The most popular government policy at the moment for solving housing affordability continues to be increasing housing supply. After a visit to the UK to look at this very problem, Treasurer Scott Morrison said:

The issue here fundamentally is about supply.

And it’s little wonder the government dwells so much on this argument. Rising house prices are very popular amongst Australian households, the majority of which are owners. And stamp duties on housing transactions are key sources of income for state governments. Our research found the default position for politicians is to sound concerned about housing affordability, but do nothing.

The supply refrain has all the hallmarks of a good policy for a politician. Increasing housing supply – rather than reducing the tax breaks that stimulate excessive demand – is a popular policy with peak property groups. The Property Council has been saying the same thing for years, so the supply solution has come to sound like fact.

The supply refrain has all the hallmarks of a good policy for a politician. Increasing housing supply – rather than reducing the tax breaks that stimulate excessive demand – is a popular policy with peak property groups. The Property Council has been saying the same thing for years, so the supply solution has come to sound like fact.

If the supply doesn’t flow or, as is occurring now, doesn’t cool prices, the federal government can blame the states for sluggish planning and land supply without having to put their money where their mouth is. States in turn can blame recalcitrant local governments for blocking housing development and “gold-plating” infrastructure requirements. Since the private sector almost wholly funds and delivers new housing, calling for more of it has been a pretty cheap strategy for government.

It’s true that increasing the supply of new homes in line with population and economic growth is a fundamental part of maintaining a healthy housing system. But to tout new housing production as the only policy lever without examining the question of demand is clearly an ineffective policy position.

The supply argument sounds believable – increasing supply will actually reduce prices in markets for most types of goods, like bananas, cars or televisions. Unfortunately, the housing market is different.

Why are housing markets different?

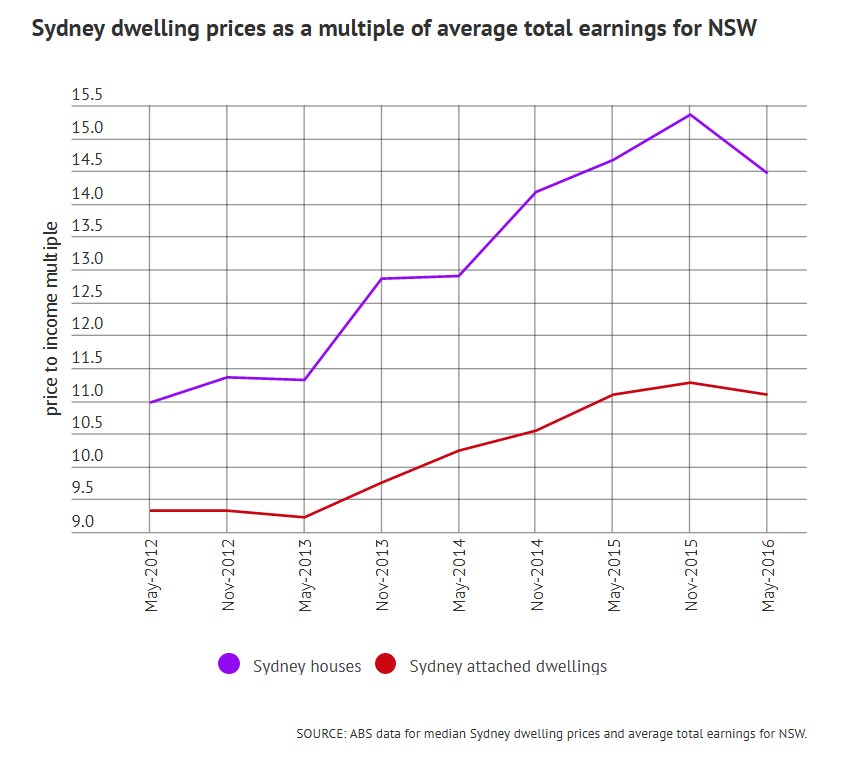

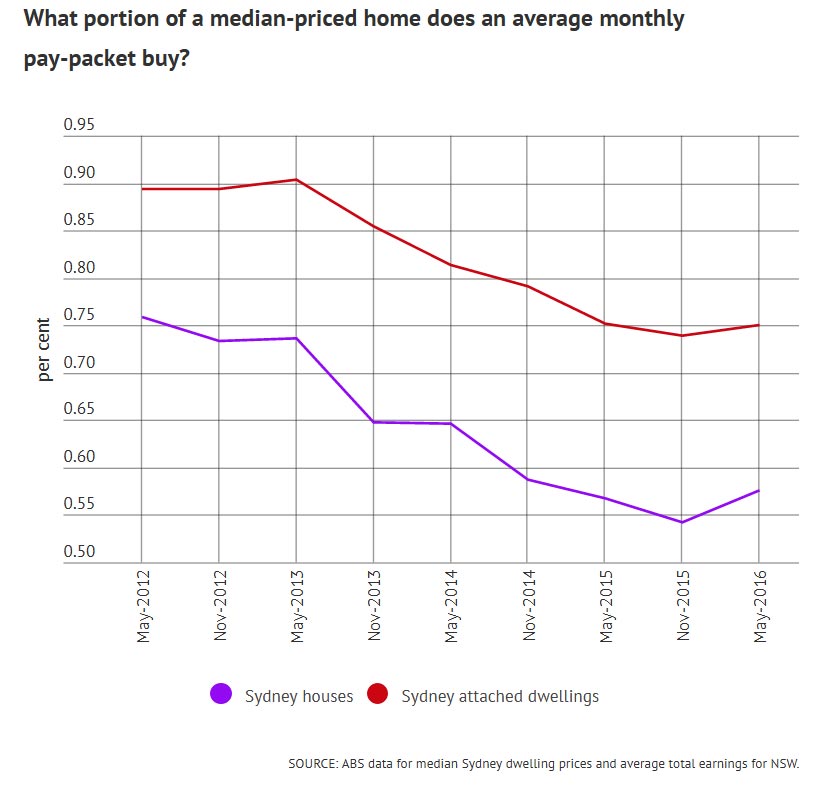

So why is it that despite record supply levels in Australia in recent years, prices have continued to rise in Sydney and Melbourne? We think there are a number of reasons.

