Its crunch time in Australian banking, as property momentum slows, households feel the pinch and mortgage risks rise. Welcome to the Property Imperative Weekly to 4th November 2017.

Watch the video or read the transcript.

We start this week’s review by looking at interest rates. The Bank of England lifted their cash rate by 25 basis points, the first hike since July 2007. The move highlights how shrinking output gaps and tighter labour markets are pushing central banks towards interest rate normalisation. The FED kept US rates on hold at their November meeting, but signalled its intent to lift rates further, and Trump’s nomination for the FED Chair, Jay Powell to replace Yelland will probably not change this. The US economy is certainly outpacing Australia’s at the moment. Rates are indeed on the rise and policy makers are of the view that if there is the need to lift rates, the tightening should be gradual as to not destabilize the economy. The question is though whether this will neutralise the impact, or simply prolong the pain as we adjust to more normal rates. The boom brought about by the banks’ policy of extending credit must necessarily end sooner or later. RBA please note!

Turning to this week’s Australian economic data, Retail turnover was flat in September according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. More evidence that many households are under financial pressure. In trend terms, there were falls in WA, NT and ACT. NSW had a 0.1% rise compared to last month. On the other hand, Dwelling approvals were stronger than expected, up 1.8 per cent in September 2017, in trend terms, the eighth rise in a row. Approvals for private sector houses rose 0.7 per cent.

The latest credit data from the RBA showed housing lending grew the most, with overall lending for housing up 0.5% in September or 6.6% for the year, which is higher than the 6.4% the previous year. Looking at the adjusted RBA percentage changes we see that over the 12 months’ investor lending is still stronger than owner occupied lending, though both showed a slowing growth trend. They said $59 billion of loans have been switched from investment to owner occupied loans over the period of July 2015 to September 2017, of which $1.4 billion occurred in September 2017. So more noise in the numbers!

Unusually, personal credit rose slightly in the month though down 1.0 % in the past year. Lending to business rose just 0.1% to 4.3% for the year, which is down from 4.8% the previous year. Business investment (or the lack of it), is a real problem. As John Fraser, Secretary to the Treasury said the bottom line is as the mining investment boom ended, Australia has struggled with weak investment in the non-mining sectors, weighing on the labour market, productivity and ultimately economic growth.

And data from APRA showed that the banks are still doubling down on mortgages, in September. Owner occupied loan portfolios grew 0.48% to $1.03 trillion, after last month’s fall thanks to the CBA loan re-classifications. Investment lending grew just a little to $550 billion, and comprise 34.8% of all loans. Overall the loan books grew by 0.3% in the month. We saw some significant variations in portfolio flows, with CBA, Suncorp, Macquarie and Members Equity bank all reducing their investment loan balances, either from reclassification or refinanced away. The majors focussed on owner occupied lending – which explains all the attractor rates for new business. Westpac continues to drive investor loans hard. Comparing the RBA and APRA figures, it does appear the non-banks are lifting their share of business, as the banks are forced to lift their lending standards. But they are still fighting hard to gain market share, which is not surprising seeing it is the only game in town!

