The Reserve Bank held the cash rate, more banks hiked mortgage interest rates, household debt rose again and our latest research showed that more than 800,000 households across Australia are experiencing mortgage stress. Welcome to the latest edition of the Property Imperative Weekly.

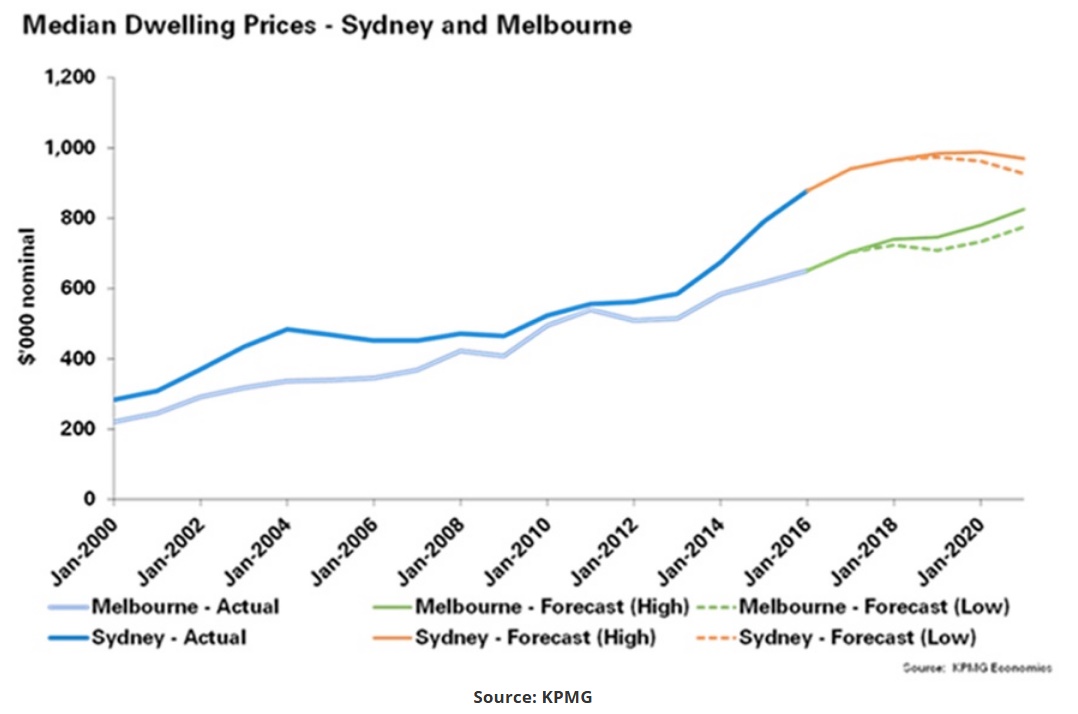

HSBC said the housing bubble fears were overblown. At a national level, a key reason for rising housing prices has been housing under-supply, Chief Economist Paul Bloxham wrote in a research note on Thursday and suggested that a significant fall in Australian housing prices, as occurred in the U.S. and Spain during the global financial crisis, is unlikely.

