The number of Property Investing households in Australia in rising. Today we look specifically at the fastest growing segment – Portfolio Property Investors.

This sector, though highly leveraged, is enjoying strong returns from property investing, are benefiting from generous tax breaks and many are expecting to purchase more property this year. However, we think there are some potential clouds on the horizon, and that the risks linked to this segment are higher than many believe to be true. Our latest Video Blog post discusses the findings from our research.

The investment property sector is hot at the moment, with around 1.5 million borrowing households now holding investment property and the number of investment loans is the rise. In December according to the RBA, investment loans grew at 0.8%, twice as fast as owner occupied loans, and around 36% of all loans are for investment purposes.

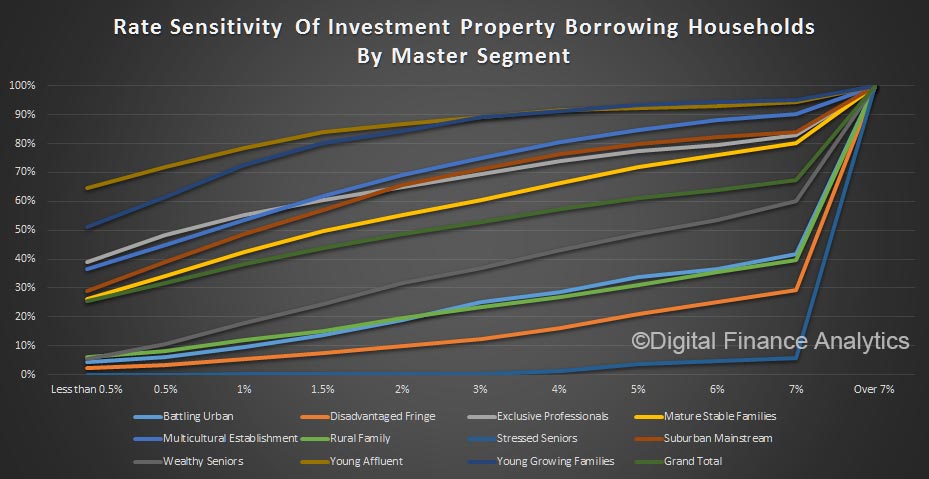

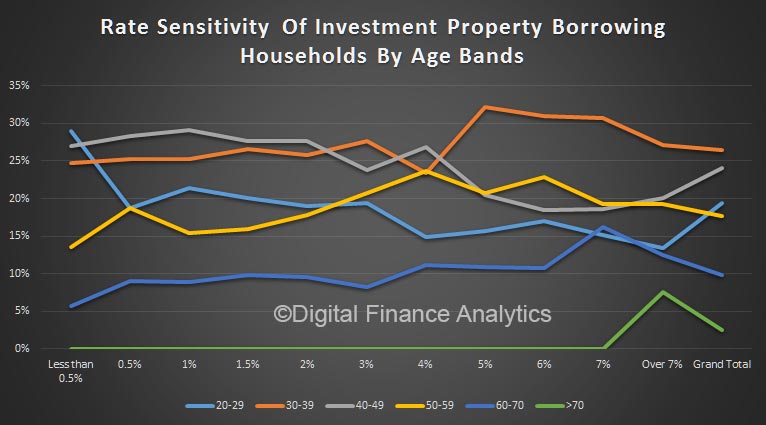

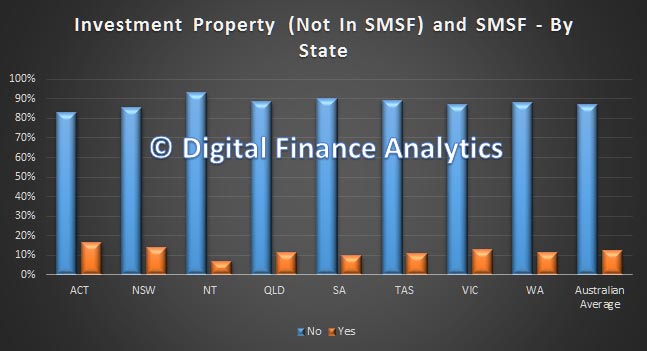

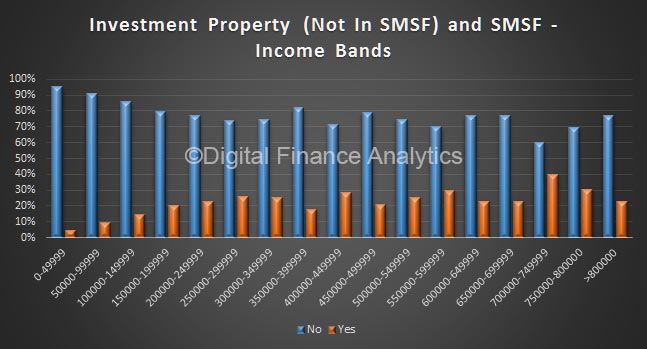

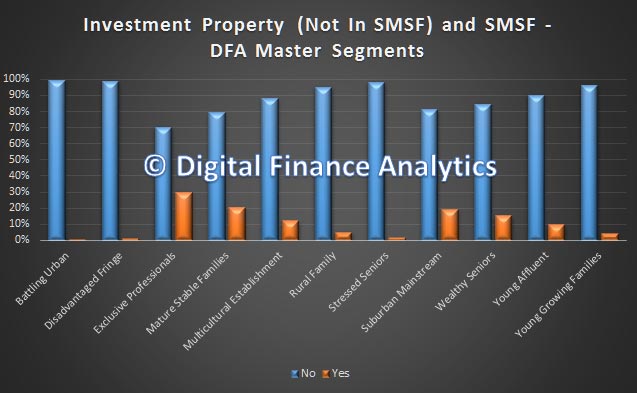

But not all property investors are created equal. Using data from our large scale household surveys, we have looked in detail at those who hold multiple investment properties.