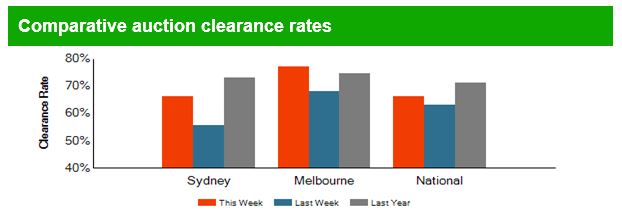

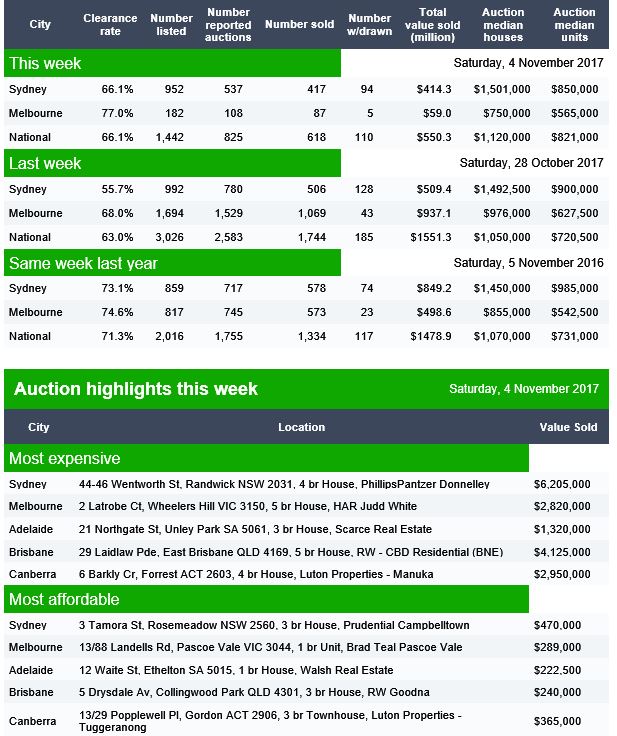

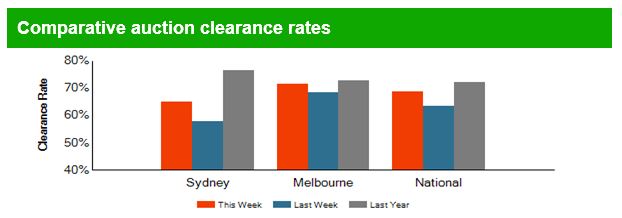

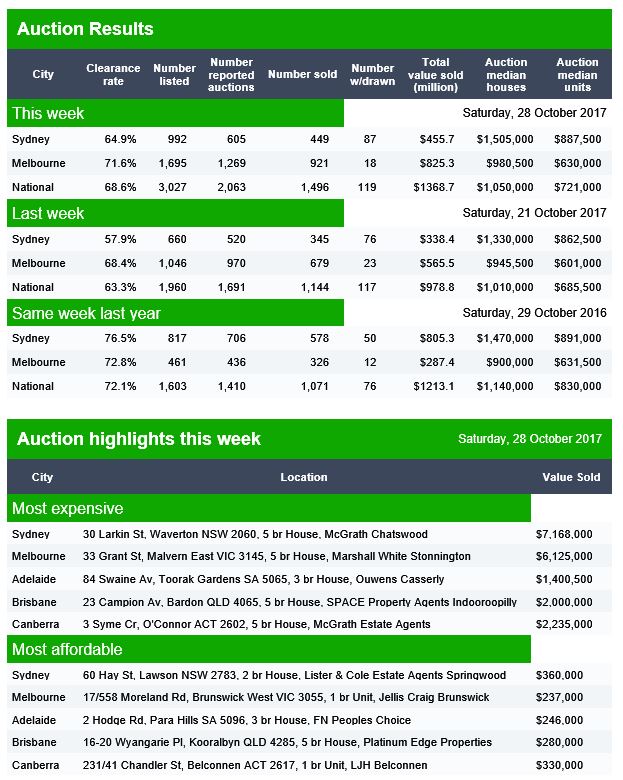

Corelogic’s October property price trends showed that Sydney’s deflating house prices have dragged the property market down across the entire country, the most conclusive sign yet that the boom is over. October is traditionally a bumper month for property sales but average house prices across Australia’s capital cities posted no growth at all. Sydney house prices fell by 0.5 per cent, bringing quarterly losses to 0.6 per cent. Prices in Canberra and Darwin also fell (by 0.1 per cent and 1.6 per cent respectively), while Adelaide and Perth each posted zero growth. Of the capital cities, only Melbourne, Brisbane and Hobart saw property prices increase, at 0.5 per cent, 0.2 per cent and 0.9 per cent respectively. The Australian Property boom is “Officially Over”, despite stronger auction clearance results this past week, which underscored the gap between the momentum in Sydney and Melbourne. Total listings and clearance rates were significantly higher down south.

