The most common products provided by life insurers are death cover, total permanent disability (TPD), trauma, and income protection. Annuities are also provided by some insurers.

- Life Insurance Death Cover pays a lump sum to the policy owner. If the policy owner and the life insured are one and the same then often beneficiaries would be a partner or child upon the death of the life insured. In some cases, a terminal illness benefit may be available and is an advancement of the death cover paid if the insured is medically certified as being terminally ill within a defined period (usually 12 or 24 months).

- Total Permanent Disability – known as TPD – pays a lump sum if the insured becomes totally and permanently disabled.

- Trauma provides payment if the insured person is diagnosed with a specified illness or injury. These policies include the major illnesses or injuries that will make a significant impact on a person’s life, such as cancer or a stroke.

- Income Protection replaces the income lost due to a person’s temporary inability to work due to injury or sickness. Sometimes also referred to as disability income insurance or salary continuance insurance.

- Annuity: An investment product providing a guaranteed income for either a fixed term or the lifetime of the policy holder.

Life insurance business can be divided into three groups according to the type of policyholder.

- Individual risk insurance: This insurance is sold to the final consumer directly or via a financial advisor. Individual consumers can choose whether to hold one or a range of life products listed above. The Life Insurance Act contains specific restrictions that significantly limit the ability of the life company to re-price the policy or change its terms and conditions. The policy holder is entitled to a guaranteed renewal of their policy.

- Group risk insurance: This insurance is sold to superannuation funds to provide cover to their members. Group insurers provide a default level of automatic cover, usually including TPD and death cover and sometimes income protection cover, to the trustee. The policyholder is the trustee of the fund who contracts the insurance on behalf of the membership. The terms, conditions and pricing of the policy are typically periodically re-negotiated periodically between the insurer and the trustee.

- Reinsurance: is insurance that is purchased by an insurance company (the cedant) from one or more other insurance companies (the “reinsurer”) as a means of risk management. The cedant and the reinsurer enter into a reinsurance agreement which details the conditions upon which the reinsurer would pay a share of the claims incurred by the ceding company in exchange for a premium.

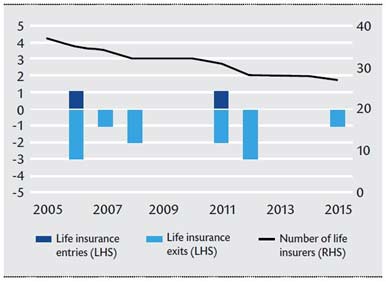

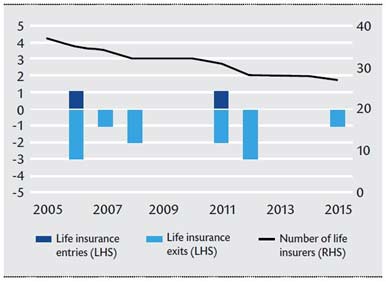

As at 20 August 2015, there were 28 authorised life insurance companies. Insurers are comprised of a number of distinct groups: 8 large diversified insurers, 4 insurance risk or annuity specialists, 9 relatively small or niche market players and 7 reinsurers. The number of life insurers has reduced in the past decade in a continuation of a steady trend that began around 1990, when the number of licences peaked at 61. Since that time, mutually-owned insurers – which were once the largest life insurers in the market – have largely disappeared, while the banking industry has developed a prominent role in the ownership of life insurance and wealth management businesses more generally.

Some reinsurers both reinsure and sell life insurance directly. Many large insurers that provide individual life policies also provide group insurance to superannuation fund trustees but there are a number of insurers that largely specialise in servicing the group insurance market. Most insurers offer both life lump sum (TPD and Death) and income protection policies.

Some reinsurers both reinsure and sell life insurance directly. Many large insurers that provide individual life policies also provide group insurance to superannuation fund trustees but there are a number of insurers that largely specialise in servicing the group insurance market. Most insurers offer both life lump sum (TPD and Death) and income protection policies.