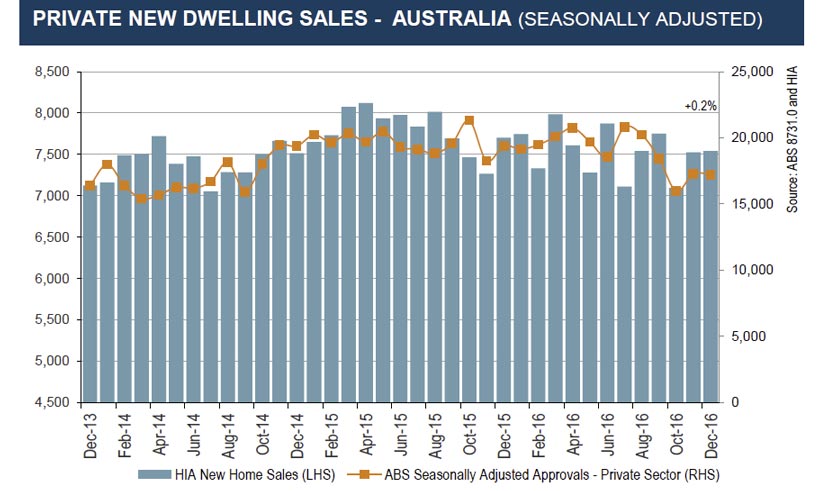

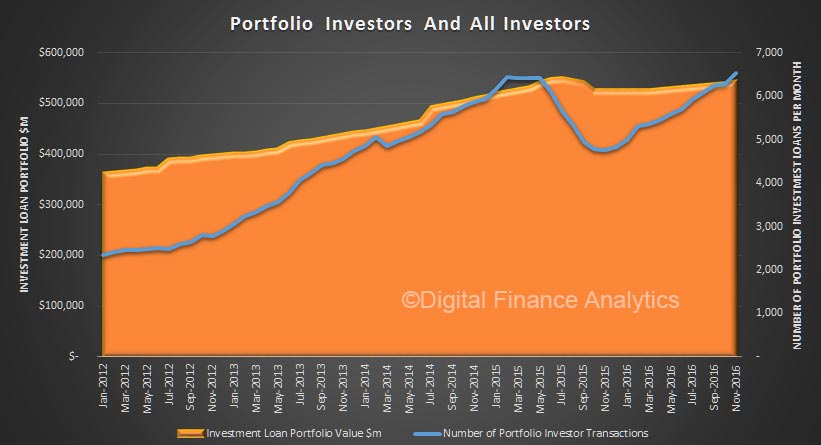

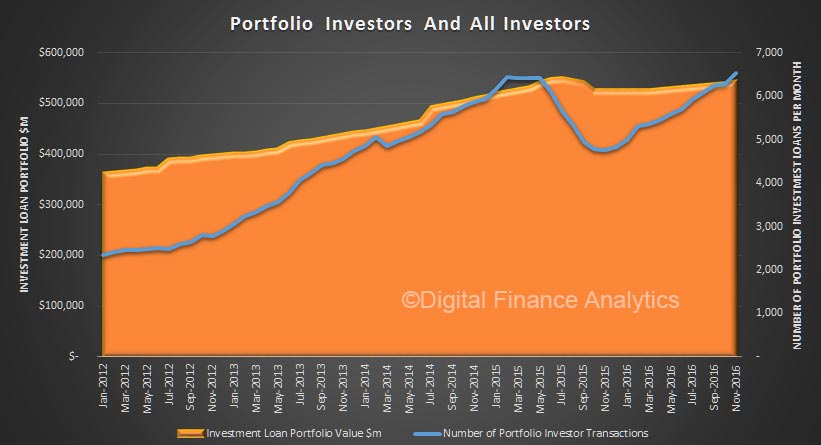

These Portfolio Investors have become a significant force in the market. For example, in November about twenty per cent of transactions were from portfolio investors – or about six thousand transactions. Whilst overall investment loans grew at 0.8%, there was an estimated 4% increase in transactions from Portfolio Investors.

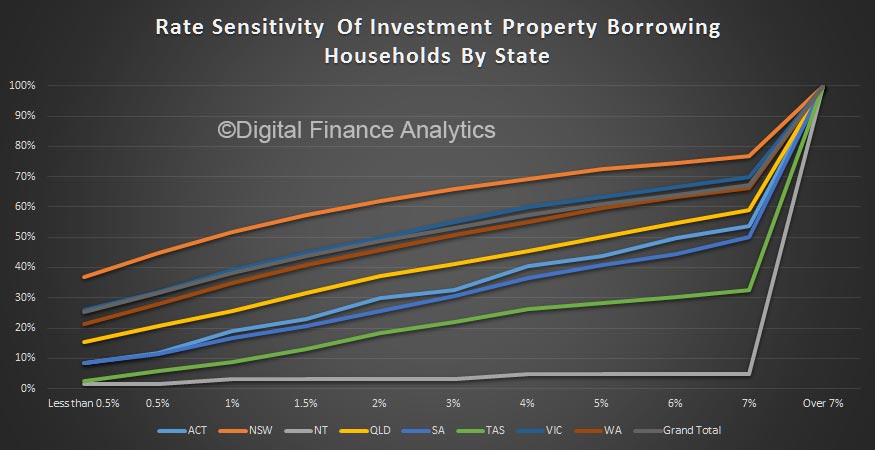

If we plot the overall loan growth trends against the proportion who are Portfolio Investors, we see a that since late 2015, it is these Portfolio Investors who have been driving the market. In addition, more than half of these transactions are in New South Wales, which is the property investor honeypot.