The HIA reported a further decline in New Home Sales. The results are contained in the latest edition of the HIA New Home Sales Report. During September 2017, new detached house sales fell by 4.5 with a reduction of 16.7 per cent on the multi-unit side of the market.

Lender Mortgage Insurer, Genworth a bellwether for the broader mortgage industry, reported their Q3 performance. While the volume of new business written was down 9.8% on 3Q16, the gross written premium was only down 3.9%. Underlying NPAT was down 14.5% to $40.5 million. The total portfolio of delinquencies rose 4.4% to 7,146, and the loss rate overall was 3 basis points. The regional variations are stark, the performance in Queensland and Western Australia remains challenging and delinquencies are elevated they said. WA was 0.88%, up 19 basis points and QLD was 0.72% up 5 basis points. According to the Australian Financial Security Authority, insolvencies are also rising in WA and QLD, which is mirroring the rise in mortgage delinquency.

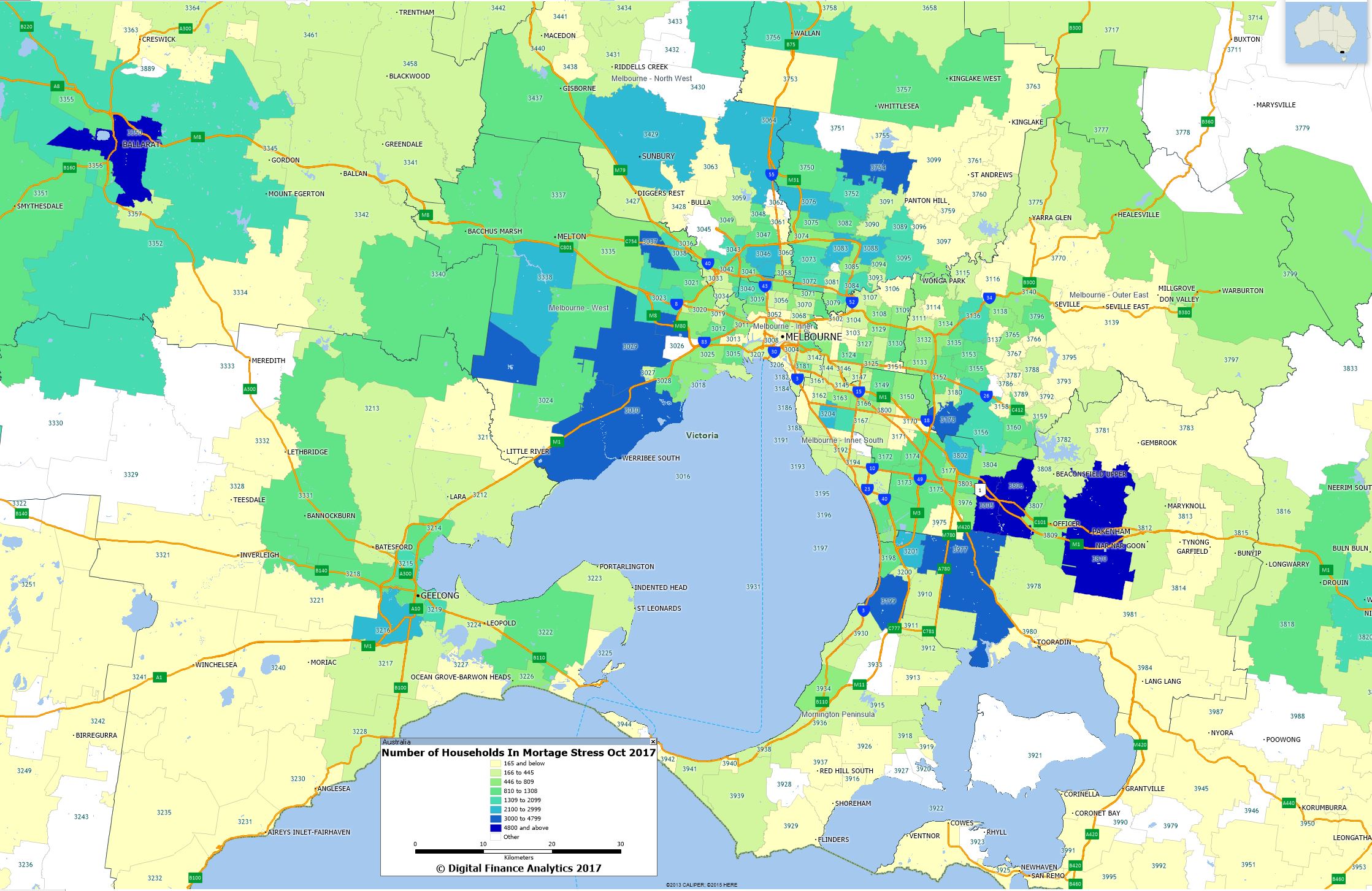

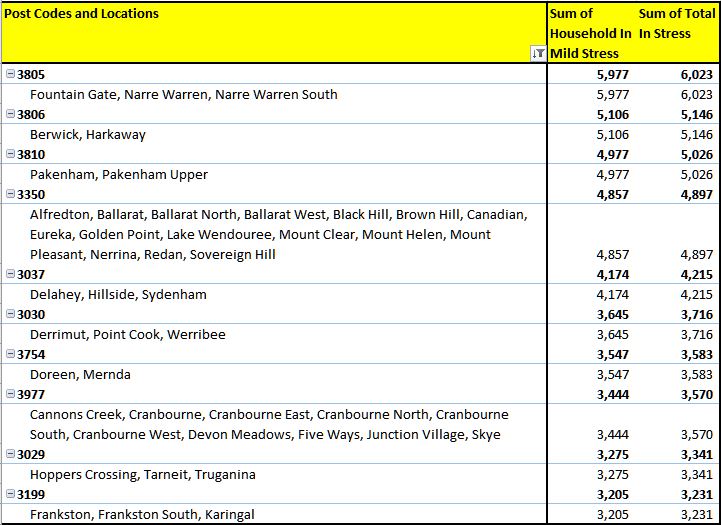

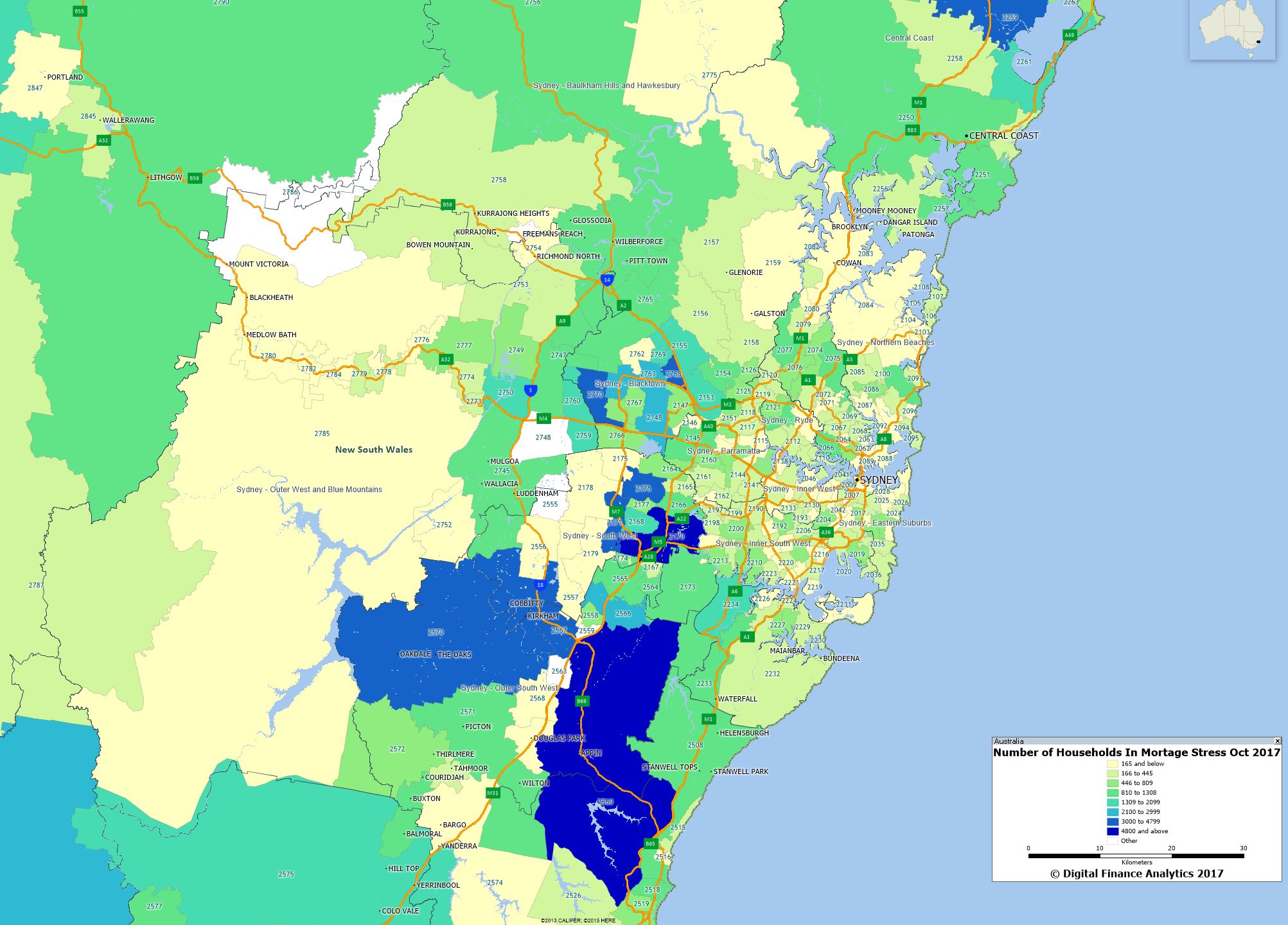

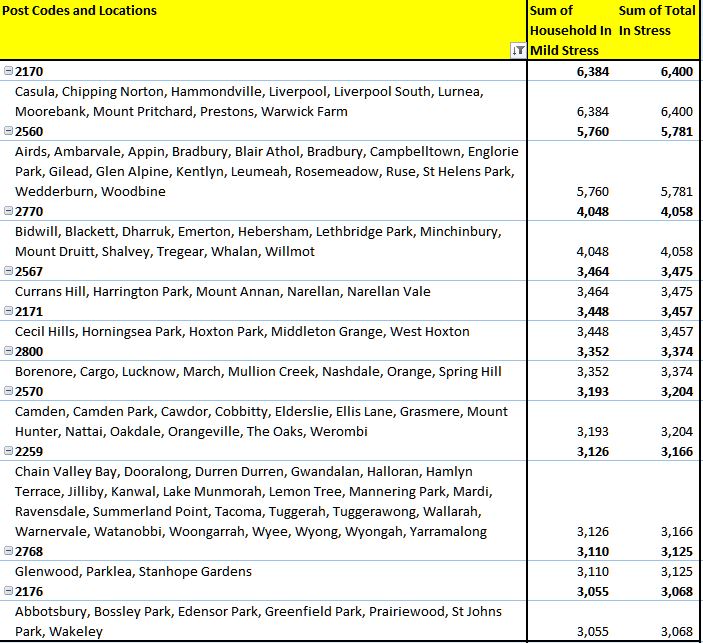

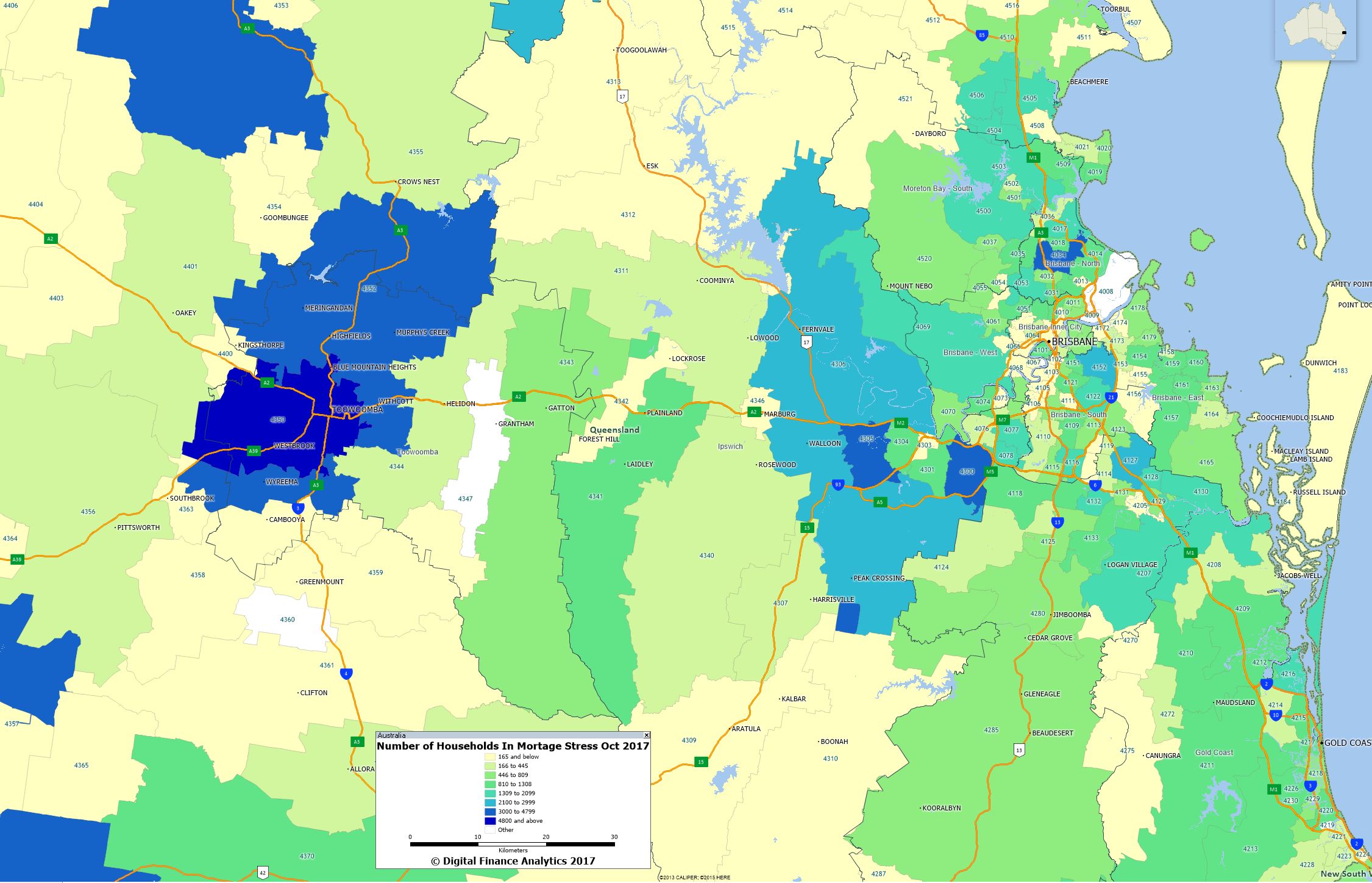

We released our October 2017 Mortgage Stress and Default Analysis. Across Australia, more than 910,000 households are estimated to be now in mortgage stress up 5,000 from last month. This equates to 29.2% of households. More than 21,000 of these are in severe stress, up by 3,000. We see continued default pressure building in Western Australia, as well as among more affluent household, beyond the traditional mortgage belts across the country. We estimate that more than 52,000 households risk 30-day default in the next 12 months, up 3,000 from last month. We expect bank portfolio losses to be around 2.8 basis points ahead, though with WA losses rising to 4.9 basis points.