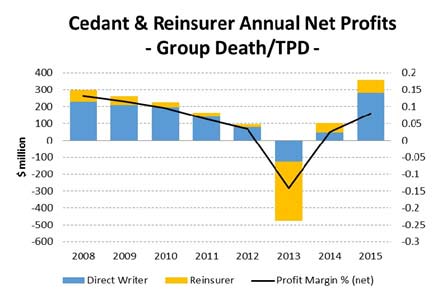

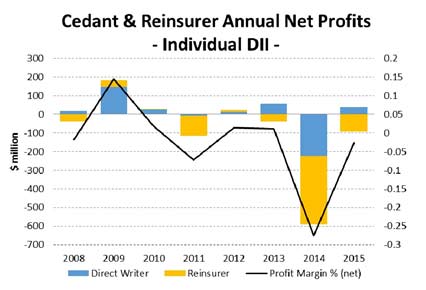

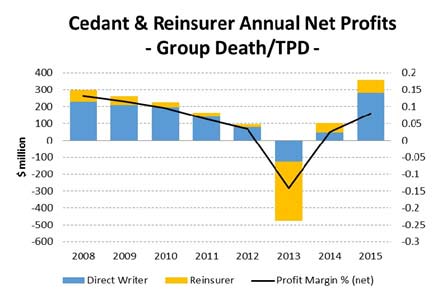

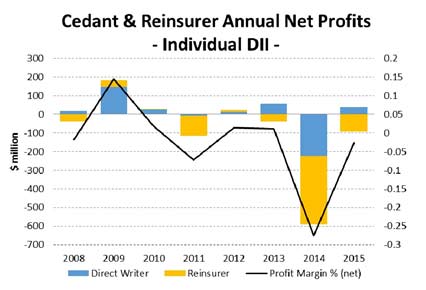

Although the life insurance industry continues to operate with an adequate excess of capital above minimum regulatory requirements, the profitability of the life insurance sector has been under strain in recent years. Weak profitability has been driven by, in particular, the mispricing of risk which resulted in losses for insurers during 2013-14:

- group risk insurers experienced higher-than-expected lump sum disablement (TPD) claims payouts which generated substantial losses in 2013, with some reinsurers being particularly affected; and

- individual disability income business was the most significant source of losses in 2014.

In addition to the issues above, the industry has had to deal with a challenging external environment, including ongoing financial market volatility, persistently low interest rates, and pressures on overall industry operating efficiency. Some insurers have managed these challenges better than others. In particular, those insurers with a strong risk management framework, an effective risk appetite statement and a robust approach to capital management have proven best able to manage and adapt to operating conditions.

Poor risk management over time led to claims payouts exceeded the premiums collected for group total disability and group income protection, lines of insurance during 2013 and individual total disability and life in 2014. Reinsurers provided reinsurance on generous terms to these insurers, in effect allowing poor underwriting and risk management practices. As a result, reinsurers bore most of the losses during this period.

This outcome is not sustainable in the long term. Consumers of long-term products such as life insurance are ultimately best served if insurers are financially sustainable, thereby enabling firms to deliver on their long-term promises. There were various reasons for losses including :

- underwriting and pricing practices in both the life insurance and reinsurance industry left both the direct and reinsurance market exposed to adverse movement in market conditions. In particular, thin margins were exposed by pricing that did not properly align with the policy benefits. A notable example was a trend whereby default coverage increased in group life schemes, but the underlying premium rates did not increase, and in many case fell, despite the increased exposure;

- decreases in global interest rates reduced investment returns;

- competitive tension in group life market tendering saw the process often weighted toward acquisition and retention of business rather than sustainability; and

- increased plaintiff solicitor involvement drove an increase in lump sum total permanent disability (TPD) claims. The resulting increase in claims has been seen, in part, as a correction of a rate of claims which may not have accurately reflected the industry’s underlying exposure. For instance, prior to targeted marketing by plaintiffs’ firms, individual members may not have been aware of their available cover. An increase in the number of TPD claims related to mental illness and other complicated injuries, and changing community standards as to what conditions give rise to claims, has also resulted in more claims payments and requires greater claims management and resourcing.

