Changes to stamp duty for first time owner occupiers and a vacant property tax have been confirmed by the Victorian Government today. Separately an equity share scheme was announced to assist first time buyers.

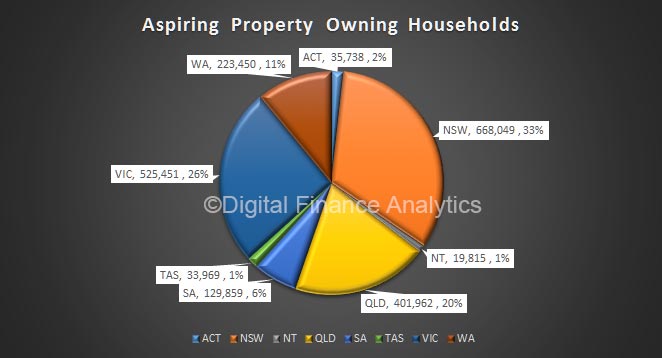

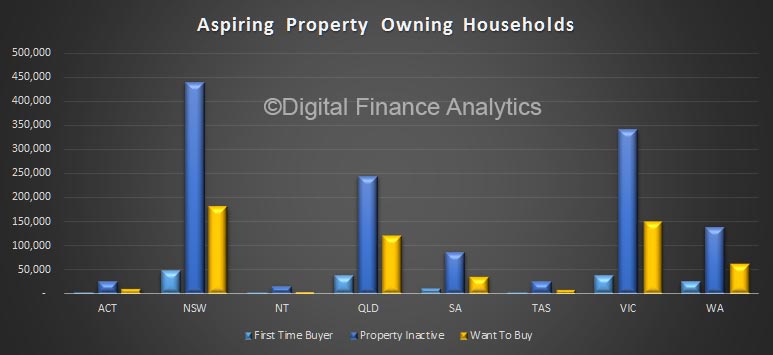

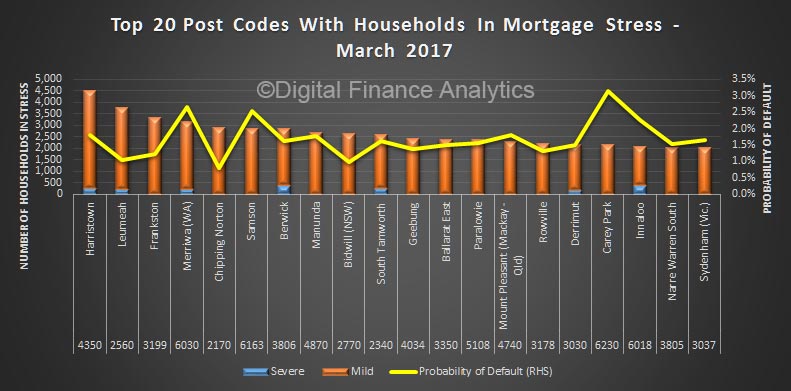

As a package of measures they will certainly impact the market, and whilst the tax breaks and first owner grants may simply lift prices, the tax on vacant properties and equity share strategies could certainly re-balance the market towards owner occupied purchasers. Our research shows there are more than 500,000 households in Victoria are currently struggling to enter the market.

Stamp duty will be abolished for first home buyers for purchases below $600,000, helping thousands of Victorians find their first home, as the Andrews Labor Government tackles housing affordability head on.

Those buying a home valued between $600,000 and $750,000 will also be eligible for a concession, applied on a sliding scale. The exemption and concession will apply to both new and established homes, in a move that is expected to help 25,000 Victorians find their first home.

In a further move to help tilt the scales back towards home owners, the Government will also remove off-the-plan stamp duty concessions on investment properties.

The off-the-plan stamp duty concession will now be available solely for those who intend to live in the property or who are eligible for the first home buyer stamp duty concession.

At the same time, a Vacant Residential Property Tax will address the number of properties being left empty across inner and middle suburbs of Melbourne.

Under the changes, owners who unreasonably leave these properties vacant will instead be encouraged to make them available for either purchase or rent.

The Vacant Residential Property Tax will be levied at 1 per cent, multiplied by the capital improved value of the taxable property. For example, if the property has a capital improved value of $500,000, the amount paid will be $5,000.

There will be a number of exemptions, recognising there are some legitimate reasons for a property being left vacant, including holiday homes, deceased estates and homes owned by Victorians who are temporarily overseas.

Each of these changes are part of the Labor Government’s plan to help more Victorians break into the housing market.

The Equity Share scheme HomesVic was also announced.

