Mortgage Lending is slowing and banks are tightening their underwriting standards still further, so what does this tell us about the trajectory of home prices, and the risks currently in the system?

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to 30th September 2017. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

Welcome to the Property Imperative weekly to 30th September 2017. Watch the video, or read the transcript.

We start our review of the week’s finance and property news with the latest lending data from the regulators.

According to the RBA, overall housing credit rose 0.5% in August, and 6.6% for the year. Personal credit fell again, down 0.2%, and 1.1% on a 12-month basis. Business credit also rose 0.5%, or 4.5% on annual basis. Owner occupied lending was up $17.5 billion (0.68%) and investment lending was up $0.8 billion (0.14%). Credit for housing (owner occupied and investor) still grew as a proportion of all lending. The RBA said the switching between owner-occupier and investment lending is now $58 billion from July 2015, of which $1.7 billion occurred last month. These changes are incorporated in their growth rates.

On the other hand, data on the banks from APRA tells a different story. Overall the value of their mortgage portfolio fell 0.11% to $1.57 trillion. Within that owner occupied lending rose 0.1% to $1.02 trillion while investment lending fell 0.54% to $550 billion. As a result, the proportion of loans for investment purposes fell to 34.9%.

This explains all the discounts and special offers we have been tracking in the past few weeks, as banks become more desperate to grow their books in a falling market. Portfolio movements across the banks were quite marked, with Westpac and NAB growing their investment lending, while CBA and ANZ cutting theirs, but this may include loans switched between category. Remember that if banks are able to switch loans to owner occupied categories, they create more capacity to lend for investment purposes. Putting the two data-sets together, we also conclude that the non-bank sector is also taking up some of the slack.

Our mortgage stress data got a good run this week, with the AFR featuring our analysis of Affluent Stress. More than 30,000 households in the nation’s wealthiest suburbs are facing financial stress, with hundreds risking default over the next 12 months because of soaring debts and static incomes. This includes blue ribbon post codes like Brighton and Glen Iris in Victoria, Mosman and Vaucluse in NSW and Nedlands and Claremont in WA.

The RBA is worrying about household debt, from a financial stability perspective, according to Assistant Governor Michele Bullock. She said households have really high debt – mainly mortgages, as a result of low interest rates and rising house prices, and especially interest only loans. “High levels of debt does leave households vulnerable to shocks.” She said. The debt to income ratio is rising (150%), but for some it is much higher. We will release our September Stress update this coming week.

Debt continues to remain an issue. For example, new data from the Australian Financial Security Authority shows that in 2016–17, the most common non-business related causes of debtors entering personal insolvencies was the excessive use of credit (8,870 debtors), followed by unemployment or loss of income (8,035 debtors) and then domestic discord or relationship breakdown (3,222 debtors). However, employment related issues figured first in WA and SA.

