, I felt the Governor had a very easy time in the committee, other than the QE discussion. The rest was all puff.

In contrast we ran our live show this week, taking questions from our audience of more that 600 real-time viewers. We updated our property scenarios to take account of a range of new data, and the latest input from our household surveys. A peak to trough home price fall of 20-30% over 2-3 years remains our base case, but with risks to the downside. On the other hand, the RBA’s base case gets only a 1% probability now.

The factors we have considered include: Lower inflation and growth rates ahead according to the RBA, Fed future rate hikes on hold, Potential for more QE (Euro Zone, Japan, others), Recent home price falls in Australia driven by weaker credit impulse, Underemployment still a significant issue and wages flat. We also have used updated households’ intention to transaction data, mortgage stress and affordability metrics. In passing it’s worth noting that ANZ revealed their mortgage underwriting standards are now ~20% tighter, though they are focussing more on investor lending ahead. Other Banks are even tighter. “Mortgage Power” has been significantly curtailed. Here are the results from our Core Market Model, with a probability rating and here is a summary of the scenarios.

You can watch a recording of our live event.

The AFR this week carried a story suggesting that over-valuation of properties was widespread and were partly driven by real estate agents trying to generate more revenue through advertising campaigns paid for by the vendor, which then generate commissions and other incentives from advertising companies. The higher the forecast price of a property the more is likely to be spent on advertising. A lot of agents are losing money. The kickbacks help keep their businesses running. This is something which our Property Insider Edwin Almedia highlighted recently in our post “Breaking With Tradition”.

I was quoted in the article – “Martin North, principal of Digital Finance Analytics, an independent consultancy, said discounts of more than 40 per cent were also being made in Victoria’s Red Hill, a leafy weekend retreat about 82 kilometres south-east of Melbourne, and Sydney suburbs including Box Hill and Agnes Banks. “Typically, in a downturn it’s the top end of the market which dies first, and the decay in price spreads down the market like a canker,” said Mr North. He estimated one-in-ten households were in negative equity, where the value of the mortgage is bigger than the expected realisable value of the property.

The AFR went on to say the falls are out-pacing predictions by major lenders, such as Gareth Aird, senior economist for Commonwealth Bank of Australia, the nation’s largest lender. Mr Aird said property prices will this year fall by about 5 per cent in Sydney and 6 per cent in Melbourne. That would take the fall in Sydney prices from their July 2017 peak to around 15 per cent and 13 per cent in Melbourne. Mr Aird expects the national peak to trough falls to be about 12 per cent. Good luck with that!

LF Economics report which we discussed in our post “Crisis – What Crisis? The Latest On Home Prices” is more realistic, saying a “bloodbath” is possible with falls this year in Melbourne and Sydney – before allowing for inflation – of between 15 per cent and 20 per cent. This could rise to 25 per cent if the finance and housing markets continue to deteriorate. I discussed this on Seven Sunrise and left Kochie all but speechless…. Its worth watching the video just for that!

And the IMF reported on Australia this week. Directors noted that although growth is expected to remain above trend in the near term, a weaker global economic environment, high household debt, and vulnerabilities in the housing sector could weigh on medium‑term growth. Against this background, they highlighted the importance of maintaining supportive macroeconomic policies to secure stronger demand momentum, address macrofinancial risks, and boost long‑term productivity and potential growth.

Directors welcomed the authorities’ macroprudential interventions to reduce credit risk and reinforce sound lending standards. They concurred that, with high prices for residential real estate along with elevated household debt, macroprudential policies should hold the course on the improved lending standards and further strengthen bank resilience by refining the capital adequacy framework. Directors also saw merit in expanding and strengthening the macroprudential toolkit to allow for more flexible responses to financial stability risks.

Directors underscored the need to remain vigilant about housing market developments. They noted that while the housing market correction is helping housing affordability, continued housing supply reforms remain critical for broad affordability and to reduce macrofinancial vulnerabilities. Directors generally encouraged the authorities to explore, where possible, alternative and effective non‑discriminatory measures for buyers.

Or in other words, find ways to keep the housing bubble alive, despite the risks. I see the hand of Treasury here! Also, it’s worth noting that the Output Gap and Fiscal Balance for Australia is considerably worse that New Zealand, with Australian net debt at 15%, worse than New Zealand, though better than Canada or the UK. New Zealand has generally had countercyclical fiscal policy, and this is reflected in the evolution of its net debt to GDP ratio. Australia is not dealing with either private debt or international debt, though there is a little more attention on public debt. But this does not bode well. All this in the context of rising global debt, which has reached another new record.

And here is the killer slide. The question to ask is why did prices take off around the year 2000. The answer is stupid tax policy as Peter Costello halved the capital gains tax on property, and with negative gearing led to a plain stupid rise as investors crowded into the market. Of course the reverse will also be true, as investors are already deserting the field, and Labor, if the win, trims the tax breaks, to get back to a more normal housing market. Despite the pain, that would be a good thing, but we still must deal with the legacy of debt. The words I quote before from the Bank of England ring in my ears!

We have argued that the Royal Commission into Financial Services Misconduct passed on the main reform area – structural separation. As Paul Keeting, the architect of financial deregulation in the 1980’s said in the Australian “The royal commissioner should have recommended — this conflict between product and advice — be prohibited. This he monumentally failed to do. He should have acted upon the examination and the evidence of these serious conflicts of interest.”