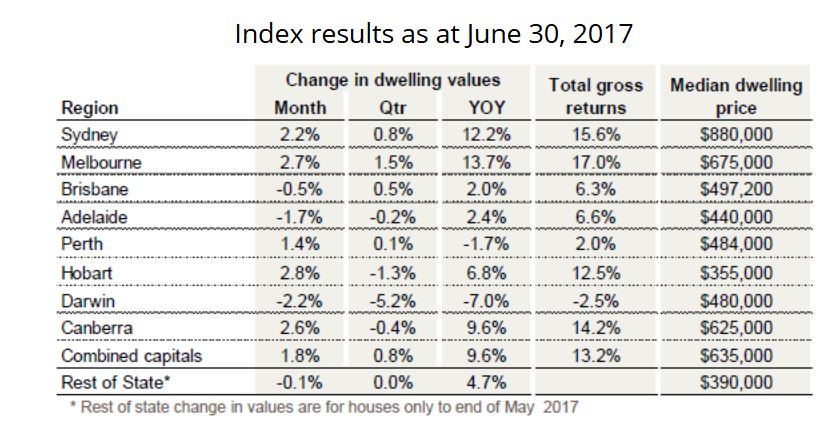

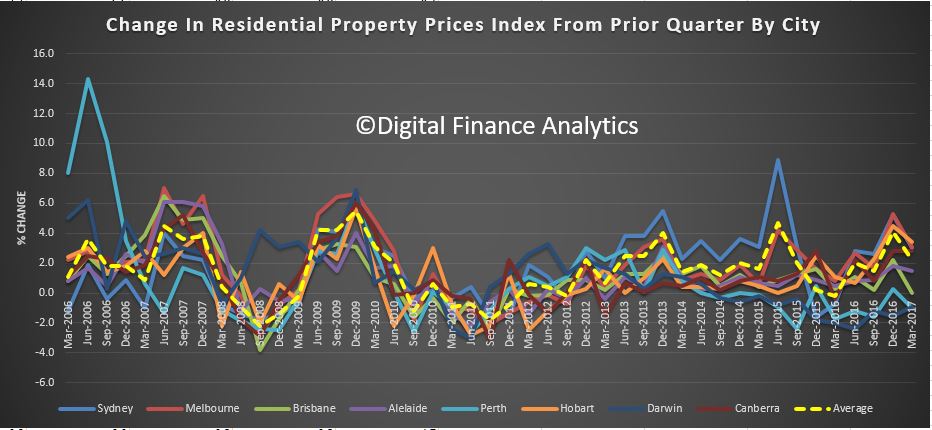

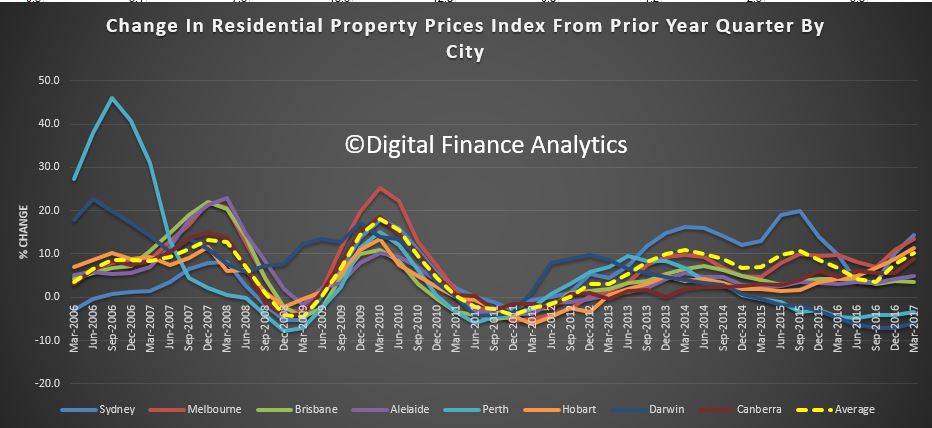

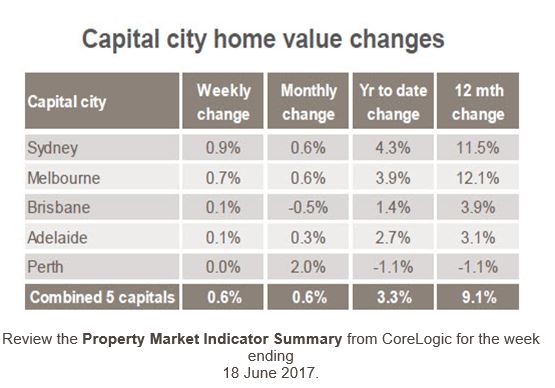

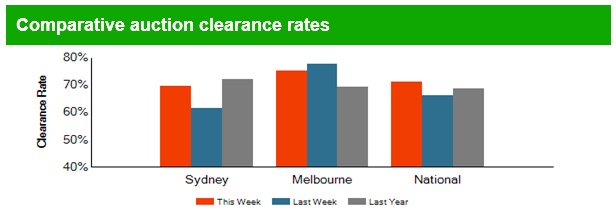

But data from CoreLogic showed whilst home prices rose in the last quarter, whilst auction volumes fell, and housing affordability deteriorated. The national price to income ratio was recorded at 7.3 compared to 7.2 a year earlier, and 6.1 a decade ago. It would have taken 1.5 years of gross annual household income for a deposit nationally at the end of the March compared to 1.4 years a year earlier and 1.2 years a decade ago. The discounted variable mortgage rate for owner occupiers was 4.55% and an average mortgage required 38.9% of a household’s income.