Risks in the system continue to rise, and while recent strengthening of lending standards will help protect new borrowers, there are many households currently holding loans which would not now be approved. As continued pressure from low wage growth and rising costs bites, those with larger mortgages are having more difficulty balancing the family budget. These stressed households are less likely to spend at the shops, which will act as a further drag anchor on future growth, one reason why retail spending is muted.

The post code with the highest count of stressed households, and up from fourth place last month is NSW post code 2170, the area around Liverpool, Warwick Farm and Chipping Norton, which is around 27 kilometers west of Sydney. There are 6,380 households in mortgage stress here. The average home price is $803,000 compared with $385,000 in 2010. There are around 27,000 families in the area, with an average age of 34. The average income is $5,950. 36% have a mortgage and the average repayment is about $2,000 each month.

Mortgage stress is still strongly associated with fast growing suburbs, where households have bought property relatively recently, often on the urban fringe. The ranges of incomes and property prices vary, but strikingly it is not necessarily those on the lowest incomes who are most stretched. The leverage effect of larger mortgages has a significant impact.

The latest Household Debt Trends from the ABS also showed first, more households are in debt today, compared with 2005-6, and second more households have debts at more than three times their income. Those on lower incomes have borrowed harder, with 50% in the bottom income range borrowing, compared with 44.6% in 2003-4.

Many banks are cutting their mortgage rates to try to attract new borrowers, desperate to write business in a slowing market, because mortgage lending remains the only growth engine in town. We saw announcements from ANZ, and Virgin Money, the Bank of Queensland-owned lender who cut rates by up to 21 basis points and also lifted the maximum LVR to 80%. On the other hand, mirroring other lenders, Westpac is the latest to bring in a number of responsible lending changes affecting how brokers enter in requirements and objectives (R&O) questions for clients. In a note to brokers the bank said: “This will ensure that the correct R&O are captured accurately for all applications submitted and resubmitted and there is a central location that incorporates all the R&O information that has been discussed between yourself and the client with documented evidence of any loan changes,”.

More evidence of the impact of regulation on the mortgage sector came when Bengido and Adelaide Bank’s CEO provided a brief trading update as part of the FY17 AGM. There are some interesting comments on the FY18 outlook. First they have been forced to “slam on the breaks” on mortgage lending to ensure they comply with APRA’s limits on interest only loans and investor loans. As a result, their balance sheet will not grow as fast as previously expected. On the other hand, this should help them maintain their net interest margins, their previous results had shown a steady improvement and strong exit margin. They are forecasting 2.34%.

NAB reported their FY17 results and cash earnings were up 2.5% to $6,642 million, which was below expectations. NAB now has its main footprint in Australia, (and New Zealand). Of the $565 billion in loans, 84% of gross loans are in Australia, and 13% in New Zealand. 58% of the business is mortgages, and 10.9% of gross loans, or $62bn are commercial real estate loans, mainly in Australia. So you can see how reliant NAB is on the property sector. NIM improved a bit, although the long term trend is down. Wealth performance was soft, and expenses were higher than expected, but lending, both mortgages and to businesses, supported the results. They made a provision for potential risks in the retail and the mortgage portfolio, with a BDD charge of 15 basis points but new at risk assets were down significantly this last half. The key risk, or opportunity, depending on your point of view, is the property sector. Currently portfolio losses are low at 2 basis points but WA past 90-day mortgages were up. If property prices start to fall away seriously, new mortgage flows taper down, or households get into more difficulty (especially if rates rise), NAB will find it hard to sustain its current levels of business performance. Ahead, they flagged considerable investment in driving digital, and major cost savings later into FY20 with a net reduction of 4,000 staff.