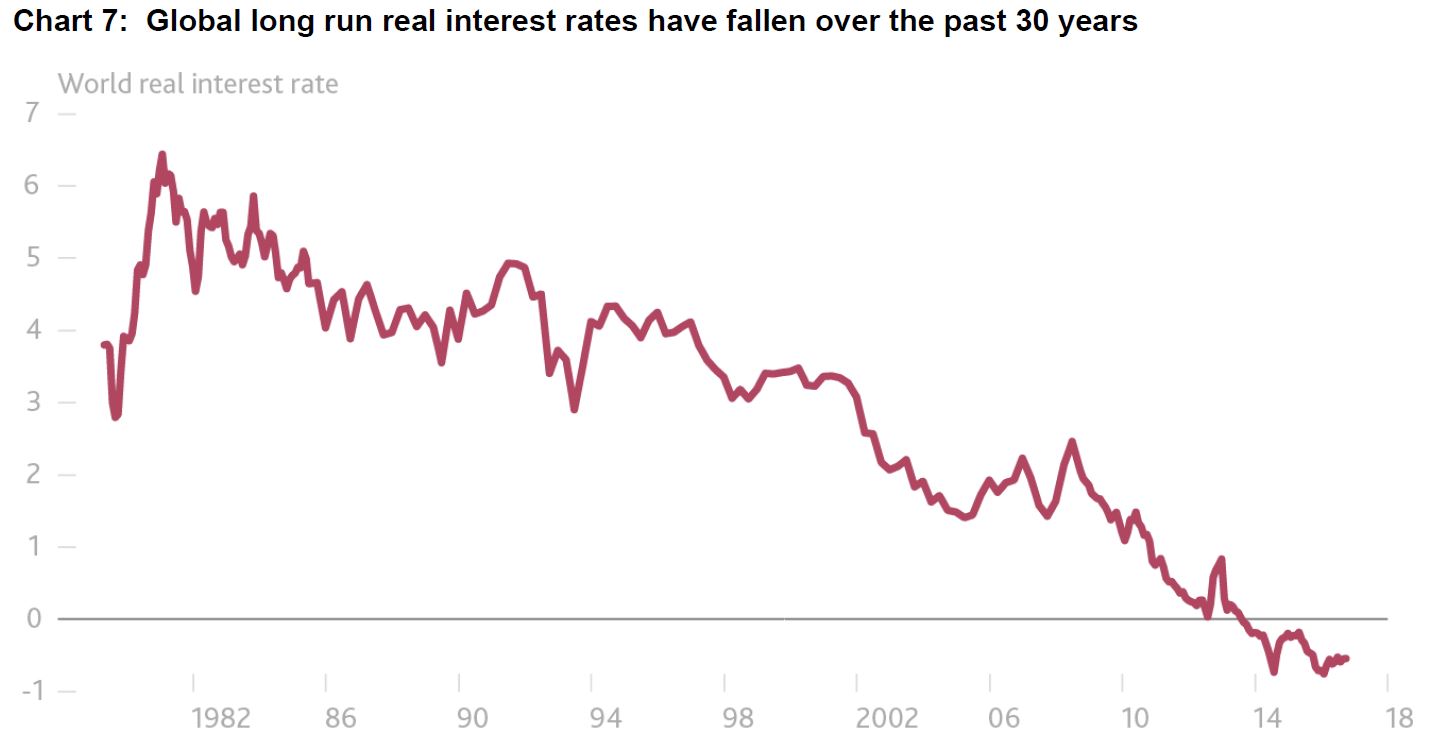

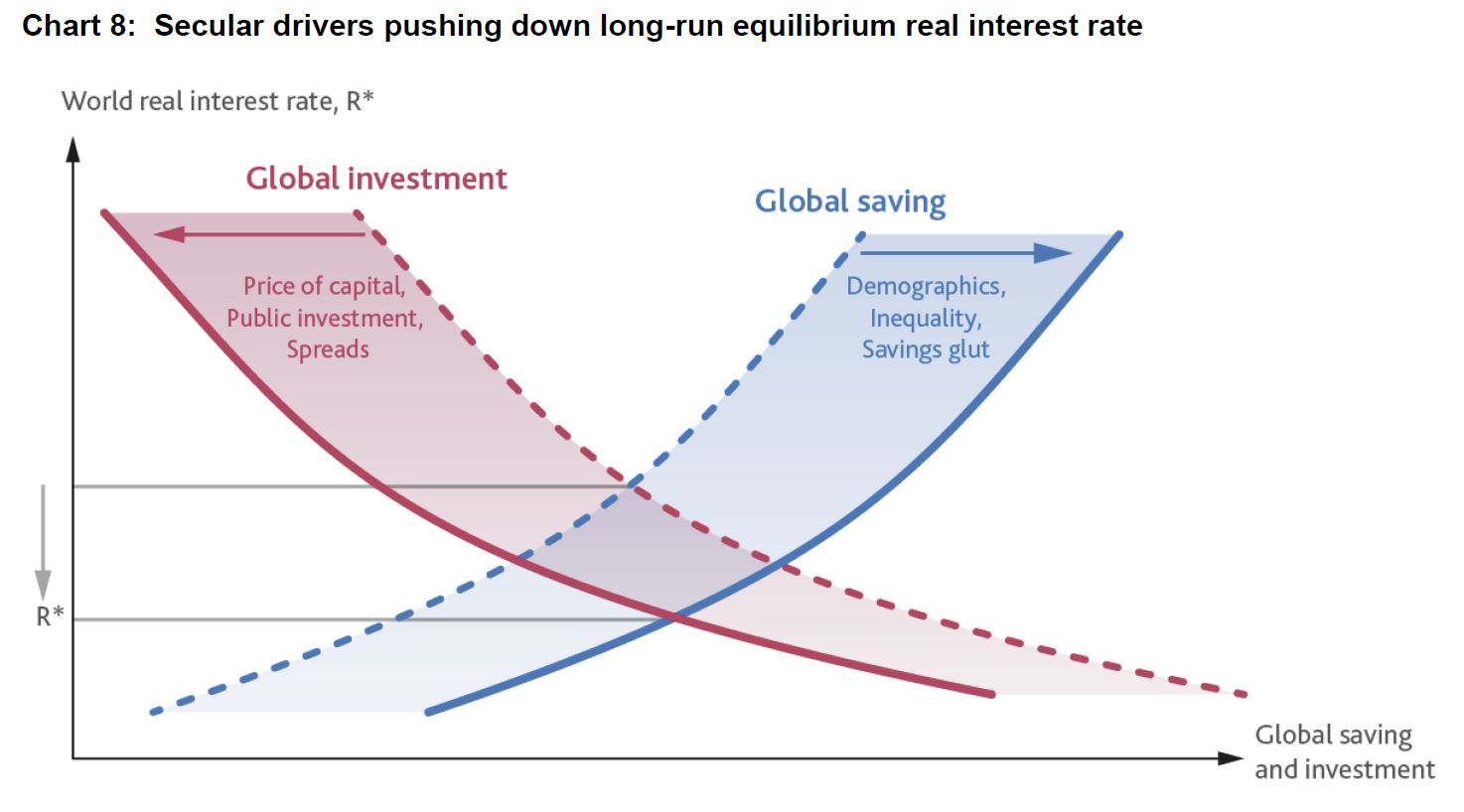

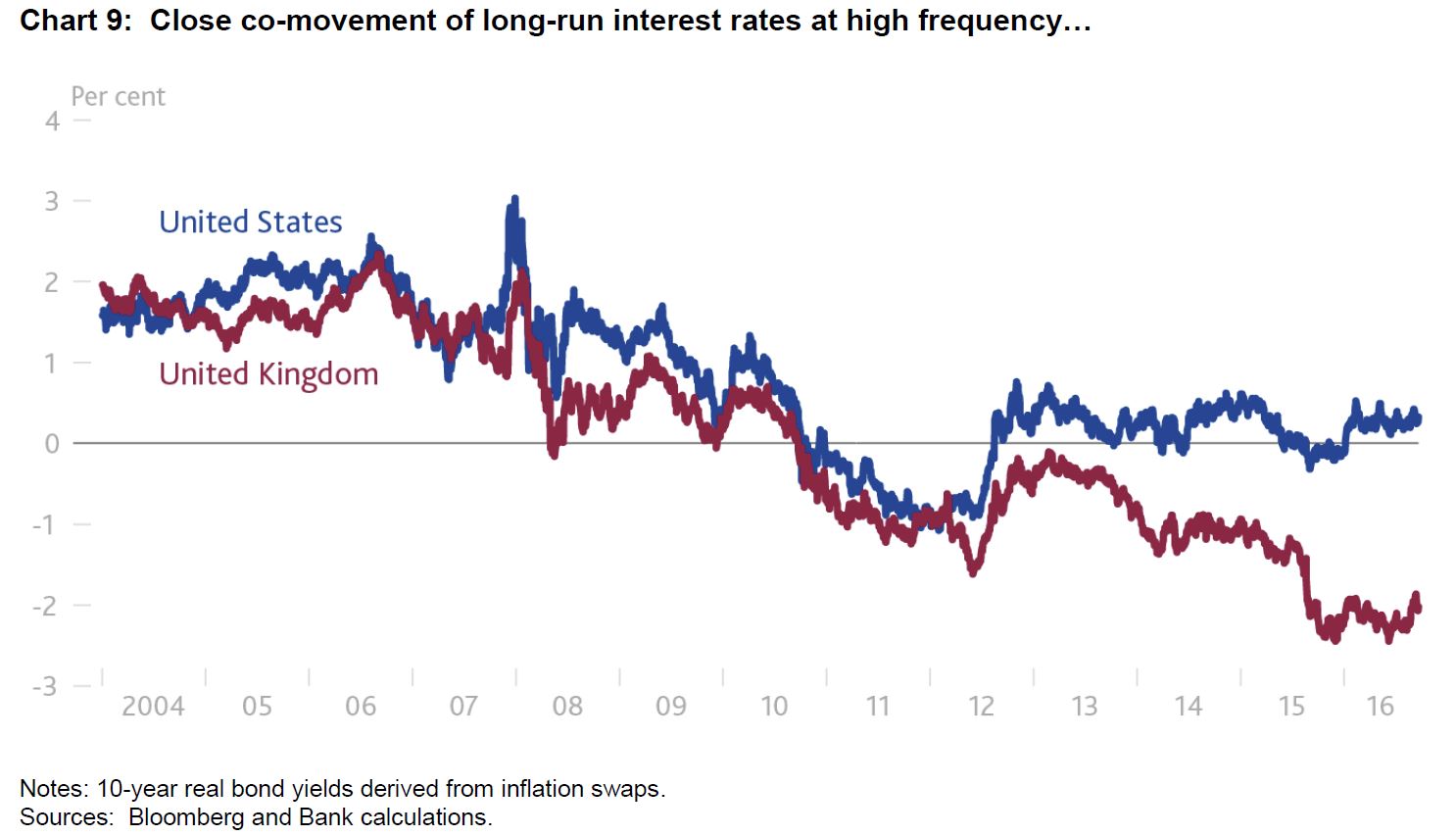

It is also worth saying the Bank of England has now signalled that the UK cash rate will rise, and this follows recent statements from the FED in the same vein. It is increasingly clear these moves to lift rates will raise international funding costs to banks and put more pressure on the RBA to follow suit.

Meantime, lenders continue to tighten their underwriting standards.

ANZ announced that it will be implementing new restrictions on some loans for residential apartments, units and flats in Brisbane and Perth. Now there will be a maximum 80 per cent loan-to-value ratio for owner-occupier and investment loans for all apartments in certain inner-city post codes. We think these changes reflect concerns about elevated risks, due to oversupply and price falls. ANZ’s policy changes apply to all apartments in affected postcodes, including off-the-plan and non-standard small residential properties valued at less than $3 million. Granny flats though are excluded.

More generally, ANZ also issued a Customer Interview Guide with specific which topics brokers should discuss with home and investment loan borrowers. “We expect brokers to use a customer interview guide (CIG) to record customer conversations as a minimum moving forward,” noted ANZ “while it is not required to submit the CIG with the application, it should be made available when requested as a part of the qualitative file reviews.”

CBA launched an interest-only simulator to help brokers show customers the differences between IO and P&I repayments and a new compulsory Customer Acknowledgement form to be submitted with all home loan applications that have interest-only payments to ensure that IO payments meet customer needs. CBA said that brokers must complete the simulator for all customers who are considering IO payments irrespective of whether the customer chooses to proceed with them. These requirements will be mandatory for all brokers and will become effective on Monday, 9 October.

Suncorp announced it is introducing new pricing methodology for interest only home lending. Variable interest rates on existing owner-occupier interest only rates will increase by 0.10% p.a and variable interest rates on all investor interest only rates will increase 0.38% p.a., effective 1 November, 2017.

But what about property demand and supply?

