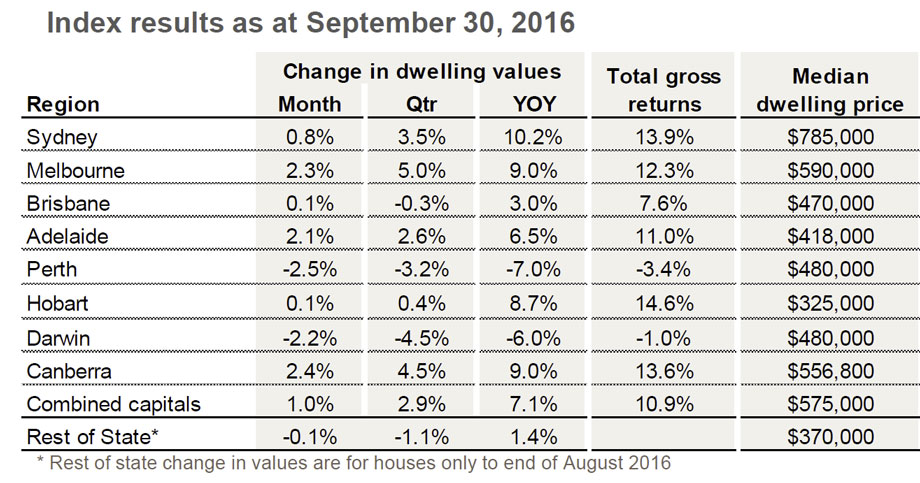

Talking about average home price growth is rarely helpful, it is important to get granular. So CoreLogic’s post on real home price growth by major centres is very helpful because it corrects growth for inflation. Their analysis shows that real home values are now more than 20% lower than their peak in Perth and Darwin, but well up in Sydney. Over the longer term, Sydney and Melbourne are the only two capital cities in which real home values are now back above their previous peaks. We have a multi-speed market.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released consumer price index (CPI) data for the September 2016 quarter earlier this week. According to the data, headline inflation increased by 0.7% over the quarter to be 1.3% higher over the year. Meanwhile, underlying inflation was recorded at 0.3% over the quarter and 1.5% higher over the past 12 months. Both headline and underlying inflation have increased at a rate below the RBAs target range of 2% to 3%. This would usually see the RBA cut interest rates to try and lift inflation however, the previous cuts in May and August, which had the same intent, have not successfully lifted inflation. What those cuts did manage to do was re-energise growth in housing, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne. For this reason there is some speculation as to whether the RBA will risk cutting interest rates again given concerns that a lower cash rate will fail to push the dollar lower and lift inflation but add further heat to an already strong housing market.

With the CPI data released, we can pair it with the CoreLogic home value index data to September 2016, in order to obtain an understanding of real growth in values. Although headline value growth is lower than it was a year ago, so too is headline inflation which mean that real value growth, particularly in Sydney and Melbourne remains strong.

The above chart highlights the real and nominal changes in home values across each capital city over the 12 months to September 2016. In both real and nominal terms values have fallen over the past year in both Perth and Darwin while they have increased across each of the remaining capital cities. There’s also been evidence that along with Sydney and Melbourne, where growth has been strong for almost four years now, value growth has also picked up in other cities such as Adelaide, Hobart and Canberra.

If you look at the compound annual change in real home values over the past five, ten and 15 years, the 15 year time-frame in most capital city provides the strongest performance. The clear exception is in Sydney where the last five years have resulted in the strongest annual returns. In contrast, across all other capital cities except for Perth and Hobart the past five years have recorded the weakest annual growth across each of the three time-frame. This result really highlights the strength of the Sydney market over the past five years and its relative weakness over the 10 years preceding.

Since the end of 2008 (ie post GFC), growth in home values has significantly skewed towards the Sydney and Melbourne housing markets. As highlighted in the above chart, when adjusted for inflation values are lower that they were at the end of 2008 in Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth, Hobart and Darwin. Sydney and Melbourne have also seen a substantially greater increase in values relative to Canberra which was the only other capital city to have seen an increase in real home values.

Sydney and Melbourne are the only two capital cities in which real home values are now back above their previous peaks. After peaking all the way back in the March 2004 quarter, real home values in Sydney are now 35.3% higher in Sydney and in Melbourne they are 17.2% higher than their September 2010 peak. All other capital cities are still recording real home values below their previous peaks. The magnitude of these declines are recorded at: -10.2% in Brisbane, -5.3% in Adelaide, -20.2% in Perth, -15.6% in Hobart, -23.8% in Darwin and -1.0% in Canberra. In some of these cities, values peaked many years ago, as far back as 2007 in Perth and Hobart and 2008 in Brisbane.

Although interest rates are low and in real terms homes have been becoming more affordable outside of Sydney and Melbourne it still hasn’t proved to be enough to lure substantial demand and subsequent growth across the other capital cities. What this highlights is the importance of employment, what sets Sydney and Melbourne apart, outside of more expensive housing prices, is the fact that they both have strong economies which are creating jobs. Housing affordability alone is no longer enough to attract an increasing level of housing demand, you need a strong economy and the jobs that go along with those strong economic conditions.

Perth and Darwin in particular are well into a fairly substantial value decline phase which is appears set to continue. Since their respective market peaks in September 2007 and September 2010, real home values are now -20.2% and -23.8% lower respectively.