Are First Time Buyers really under the affordability gun? What will the impact of the surprising slowdown in residential construction be? And how will the bank levy play out in the light of this week’s ratings downgrades? Find out as you watch the latest edition of the Property Imperative weekly.

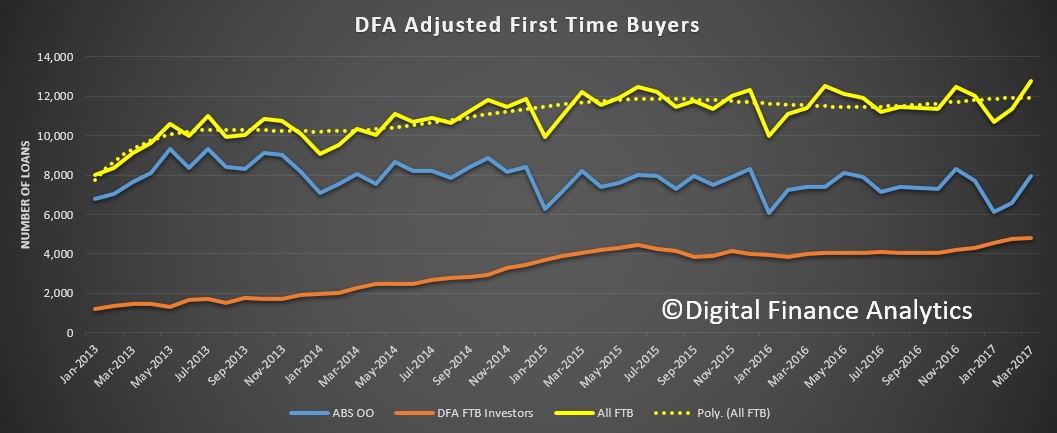

First, are first time buyers are really finding it more difficult to enter the property market at the moment? The most recent statistics showed there was a bounce in the number of buyers, and this has been attributed to low interest rates, stagnating property price growth and enhanced first home buyer incentives. This despite property investors beating other purchasers to the punch.

Genworth, the Lender Mortgage Insurer, changed their underwriting guidelines to include the First Home Owner Grant as an acceptable source if other true ‘genuine savings’ cannot be found. Genworth’s new conditions also places responsibility on the lender to ensure the borrower is eligible to receive a FHOG at the time of the application.

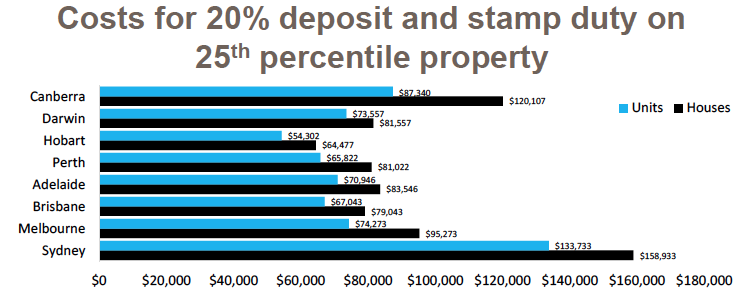

Demographer Bernard Salt’s jocular observation of young adults wasting money on smashed avocado has been put into perspective. Even if young Australian do give up extravagant brunches and put the funds towards saving for a house, it will take years, or even decades, to accumulate enough cash for the deposit and stamp duty on a home. A 20% deposit and stamp duty required to buy a house in Sydney is $159,000, based on new data from CoreLogic. That’s equivalent to 20 years’ worth of smashed avo.

But then again, do first time buyers really need a 20% deposit? Back in 2015, the Reserve Bank noted: “the deposit required of a first home buyer is more often in the 5–10 per cent range.” Whilst regulators have tightened the screws since then, there are still mortgages with below 20 per cent deposits to be found, according to data from RMIT’s Centre for Urban Research. Many of these rely on access to Lenders Mortgage Insurance, which of course protects the bank, not the borrower directly.

A report from Standard and Poor’s highlighted the risks in the Australian mortgage sector, and said that LMI’s might get squeezed by tightening lending restrictions and elevated claims, especially from loans in Western Australia and Queensland.

Our survey data on First Time Buyers indicates that there is incredibly strong demand for property, from both new migrants and existing residents. But that they are finding it harder to get funding, despite some grants being available, thanks to low returns on deposits, and low or no wage growth which is making it harder to save in the first place. We do see some lenders loosening their lending criteria for first time buyers with a saving history, but they are looking harder at household expenses, so overall funding is still harder to come by than a year ago. Our data shows this clearly, and our latest core market data is available now for paying clients.