If we plot the overall loan growth trends against the proportion who are Portfolio Investors, we see a that since late 2015, it is these Portfolio Investors who have been driving the market. In addition, more than half of these transactions are in New South Wales, which is the property investor honeypot.

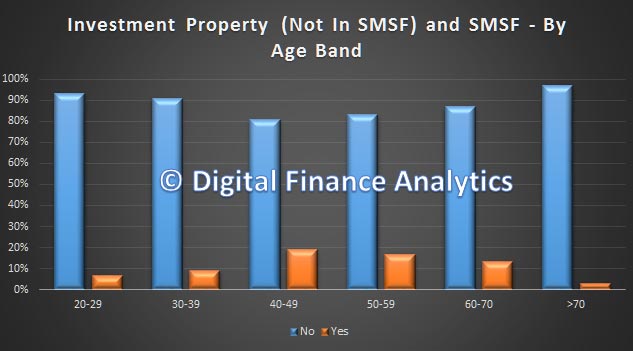

Many Portfolio Investors will have three or four properties, though some have more than twenty and the average is about eight. Some of these households have taken to property investment as a full-time occupation, others see it as their main wealth building strategy.

Property portfolios vary considerably, although we note that there is a tendency to hold a portfolio of lower value property – such as would be suitable for first time buyers, rather than million dollar homes. This is because the rental income is better aligned to the value of the property, and there is more demand from renters, and greater supply.