But the torch has been picked up in the Senate, and a 3 month inquiry is now in train. This is a golden opportunity to push hard at getting a better structure for the sector. I discussed this with CEC’s Robbie Barwick see “Another Swipe At Banking Supervision”. There is a chance now to make a submission to the Senate Inquiry, and I encourage you to do this – via the online submission process. And to assist, I will be releasing a video in a few days with some key points and a how to…. We can really make a difference.

Another issue, Broker remuneration continues to flare, as the industry attempts to push back on the idea of replacing broker commissions with a fee paid for by prospective borrowers. Now both sides of politics have gone coy on this, citing competition -related issues. And this week Labour came out with the idea of a scaled fee of 1.1% being paid for by the banks for mortgage applications. That misses the point, because it still means a bigger loan translate to a bigger payment to a broker, so conflict of interest would still exist. Perhaps the best option would be a flat fee, paid by the bank, as, after all the bank is outsourcing an element of its loan processing to the broker. Labor has lost the plot here, but at least they still support best interests and the removal of trail commissions.

Finally, home prices fell again according to Corelogic, taking the fall from peak in Sydney to 13% and in Melbourne to 9.5%, and in Perth its 17.4%. Auction clearance rates were still slightly higher than before Christmas, at 51.2% on 1,259 auctions, well down on last year. Sydney ended at 54.6% and Melbourne at 52.5%. I continue to see accelerated weakness in Melbourne. Nothing here is signal signs of a bounce, despite the spruikers. As McGrath put it in their results release”

Economic factors are contributing to a significant reduction in transaction volumes with settled sales for the reals estate sector nationally down 13.2% and across the eastern seaboard Sydney is down 20.3% and Melbourne down 22.3% and Brisbane down 11.3% on the 12 months to January 2019. This is shown in their share price which is down 36.9% over the past year.

IN the US markets, te S&P 500 posted its highest closing level since Nov. 8 on Friday as investors clung to signs of progress in the ongoing trade talks between the United States and China. Investors assessed a slew of headlines on the talks, with top trade negotiators from the two countries meeting to wrap up a week of discussions on some of the thorniest issues in their trade war. If the two sides fail to reach a deal by midnight on March 1, then their seven-month trade war could escalate.

Optimism on the trade front and dovish signals from the U.S. Federal Reserve have driven the recent gains and left indexes well above their lows of December, when the market swooned on fears of an economic slowdown.

U.S. President Donald Trump was reportedly set to meet with China’s top trade negotiator, Chinese Vice Premier Liu He, as the world’s two largest economies scramble to reach a trade deal before the U.S. increases tariffs on around $200 billion in Chinese imports on the March 1 deadline.

Markets have been closely following the standoff between China and the U.S. amid concerns of the negative impact on the global economy and the meeting between Trump and Liu is taken as a sign of progress in reaching a deal.

The S&P 500 is now up about 19 percent since its late-December low.

The S&P 500 technology index was up 1.3 percent, leading gains among the 11 major S&P sectors, while the trade-exposed industrials index climbed 0.6 percent.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 181.18 points, or 0.7 percent, to 26,031.81, the S&P 500 gained 17.79 points, or 0.64 percent, to 2,792.67 and the Nasdaq Composite added 67.84 points, or 0.91 percent, to 7,527.55.

All three indexes registered gains for the week, with both the Dow and Nasdaq posting a ninth week of increases.

Oil prices headed higher on Friday, on track for a second consecutive weekly rise, as progress in U.S.-China trade talks adjusted expectations for global demand higher in the hope of a deal. Evidence that trade tensions between the world’s two largest economies may be thawing, together with OPEC-led production cuts, have translated into a rally of more than 20% this year, though concerns remain over surging U.S. production. The Energy Information Administration reported Thursday that weekly production stateside hit a record high of 12.0 million barrels per day.

European Union Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom said Friday that a trans-Atlantic trade deal could be achieved before year-end, as the economic bloc hopes to avoid the threat of U.S. automotive tariffs. The U.S. and Europe ended a stand-off of several months last July, when Trump agreed to hold off on car tariffs while the two sides looked to improve trade ties

So, the housing sector continues to look weak, and credit remains tight. The Financial Crisis is so close now, you can almost smell it. In fact you can get a nice overview over at Nuggets News. I provided several comments to the show, alongside Roger Montgomery, entitled “Australia A Coming Financial Crisis”. I will put a link in the comments. Here is a flavour. It’s a good reflective piece, Alex did a great job putting it together.

We review the latest from LF Economics on home prices, and include a segment on Sunrise today where I discuss the trajectory of property valuations.

A quick review of the DFA contribution to 60 Minutes aired last night.

We covered the issues of home price falls, negative equity and property construction standards.

See our more detailed post on negative equity.

As featured on 60 Minutes, using data from our core market model we have mapped the hot spots across the country, as home prices fall.

Negative equity is a brake on mobility and economic growth and is the result of rabid home lending and price growth, now going into reverse.

This show discusses our approach, and highlights the most impacted post codes, with data to end January 2019.

We will run the modelling again next month, as prices continue to move.