Chris Radford and Michelle Apostolopoulos are high school sweethearts. They met and fell in love at Northcote public school, which sits on the same main road that runs near both their parents’ fully paid off houses.

They both rent in Melbourne and are fast approaching the age their parents married, bought houses and started families. Repeating that feat in today’s market seems impossible.

Chris, 24, has spent the last six years of his life stacking shelves in a trendy inner-city supermarket, so he knows the price of avocados – that symbol of millennial decadence that is supposedly holding him back from property ownership.

“Four bucks, five bucks each. Yeah, I know how much they cost,” he says. “I don’t eat a lot of avocado to begin with.”

The couple, who plan to marry soon, are exactly who Treasurer Scott Morrison’s latest federal budget was supposed to help: hard-working, hard-saving Australians who want nothing more than a modest home to call their own.

Unlike their parents’ generation, the ‘Australian Dream’ seems to be getting further out of reach, what with rising prices, penalty rate cuts and record-low wage growth.

Chris pays $110 a week for a room in a house he shares with two friends in the Melbourne suburb of Moonee Ponds. When it rains, water drips through the ceiling into a strategically placed pot.

The house will soon be knocked down for apartments, so the landlord has given up on the place.

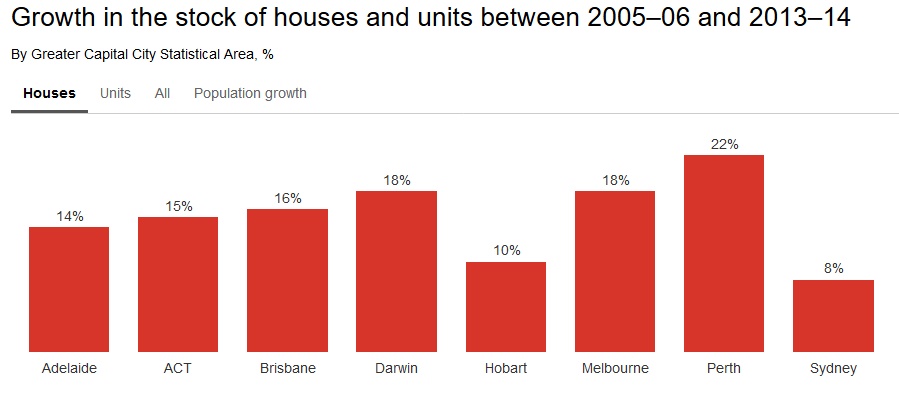

When his parents bought their house in Thornbury for $80,000 back in 1991 it was not much of a stretch for two people in their mid-20s. It is now worth at least $1 million, probably more.

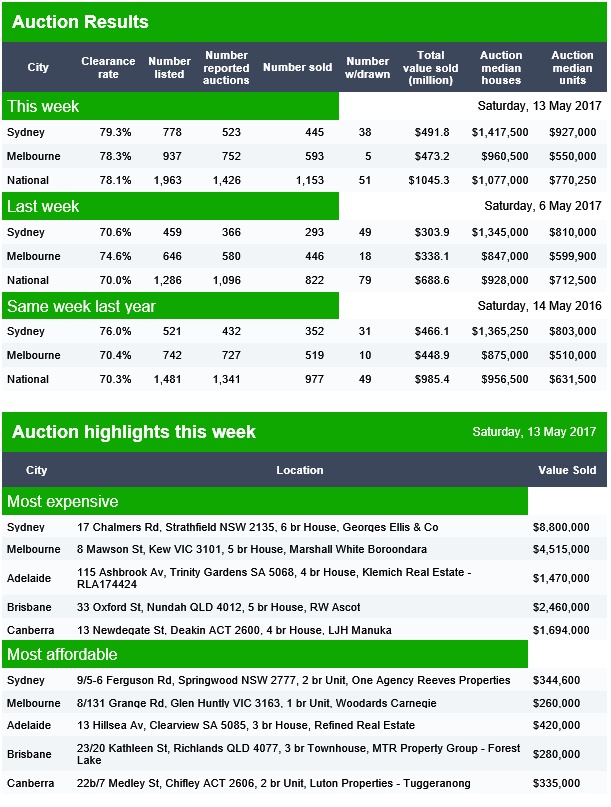

Because of this enormous increase in value, buying even a more modest house today requires vastly more effort. Chris and Michelle, 23, estimate that a median-priced Melbourne home will require them to save a 20 per cent deposit of $150,000.

Even if they were to save every dollar they earn, it would still take them years to build that much – and that’s without taking price growth into account.

“It’s so unfair, two people should be able to save enough in a few years for a house!” Michelle says.

“Even if we saved hard I know we wouldn’t be able to afford within 32 kilometres of here.”

Part of the reason that saving is so hard for the couple is the new round of attacks on their pay.

Chris has worked his supermarket job all through high school and now into university. He works Sundays and has for years. He also works unpaid at an internship as part of his university degree, which requires him to work full-time on top of his part-time work.

This leaves him relying heavily on weekend penalty rates — which he’ll lose come July 1 because of a recent decision by the Fair Work Commission.

“If I didn’t have to work on Sunday, I wouldn’t,” he says.

Michelle, too, regularly works weekends. But because she works for one of Australia’s two main supermarkets, she’ll be lucky enough to keep her penalty rates.

“People who work weekends miss out on seeing family and friends,” she says.

“You deserve [penalty rates], you’ve busted your arse all weekend.”

They’re both disappointed the government didn’t do more in the budget to make things easier for low-paid workers and aspiring property buyers like themselves. Treasurer Morrison’s plan to allow first home buyers to tip up to $30,000 into their superannuation doesn’t excite them.

“When you really look at the details it starts looking practically impossible,” Michelle says.

“The government isn’t doing anything to make it easier to buy a house.”

To make matters even worse, with the university debt repayment threshold dropping, Chris and Michelle will both have to pay back more to the government each year.

“A lot of people think you’re not working hard enough if you can’t save a deposit. They just pick on young people because we can’t do anything about it,” she says.

“What are you supposed to do? Store everything in a cardboard box, then live in the cardboard box too?”