The 2016 Demographia survey (the 12th edition) is out using data from Q3 2015. Once again Australians are shown to be exposed to highly unafforable housing, with all the downstream economic consequences which follow. Policy, regulation, and vision have all failed us. Whilst inflated prices bloat banks’ balance sheets thanks to massive lending for housing, the economic outcomes are disastrous. The resulting stagnation or even decline in household discretionary incomes is at least as much a threat to prosperity and job creation as the limited gross income gains.

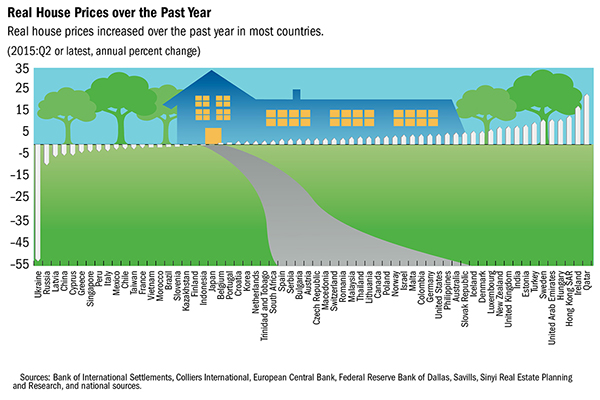

” Australia had 33 severely unaffordable markets, followed by the United States with 29 and the United Kingdom with 17. New Zealand and Canada each had six severely unaffordable markets, while China’s one market (Hong Kong) was also severely unaffordable.”

The survey covers 367 metropolitan markets in nine countries (Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the United States). A total of 87 major metropolitan markets — with more than 1,000,000 population — are included, including five megacities (Tokyo-Yokohama, New York, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Los Angeles, and London).

The survey covers 367 metropolitan markets in nine countries (Australia, Canada, China, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, Singapore, the United Kingdom and the United States). A total of 87 major metropolitan markets — with more than 1,000,000 population — are included, including five megacities (Tokyo-Yokohama, New York, Osaka-Kobe-Kyoto, Los Angeles, and London).

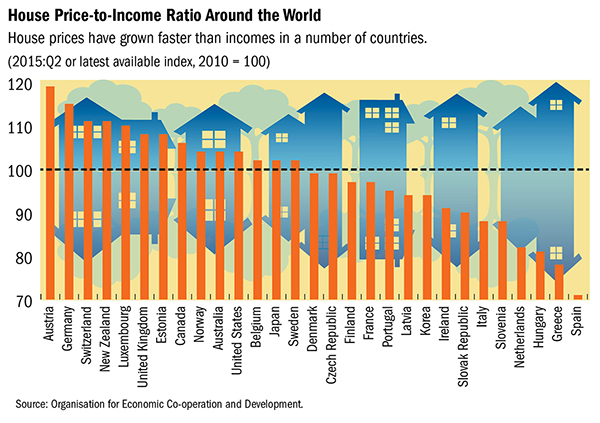

The Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey rates middle-income housing affordability using the Median Multiple.” The Median Multiple is widely used for evaluating urban markets, and has been recommended by the World Bank and the United Nations and is used by the Joint Center for Housing Studies, Harvard University. The Median Multiple and other similar price-to-income multiples (housing affordability multiples) are used to compare housing affordability between markets by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the International Monetary Fund, The Economist, and other organizations.

Demographia uses the following housing affordability ratings:

- Severely Unaffordable 5.1 & Over

- Seriously Unaffordable 4.1 to 5.0

- Moderately Unaffordable 3.1 to 4.0

- Affordable 3.0 & Under

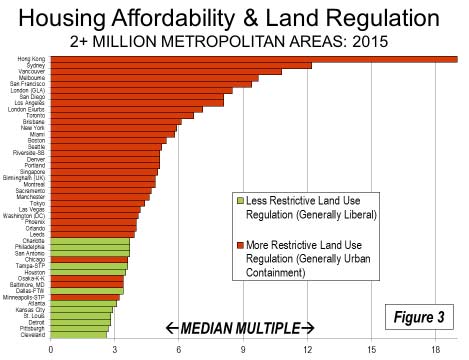

Hong Kong’s Median Multiple of 19.0 was the highest recorded (least affordable) in the 12 years of the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. Sydney was the second least affordable major market, with a Median Multiple of 12.2. Sydney’s increase of 2.4 points from its 9.8 Median Multiple in 2014 is the largest year-to-year deterioration ever indicated in the 12 years of the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey. It is also highest Median Multiple outside Hong Kong in the history of the Survey, exceeding the extremes experienced on the US West Coast during the housing bubble of the last decade. Vancouver was the third least affordable major market, with a Median Multiple of 10.8. Auckland, Melbourne and San Jose all had Median Multiples of 9.7. They were followed by San Francisco at 9.4, and London (Greater London Authority), at 8.5. Two other markets had Median Multiples of 8.0 or above, including San Diego and Los Angeles, both at 8.1.