New supply is a small fraction of the total stock of dwellings (about 2% in Australia). Prices are set by the total housing market – most of which already exists in the form of established homes.

Also housing is an unusual good in that as prices increase, demand in the short term actually increases (it’s an asset market). This makes it much more difficult for supply increases to reduce prices.

Increasing prices feeds demand

In most other markets increasing prices both encourage extra supply and reduce demand, so these two key forces are working together – prices in these markets come down sharply when supply increases. In housing markets these two forces are working against each other – the growth of investor demand is simply swamping new supply.

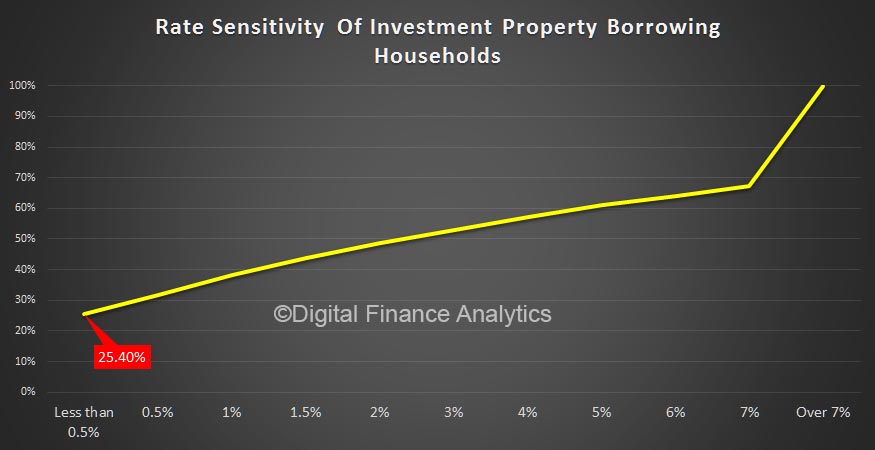

The very low interest rates on offer at the moment are exacerbating this trend.

Developers manage supply

Developers, and the banks that fund development, simply won’t allow supply to get ahead of demand in a way that would put significant downward pressure on prices. Dwelling approvals in Sydney and Melbourne are running way ahead of building starts, but housing projects are released in stages to avoid swamping the market. Since our major banks have the majority of their loan books in retail mortgages, it’s no wonder they avoid funding enough supply to increase their own risk levels.

How much new supply would improve affordability anyway?

Even if Australia’s developers and financiers were less cautious, it’s probably not feasible to produce enough supply to really knock prices around when demand is very strong.

For example, prior to the global financial crisis, Ireland – which is about the same size as Sydney, increased supply to 90,000 dwellings per year (Sydney does about 30,000 dwellings per year) and prices still kept rising. It wasn’t the over-supply of homes that caused Irish house prices to fall dramatically but rather the sudden contraction of demand when the global financial crisis hit.

Under more stable conditions, the problem of generating additional housing supply remains. Australia’s prime minister has encouraged the states to fix their planning laws to make it easier get housing approvals and building to flow.

But there has been a continuous wave of planning reform over the last 10 years in Australia, and Sydney and Melbourne dwelling approvals are at long-term highs. For example, in 2015-16, Sydney recorded over 56,000 new dwelling approvals and Melbourne over 57,000.

In fact, approvals are running at about double the actual dwelling construction levels, so “fixing” the planning system is unlikely to have much impact on dwelling supply levels.

High-density supply fuels land speculation

Much new supply is in apartments. In the rush to create new supply, some local councils and state governments have provided bonuses to developers by allowing, at no charge, more apartments on a site. Land owners have seen this behaviour and are likely to increase land prices on the assumption that this will always happen. So, in this case, more supply (through additional apartments) may have actually increased prices not reduced them.

The global ‘financialisation’ of housing

Demand has increased because the focus for many housing investors is now not the cash flow generated by rents but the value of a house as a financial product. For example, at the moment there is continued strong demand for housing by investors despite the fact that apartment rents have started to decrease in Sydney and are flat in Melbourne.

The internet, and the global real estate market it helps support, enables national and international investors to be an increasingly important part of the market. They increase demand pressures in the best-performing (in terms of price growth) cities of Sydney and Melbourne by “soaking” up the new supply.

If politicians were serious about the affordability crisis, they would be trying to support the important but underfunded affordable housing sector. Better targeting tax breaks towards new and affordable rental housing, rather than fuelling demand for existing homes, would also help. But until our politicians can see past supply slogans we can expect very little policy change.

Authors: Chair of Urban Planning and Policy, University of Sydney; Professor – Urban and Regional Planning, University of Sydney

Source: Roy Morgan Research Single Source: Mortgage holders 12 months to October 2015 (n=11,249); 12 months to October 2016 (n=10,655).

Source: Roy Morgan Research Single Source: Mortgage holders 12 months to October 2015 (n=11,249); 12 months to October 2016 (n=10,655). Source: Roy Morgan Research Single Source; Mortgage holders 12 months to October 2016 (n=10,655).

Source: Roy Morgan Research Single Source; Mortgage holders 12 months to October 2016 (n=10,655).