It is worth saying that back in the year 2000, NAB’s net interest margin was 2.88% compared with 1.85% today, which is lower than ANZ’s 1.99% recently reported. This should be compared with US banks who are achieving 3.21% on average according to Moody’s. It shows that considerable reform of banks in Australia are required. The biggest expense by far is the people they employ. The future of banking is digital! As the mortgage lending tide recedes, the underlying business models of Australian banks are firmly exposed. They have to find a different economic model for their business. Just pulling back to Australia and New Zealand and flogging more mortgages will not solve their problem.

And that’s the Property Imperative Weekly to the 4th November 2017. If you found this useful, as always, do leave a comment below, subscribe to receive future updates, and check back next week for our latest weekly digest

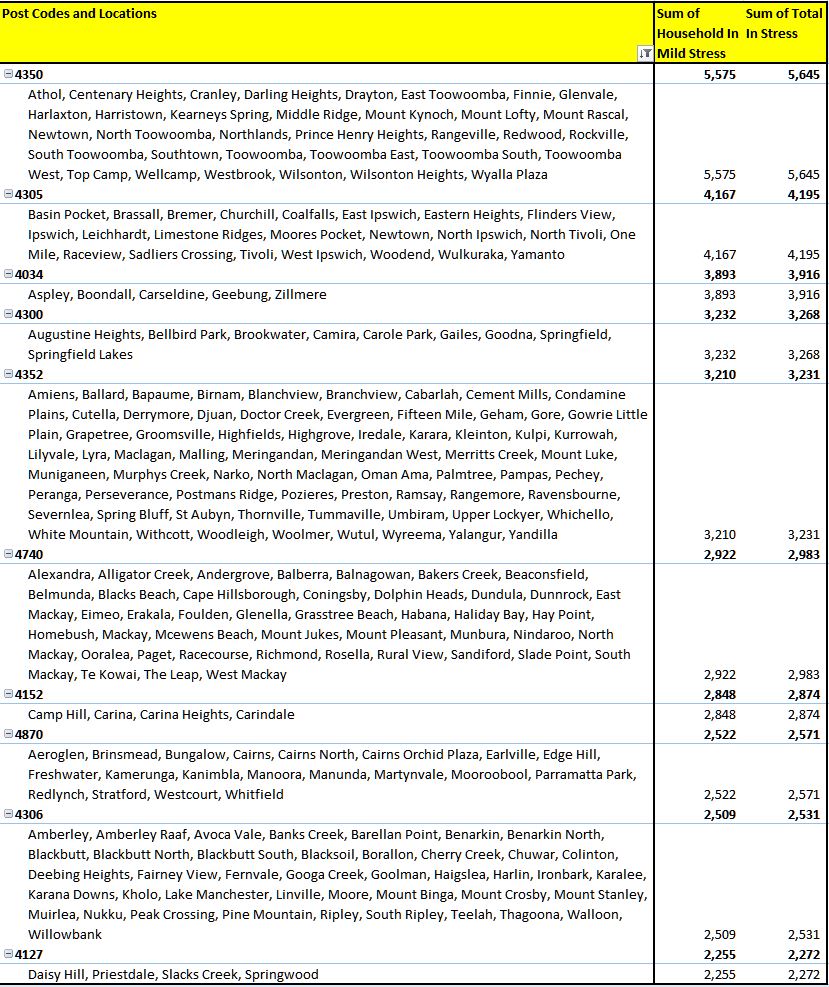

Here is a list of the top 10 most stressed post codes in Queensland, by the number of households in stress.

Here is a list of the top 10 most stressed post codes in Queensland, by the number of households in stress. We will post similar maps and lists across the other states shortly.

We will post similar maps and lists across the other states shortly.