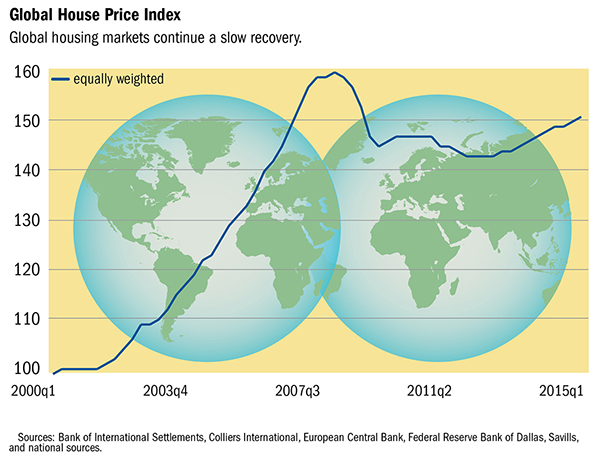

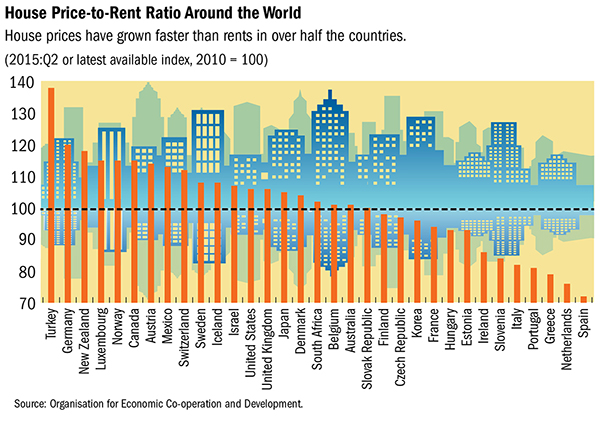

Virtually all governments consider household economic issues as a top priority, especially increasing the standard of living and reducing or eradicating poverty. Yet economic growth has been laggard, and discretionary income trends are even more concerning. Housing costs, which represent the largest household expenditure category, have been rising much faster than incomes. The resulting stagnation or even decline in household discretionary incomes is at least as much a threat to prosperity and job creation as the limited gross income gains.

The largest losses in housing affordability have been associated with urban containment policy. Severely unaffordable housing (Median Multiple of 5.1 or higher) has occurred only in major metropolitan areas that have strong land use policy, especially urban containment boundaries and variations thereof. Corrective measures that could halt or reverse losses in housing affordability from urban containment policy have either been absent or not been implemented. As a result, urban containment policy has been a profound policy failure, as house prices have doubled and tripled relative to incomes in many metropolitan areas.

In the introduction, Senator Bob Day says:

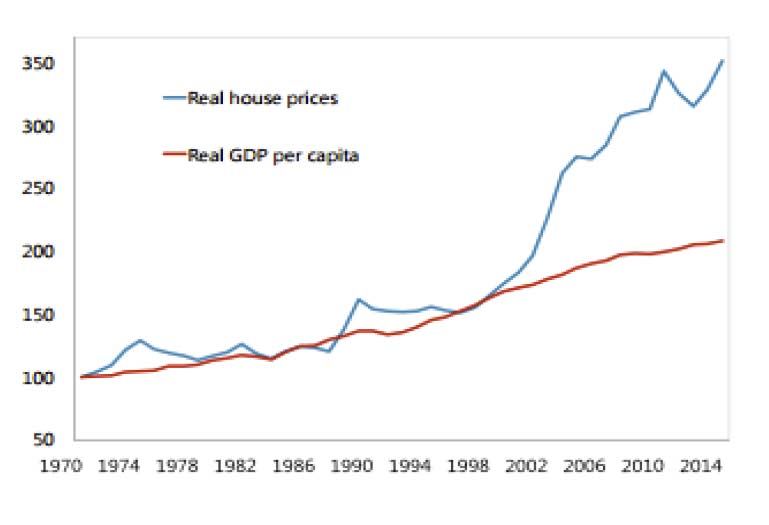

For more than 100 years the average Australian family was able to buy its first home on one wage. The median house price was around three times the median income allowing young home buyers easy entry into the housing market As can be seen from the graph below (“ Real Home Price Index”), the median house price has increased, in real terms, by more than 300% – from an average index of 100 between 1900 and 2000 to an index over 300 by the year 2008.

Relative to incomes, house prices have increased from three times median income to more than nine times income. That’s $600,000 they are not able to spend on other things – clothes, cars, furniture, appliances, travel, movies, restaurants, the theatre, children’s education, charities and many other discretionary purchase options.

It is a similar story in the UK, US, Canada, New Zealand, Ireland and Japan.

The economic consequences of this change have been devastating. The capital structure of these countries’ economies have been distorted to the tune of hundreds of billions of dollars and for those on middle and low incomes the prospect of ever becoming homeowners has now all but vanished. Housing starts are below what they should be and so have all the jobs associated with them – civil construction, house construction, transport, appliances, soft furnishings, you name it. Not to mention billions of dollars in lost taxes and other housing-related revenue to the nation state.

The distortion in the housing market, this misallocation of resources resulting from the supply-demand imbalance is enormous by any measure and affects every other area of a country’s economy. New home owners pay a much higher percentage of their income on house payments than they should. Similarly, renters are paying increased rental costs reflective of the higher capital and financing costs in turn paid by landlords.

Economies have been distorted and getting them back into alignment is going to take some time. But it is a realignment that is necessary. A terrible mistake was made and it needs to be corrected.