So back to the Standard and Poor’s assessment of the housing sector, and their rating of the banks. Some were surprised when the ratings agency came out with an assessment before the latest round of house price data is out, but their latest assessment is finely balanced, on one hand calling out the elevated risks emanating from rising household debt and risks of a property correction, whilst on the other suggesting that recent regulatory intervention should help to manage the adjustment.

So back to the Standard and Poor’s assessment of the housing sector, and their rating of the banks. Some were surprised when the ratings agency came out with an assessment before the latest round of house price data is out, but their latest assessment is finely balanced, on one hand calling out the elevated risks emanating from rising household debt and risks of a property correction, whilst on the other suggesting that recent regulatory intervention should help to manage the adjustment.

But overall, risks are higher and their revised credit profiles reflect this with more than 20 entities downgraded. Whilst the majors rating has not changed – reflecting the implicit government guarantee that their “too-big-to-fail” status gives them, and Suncorp remains at its current rating, despite a tough quarter; both Bendgio Bank and Bank of Queensland took a downgrade.

The consequence for these regionals is that funding costs just went up (and probably by more than a 6 basis point tax on the majors would have given in relative benefit). They have high customer deposits, but again the regional bank playing field is tilting against them when it comes to long term funding. This put the bank tax into a different light, as the Government argued the tax would help level the playing field.

In addition, the big banks came out with an estimate of the impact of the proposed tax. The budget papers estimated it would yield more than $6 billion over 4 years, based on a 6 basis charge on selected liabilities. The banks say on an annual pre-tax basis they would pay around $1.38 billion annually, but only $965m post tax (as the tax would be an allowable expense). The Government confirmed the tax would be tax deductable.

So, the tax won’t deliver the planned revenue, and the 6 basis points benefit the regional banks might have been expected to see relative to the majors has been more than offset by the credit downgrades. This has led to calls to lift the tax to deliver the full planned value, and also extend it to large foreign banks operating here.

But there is a broader point to consider. The majors are protected by the implicit guarantee that if they got into financial difficulty, the Government would bail them out. S&P explained this is why they were not downgraded, but went on to say if Australia’s country rating fell, they would be. It seems clear that as the levy is making the implicit guarantee more explicit, (such that Macquarie who is caught by the levy, got a ratings upgrade, whilst others like Bendigo and Adelaide Bank did not); the reach of this implicit guarantee is in question. To put it sharply, would the Government really let Bendigo fall over; we think not. So the whole question of who has and who does not have this protection is in the air. This all has a direct impact on funding costs, and product pricing. So how this plays out will directly impact the interest rates paid by mortgage holders and to savers. We think the need for a proper inquiry into the bank tax just got stronger. It’s worth remembering the UK’s approach to a bank tax took three goes to get right!

What seems to have been a late play for more revenue from the Government has descended into the complexity of bank funding and risk.

Finally, ten years on from the 2007 Global Financial Crisis, there were a number of good summaries of what we have learnt. One of the best was from the St. Louis Federal Reserve. They said the root causes of the crisis could be traced to excessive mortgage debt, sharply higher mortgage rates, an overheated housing market and a lack of broad oversight/insight.

Stepping forward to the current situation in Australia, it seems to me these factors are alive and well here. Household debt has never been higher, mortgage rates are set to rise further whilst incomes are squeezed, home prices are too high on any measure, and the regulators only recently started to react to the true impact of debt exposed households. This, in the week the latest personal insolvency data showed a significant rise, not just in WA, but across the nation and residential construction slowed last quarter, suggesting the number of new starts will continue to fall.

There was an excellent research piece from institutional investment fund JCP Investment Partners, picked up in the AFR. Their granular analysis of the mortgage sector (including leveraging our data), underscores the risks in the mortgage books, and explains the RBA’s recent change of tune on household finances. Critically, they showed that many households have very high loan to income ratios.

In the light of this, we think S&P called the market right, and it’s now a question of whether we will get an orderly adjustment or not. The jury is out, but the latest home price data is also suggesting a fall, despite ongoing high auction clearance rates.

In the light of this, we think S&P called the market right, and it’s now a question of whether we will get an orderly adjustment or not. The jury is out, but the latest home price data is also suggesting a fall, despite ongoing high auction clearance rates.

At best, we remain on a knife edge. Check back next week for our latest update.

Melbourne’s southern and western suburbs and CBD will be worst affected. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au

Melbourne’s southern and western suburbs and CBD will be worst affected. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au The prediction for the Gold Coast is dire. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au

The prediction for the Gold Coast is dire. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au Newcastle and the NSW Central Coast will be inundated. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au

Newcastle and the NSW Central Coast will be inundated. Photo: Coastalrisk.com.au