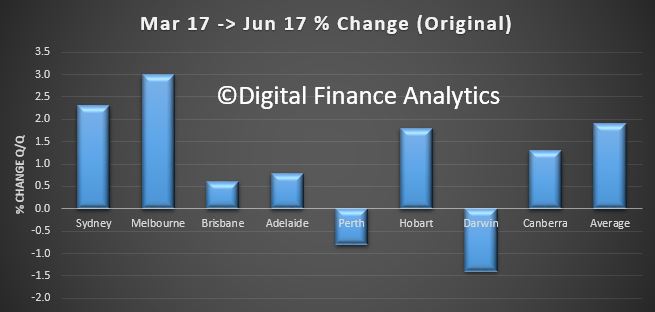

The ABS said Australia’s population grew by 1.6% during the year ended 31 March 2017. Natural increase and Net Overseas contributed 36.6% and 59.6% respectively. In fact, all states and territories recorded positive population growth in the year ended 31 March 2017, but Victoria recorded the highest growth rate at 2.4%. and The Northern Territory recorded the lowest growth rate at 0.1%. Significantly, Victoria, the state with the highest growth rate is currently seeing the strongest auction clearance rates, strong demand, and home price growth. This is not a surprise, given the high migration and this may put a floor on potential property price falls.

On the other hand, we also see an imbalance between those seeking to Trade up and those looking to Trade down, according to our research. Those trading up are driven by expectations of greater capital growth (42%), for more space (27%), life-style change (14%) and job change (11%). Those seeking to trade down are driven by the desire to release capital for retirement (37%), to move to a place which is more convenient (either location, or for easier maintenance) (31%), or a desire to switch to, or invest in an investment property (18%). In the past we saw a relative balance between those seeking to trade up and those seeking to trade down, but this is now changing.

Intention to transact, highlights that relatively more down traders are expecting to transact in the next year, compared with up traders. Given that there around 1.2 million Down Traders and around 800,000 Up Traders, we think there will be more seeking to sell, than buyers able to buy. As a result, this will provide a further drag on future price growth, especially in the middle and upper segments of the markets, where first time buyers are less likely to transact. This simple demand/supply curve provides another reason why prices may soon pass their peaks. Up Traders have more reason to delay, while Down Traders are seeking to extract capital, and as a result they have more of a burning platform.

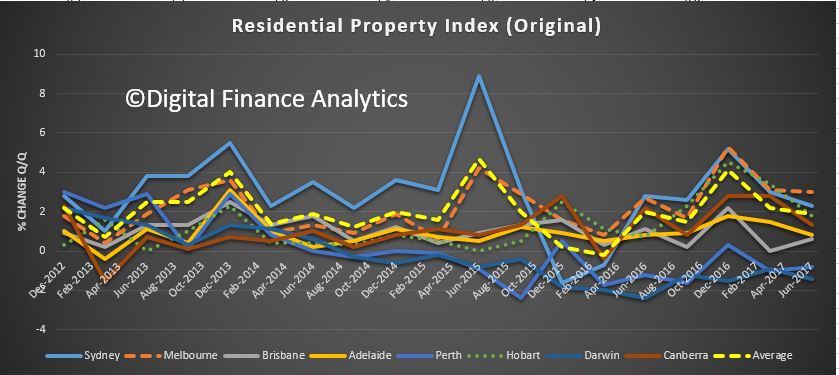

Finally, auction clearance rates were still quite firm, despite the fact that property price growth continues to ease and time on market indicators suggest a shift in the supply and demand drivers, especially in Sydney.

So, overall, banks are on one hand still wanting to grow their home loan portfolios (as it remains the main profit driver), but lending momentum is slowing, and underwriting standards are being tightened further, at a time when home price growth is slowing.

This leaves many households with loans now outside current lending criteria, households who are already feeling the pain of low income growth as costs rise. More households are falling into mortgage stress, and this will put further downward pressure on prices and demand.

So we think the risks in the mortgage market are extending further, and the problem is that recent moves to ease momentum have come too late to assist those with large loans relative to income. As a result, when rates rise, as they will, the pain will only increase further.

And that’s the Property Imperative weekly to 30th September 2017.