The NZ Reserve Bank has released its consultation paper on possible DTI restrictions. The 36+ page report is worth reading as it sets out the risks ensuring from high risk lending, leveraging experience from countries such as Ireland.

Interestingly they build a cost benefit analysis, trading off a reduction in the costs of a housing and financial crisis with a reduction in the near-term level of economic activity as a result of the DTI initiative and the cost to some potential homebuyers of having to delay their house purchase.

Interestingly they build a cost benefit analysis, trading off a reduction in the costs of a housing and financial crisis with a reduction in the near-term level of economic activity as a result of the DTI initiative and the cost to some potential homebuyers of having to delay their house purchase.

Submissions on this Consultation Paper are due by 18 August 2017.

In 2013, the Reserve Bank introduced macroprudential policy measures in the form of loan to-value ratio (LVR) restrictions to mitigate the risks to financial system stability posed by a growing proportion of residential mortgage loans with high LVRs (i.e. low deposit or low equity loans). This increase in borrower leverage had gone hand-in-hand with significant increases in house prices, particularly in Auckland. The Reserve Bank’s concern was the possibility of a sharp fall in house prices, in adverse economic circumstances where some borrowers had trouble servicing loans. Such an event had the potential to undermine bank asset quality given the limited equity held by some borrowers.

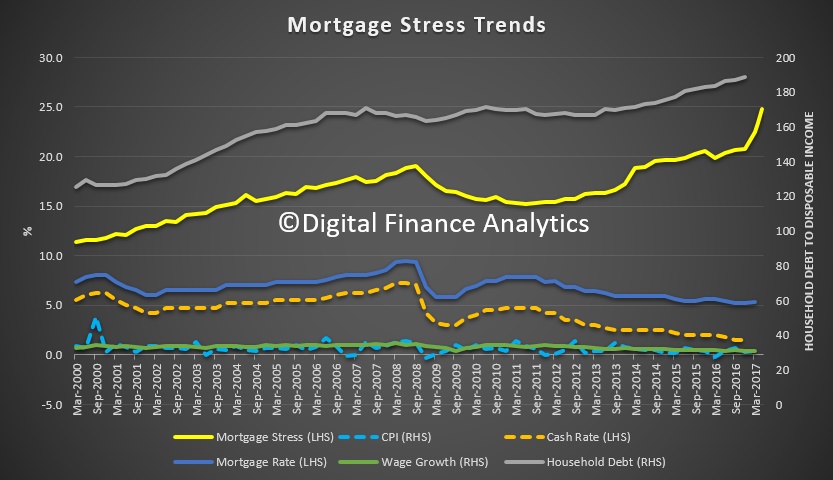

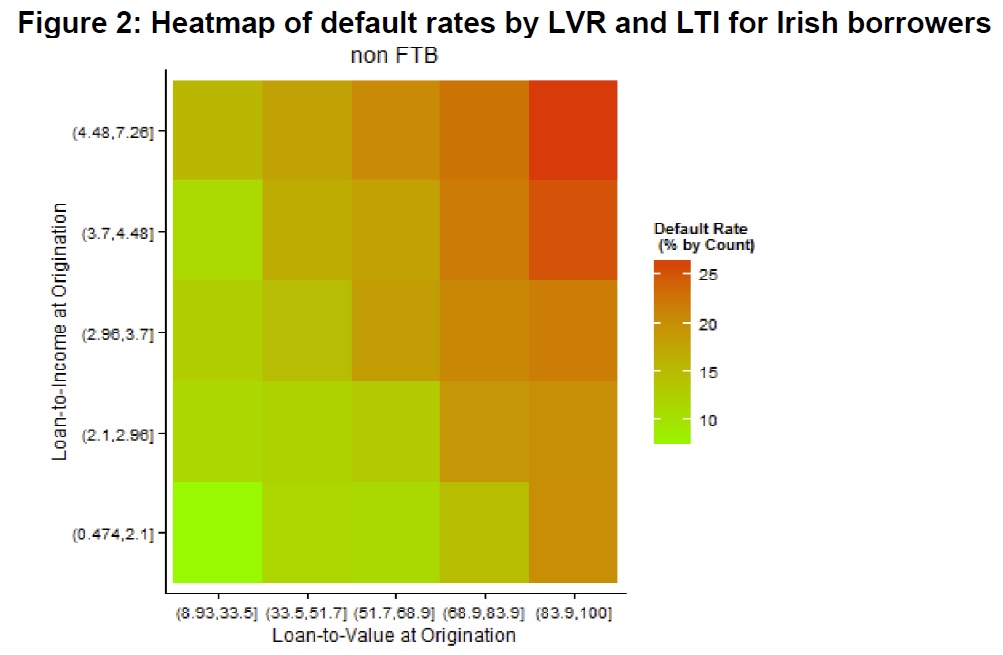

The Reserve Bank believes LVR restrictions have been effective in reducing the risk to financial system stability that can arise due to a build-up of highly-leveraged housing loans on bank balance sheets. However, LVRs relate mainly to one dimension of housing loan risk. The other key component of risk relates to the borrower’s capacity to service a loan, one measure of which is the debt-to-income ratio (DTI). All else equal, high DTI ratios increase the probability of loan defaults in the event of a sharp rise in interest rates or a negative shock to borrowers’ incomes. As a rule, borrowers with high DTIs will have less ability to deal with these events than those who borrow at more moderate DTIs. Even if they avoid default, their actions (e.g. selling properties because they are having difficulty servicing their mortgage) can increase the risk and potential severity of a housing related economic crisis.