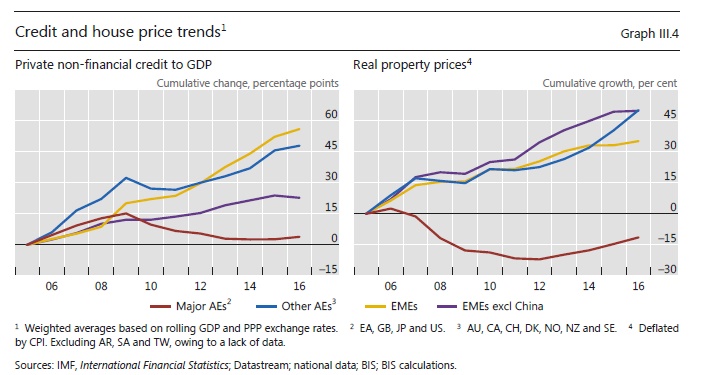

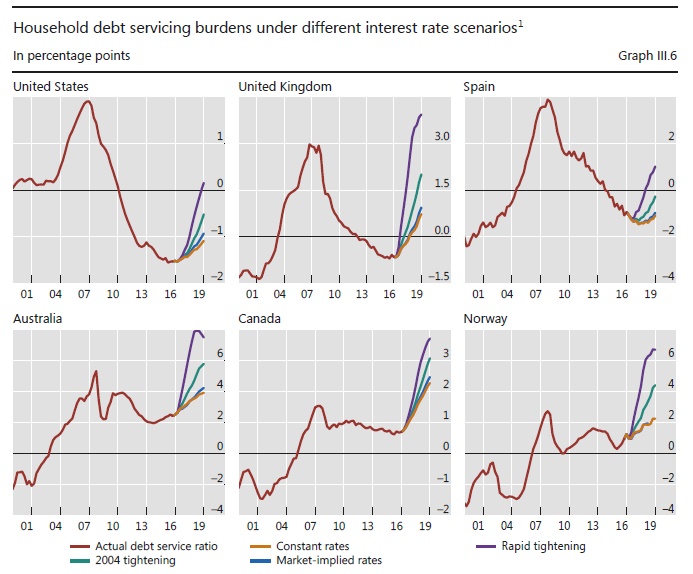

New data from the RBA showed that the household debt to income rose to a high of 190.4. Households are more in debt than they have ever been, and the main question has to be, can it all be repaid down the track, before mortgage interest rates rise so high that more get into difficulty.

Our June mortgage stress results showed that across the nation, more than 810,000 households are estimated to be now in mortgage stress up from 794,000 last month, with 29,000 of these in severe stress. This equates to 25.4% of households, up from 24.8% last month. We also estimate that nearly 55,000 households risk default in the next 12 months. The main drivers are rising mortgage rates and living costs whilst real incomes continue to fall and underemployment is on the rise. This is a deadly combination and is touching households across the country, not just in the mortgage belts.

We analyse household cash flow based on real incomes, outgoings and mortgage repayments. Households are “stressed” when income does not cover ongoing costs, rather than identifying a set proportion of income, (such as 30%) going on the mortgage. Stressed households are less likely to spend at the shops, which acts as a drag anchor on future growth. The number of households impacted are economically significant, especially as household debt continues to climb to new record levels.

Census data shows that Home ownership has continued to fall among younger Australians. Only 36 per cent of people aged 25-29 said they owned their home outright or with a mortgage – likely the lowest level since at least the 1960s. Home ownership for the next age group, 30-34, also declined, to 49 per cent, which is likely another record low.

Overall inequality in Australia is rising, between those who have property and those who do not. Australia has prominent examples of economic policies that disproportionately benefit the upper-middle class, such as the capital gains tax discount and superannuation tax incentives. We also have a geographically concentrated income distribution, with the rich living in neighbourhoods with other rich people. The poor are also more likely to live in close proximity to people who share their disadvantage.

There were major changes to mortgage rates and underwriting standards this week, with many following the herd by lifting rates for interest only borrowers, especially investors whilst making small downward movements in principal and interest loan rates, especially at lower LVRs.

NAB will start automatically rejecting customers who want to borrow a high multiple of their income and only pay interest on their home loan, amid concerns over the growing risks created by rising household indebtedness. While NAB already calculates loan-to-income ratios when assessing loans, it has not previously used the metric to determine whether a customer gets a loan, and such a blanket approach is unusual in the industry.

We have maintained for some time that LTI is an important measure. It should be use more widely in Australia, as it is a better indicator of risk than LVR (especially in a rising market).

Several more banks tweaked their mortgage rates this week. Virgin Money for example increased its variable and fixed rates for new owner occupied loans for LVRs of over 90% by 35 basis points or 0.35%, and increased its standard variable rates for owner occupied and investment interest online loans by 25 basis points.

Auswide Bank announced an increase to their reference rates for investment home loans and lines of credit of 25 basis points from 11 July 2017 will result in a new standard variable rate (SVR) of 6.10%. They blamed funding pressures and regulatory limits on investment and interest only lending.

ING Direct changed their reference rates, for owner-occupier borrowers, the principal and interest rates will decrease by 5 basis points. But for owner-occupier borrowers, interest-only rates will increase by 20 basis points and investor borrowers on interest-only loans will cop a 35 basis point rise. They are also encouraging borrowers to switch to principal and interest repayment loans.

Bendigo Bank lifted variable interest rates by 30 basis points for existing owner occupied interest only customers and 40 basis points for existing investment interest only customers. They also lifted business loans with new business interest only variable rates up by 40 to 80 basis points and fixed interest only rates increasing by 10 to 40 basis points. On the other hand, new Business Investment P&I variable rates will decrease by 15 basis points and fixed P&I interest rates decreased by 30 basis points.

The RBA held the official cash rate at 1.5 per cent for the tenth time on Tuesday. It hasn’t moved since a 25 basis point cut in August 2016. But Analysis shows that the gap between the RBA rate and the standard rate banks quote to mortgage borrowers is around the widest in 20 years. The Banks did not pass on the full benefit of the RBA’s record-low rates in order to offset costs and prop up profits. Last year there was a massive race to the bottom in terms of discounts to try to gain volume and share. Many banks dented their margins in the process. But now they’ve now got the perfect cover, thanks to APRA’s regulatory intervention, and so we expect to see mortgage rates continuing to grind higher, particularly for investors and anyone on interest-only. This will simply lead to more mortgage stress down the track whilst the banks rebuild their profit margins. Another example of inequality.

And that’s the Property Imperative to the 8th July. Check back again next week