Thousands of Victorians, dreaming of buying their first home, will be able to make their dream a reality, thanks to two new changes announced by the Andrews Labor Government.

A new $50 million pilot scheme, HomesVic, will target first home buyers who are able to meet regular mortgage repayments, but because of rising rental costs, haven’t been able to save a big enough deposit.

Under the scheme, to be introduced in January 2018, HomesVic will co-purchase up to 400 homes, taking an equity share of up to 25 per cent in these properties. It will be available for both new and existing homes.

By allowing homebuyers to purchase less than 100 per cent of the property, they will require a smaller deposit and are able to enter the market sooner. In the long term, it will also mean having a smaller loan to service.

Eligible applicants will include couples earning up to $95,000, and singles earning up to $75,000. Buyers will need to have a 5 per cent deposit. The pilot will be tested across the state, and when the properties are sold, HomesVic will recover its share of the equity.

To further improve buyers’ chances of owning their own home, the Labor Government will also contribute $5 million to a national, community sector, shared equity scheme, Buy Assist.

With similar goals to HomesVic, Buy Assist will help deliver an additional 100 shared equity homes and help low to medium income households get a foothold in the property market.

The Government is also set to give first home buyers priority in government-led urban renewal developments, with at least 10 per cent of all properties allocated to first time buyers.

This approach will be used for the first time at the Arden development.

The plan to develop the 56 hectare site Arden, announced by the Labor Government last year, could be home to around 15,000 people. Under this policy 1,500 of those could be first home buyers.

Finally, in a separate release, the overall portfolio of actions were summarised under “Homes for Victorians”

Every Victorian deserves the safety and security of a home.

But for many, that’s becoming increasingly harder.

A significant number of Victorians, particularly young Victorians, are struggling to break into the housing market.

House prices are rising and upfront costs – a deposit, stamp duty and fees – quickly add up.

It’s getting harder for renters too.

Many struggle to meet high rental prices, or instead choose to live in unsuitable housing. Some don’t have the security they need, or the capacity to personalise their home as they would like.

At the same time, the number of Victorians who need to access public and community housing is growing. Waiting lists are long, and many of our existing homes have fallen into disrepair.

In short, too many Victorians don’t have a real choice about where they live, or the type of home they live in.

And as our population grows, inaction will only make things worse.

Fixing this problem isn’t simple.

It’s why Homes for Victorians provides a co-ordinated approach across government, and across our state. It includes:

- abolishing stamp duty for first time buyers on homes up to $600,000 and cuts to stamp duty on homes valued up to $750,000

- doubling the First Home Owner Grant to $20,000 in Regional Victoria to make it easier for people to build and stay in their community

- creating the opportunity for first home buyers to co-purchase their home with the Victorian Government

- making long-term leases a reality

- building and redeveloping more social housing – supporting vulnerable Victorians while creating thousands of extra jobs in the construction industry.

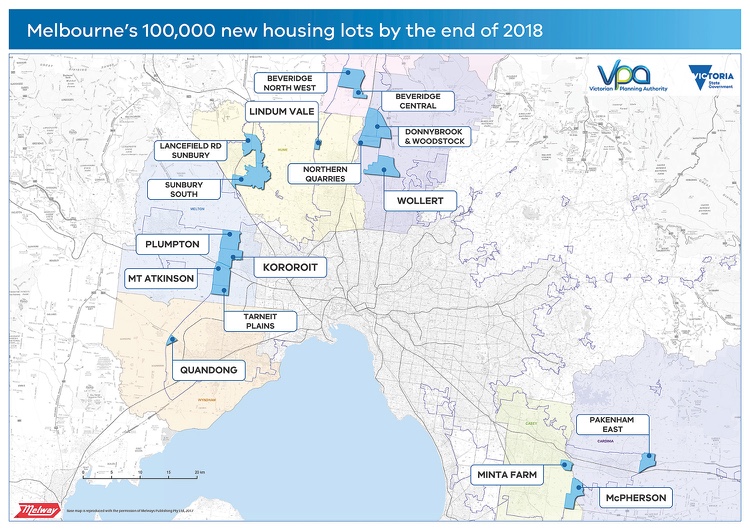

It builds on existing work being done, including the soon to be released Plan Melbourne 2017-2050, reform of the Residential Tenancies Act 1997, the Better Apartment guidelines and the Family Violence Housing Blitz.

It also builds on our efforts to better connect Victorians with services and infrastructure. From schools to health care, roads to public transport, regardless of where they live, every Victorian should have access to the things they need.

It’s a big job, but the aim is simple: to give every Victorian every opportunity to find a home.