While the full macroprudential framework will be reviewed in 2018, the Reserve Bank has elected to consult the public prior to the review. This consultation concerns the potential value of a policy instrument that could be used to limit the extent to which banks are able to provide loans to borrowers that are a high multiple of the borrower’s income (a DTI limit). A number of other countries have introduced DTI limits in recent years, often in association with LVR restrictions. In 2013, the Bank and the Minister of Finance agreed that direct, cyclical controls of this sort would not be imposed without the tool being listed in the Memorandum of Understanding on Macroprudential Policy (the MoU). Hence, cyclical DTI limits will only be possible in the future if an amended MoU is agreed.

The purpose of this consultation is for the Reserve Bank, Treasury and the Minister of Finance to gather feedback from the public on the prospect of including DTI limits in the Reserve Bank’s macroprudential toolkit.

Throughout the remainder of the document we have listed a number of questions, but feedback can cover other relevant issues. Information provided will be used by the Reserve Bank and Treasury in discussing the potential amendment of the MoU with the Minister of Finance. We present evidence that a DTI limit would reduce credit growth during the upswing and reduce the risk of a significant rise in mortgage defaults during a subsequent severe economic downturn. A DTI limit could also reduce the severity of the decline in house prices and economic growth in that severe downturn (since fewer households would be forced to sharply constrain their consumption or sell their house, even if they avoided actual default). The strongest evidence that these channels could materially worsen an economic downturn tends to come from countries that have experienced a housing crisis in recent history (including the UK and Ireland). The Reserve Bank believes that the use of DTI limits in appropriate circumstances would contribute to financial system resilience in several ways:

– By reducing household financial distress in adverse economic circumstances, including those involving a sharp fall in house prices;

– by reducing the magnitude of the economic downturn, which would otherwise serve to weaken bank loan portfolios (including in sectors broader than just housing); and

– by helping to constrain the credit-asset price cycle in a manner that most other macroprudential tools would not, thereby assisting in alleviating the build-up in risk accompanying such cycles.The policy would not eliminate the need for lenders and borrowers to undertake their own due diligence in determining that the scale and terms of a mortgage are suitable for a particular borrower. The focus would be systemic: on reducing the risk of the overall mortgage and housing markets becoming dysfunctional in a severe downturn, rather than attempting to protect individual borrowers. The consultation paper notes that DTIs on loans to New Zealand borrowers have risen sharply over the past 30 or so years, with further increases evident since 2014. This partly

reflects the downward trend in interest rates over the period. However, interest rates may rise in the future. While the Reserve Bank is continuing to work with banks to improve this data, the available data also show that average DTIs in New Zealand are quite high on an international basis, as are New Zealand house prices relative to incomes.Other policies (such as boosting required capital buffers for banks, or tightening LVR restrictions further) could be used to target the risks created by high-DTI lending. The Bank does not rule out these alternative policies (indeed, we are currently undertaking a broader review of capital requirements in New Zealand) but consider that they would not target our concerns around mortgage lending as directly or effectively. For example, while higher capital buffers would provide banks with more capacity to withstand elevated housing loan defaults, they would do little to mitigate the feedback effects between falling house prices, forced sales and economic stress.

The Reserve Bank has stated that it would not employ a DTI limit today if the tool was already in the MoU (especially given recent evidence of a cooling in the housing market and borrower activity), it believes a DTI instrument could be the best tool to employ if house prices prove resurgent and if the resurgence is accompanied by further substantial volumes of high DTI lending by the banking system. The Reserve Bank considers that the current global environment, with low interest rates expected in many countries over the next few years, tends to exacerbate the risk of asset price cycles arising from ‘search for yield’ behaviour, making the potential value of a DTI tool greater.

The exact nature of any limit applied would depend on the circumstances and further policy development. However, the Reserve Bank’s current thinking is that the policy would take a similar form to LVR restrictions. This would involve the use of a “speed limit”, under which banks would still be permitted to undertake a proportion of loans at DTIs above the chosen threshold. By adopting a speed limit approach, rather than imposing strict limits on DTI ratios, there would be less risk of moral hazard issues arising from a particular ratio being seen as “officially safe”. Exemptions similar to those available within the LVR restriction policy would also be likely to apply.