The reinsurers seem to have carried a disproportionate share of the losses. Reinsurers incurred more than half of the total group death and TPD losses in 2013. Followed by significant losses in 2014 for individual disability income. This raises the question about the nature of the reinsurance arrangement in place and the role reinsurers may have played in the poor overall performance.

Reinsurers sought to mitigate the adverse impact of the poor experience on their financial position by significantly reducing or even ceasing to write or tender for new business. This in turn lead to an increase in prices for policyholders and/or a tightening of coverage, where permitted, which has inevitably been passed on to policyholders. Changes made by insurers include:

Reinsurers sought to mitigate the adverse impact of the poor experience on their financial position by significantly reducing or even ceasing to write or tender for new business. This in turn lead to an increase in prices for policyholders and/or a tightening of coverage, where permitted, which has inevitably been passed on to policyholders. Changes made by insurers include:

- no longer making ‘opt-in’ offers that allow members to take or increase cover with little or no evidence of health status;

- increasing the length of the ‘at work’ period for members to become eligible for cover (e.g. from one day to one month);

- tightening the definition of TPD (for example, from ‘unlikely to work’ to ‘unable to work’);

- introducing severity-based TPD benefits;

- introducing TPD benefits payable via instalments rather than as a lump sum;

- reducing default TPD benefits and increasing default GSC benefits;

- reducing automatic acceptance limits;

- making greater use of health questions for optional cover; and

- making greater use of exclusions for pre-existing conditions, hazardous occupations, suicides and pandemics.

APRA has observed that many insurers chose to increase premiums to improve profitability. While some premium increase may be needed to ensure pricing is sustainable following a period in which premiums were insufficient to reflect risk, in APRA’s view, these increases do not by themselves address the structural reasons that led to the underlying problems and have produced an unexpected increase in the cost of insurance for superannuation fund members.

One area of potential change identified by APRA relevant to this Inquiry is the introduction of a mechanism to allow the rationalisation of legacy products to occur more easily. Legacy products arise particularly in life insurance and superannuation, where the financial products often last a lifetime, but the financial, legal and social environment continually changes. In addition, the life insurance sector has undergone a significant consolidation over the past 20 years, leading to many duplicated and outdated products. The industry is still grappling with the challenge of addressing those issues.

Life insurers regularly introduce new products to better reflect consumer demand and changed market conditions; while the previous products (legacy products) are typically no longer made available for new business. However, these legacy policies must continue to be administered in accordance with the original contract terms.

Over time, legacy products become more complex and expensive to administer and may no longer meet the requirements of the beneficiaries. Industry estimates suggest that approximately 25 per cent of all funds under management are in legacy products. The cost of these legacy products is ultimately borne by the policyholders.

As life insurance products involve a contract between the life insurer and the policyholder, terms cannot be unilaterally modified by either party to the contract. Consequently, it is very difficult to rationalise legacy products in the absence of a legislative mechanism, as each policyholder would need to consent to any changes. In the case of individual risk business, a policyholder may not be able switch to a newer product or provider readily, as their health status may have changed in the interim meaning that they either cannot obtain replacement insurance or can only do so at significantly increased cost.

There is a range of very complex legal, consumer and tax issues that arise if a life insurer seeks to move policyholders from a legacy product to a new product, restricting the ability of insurers to close legacy products. The benefits of a simpler, though still robust, mechanism to rationalise legacy financial products has been recognised for some time. The issue was, for example, a recommendation of the Report of the Taskforce on Reducing Regulatory Burdens on Business in 2006. As noted in the Financial System Inquiry Final Report, between 2007 and 2010 Government worked with industry to develop a mechanism to facilitate product rationalisation. However, such a mechanism was not finalised or implemented.

The mechanism would have facilitated rationalisation of genuine legacy products — that is, not simply those that are performing poorly — subject to a ‘no disadvantage test’ for relevant consumers. It would also have provided tax relief to ensure consumers were not disadvantaged as a result of triggering an early capital gains tax event.