About half of portfolio investors prefer to buy newly build high-rise apartments, whilst others prefer to purchase a property requiring renovation, because they believe renovation is the key to greater capital appreciation in the long run, even if rental income is foregone near term.

Property Investors are able to get a number of tax breaks, especially if negatively geared. They are able to offset both capital costs by way of adjustments to the capital value on resale and recurring costs, which are offset against income.

Together negative gearing and capital gains makes investment property highly tax effective. There is good information on the ATO site which walks through all the benefits, but in summary you can claim:

In terms of financing, you can also claim:

- stamp duty charged on the mortgage

- loan establishment fees

- title search fees charged by your lender

- costs (including solicitors’ fees) for preparing and filing mortgage documents

- mortgage broker fees

- fees for a valuation required for loan approval

- lender’s mortgage insurance, which is insurance taken out by the lender and billed to you.

Stamp duty and legal expenses can be claimed as capital expenses.

Given the strong capital appreciation we have seen in property values, especially down the east coast, portfolio investors are less concerned about rental incomes than capital values. Indeed, in recently published research we showed that about half of investment property holders were losing money in cash flow terms – but significantly, portfolio investors were on average doing better.

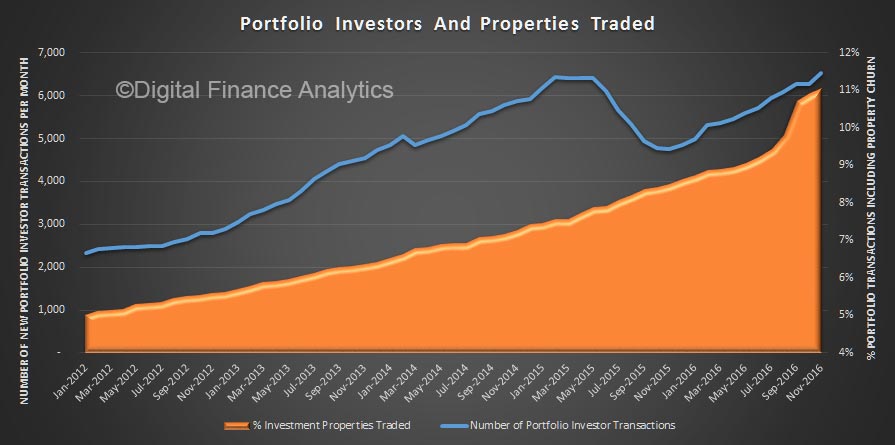

But these capital gains are now being crystallised by sassy portfolio investors.

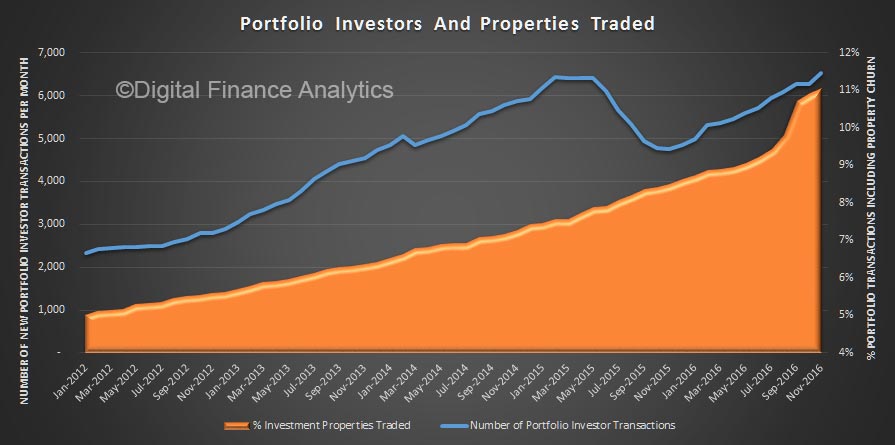

If we chart the proportion of portfolio investors who have sold an investment property, to buy another property, it has moved up from 5% in 2012, to 11% in 2016. These transaction means they are able to release net equity for future transactions, and offset capital costs in the process. Once again, portfolio investors in NSW are most likely to churn a property.

If we chart the proportion of portfolio investors who have sold an investment property, to buy another property, it has moved up from 5% in 2012, to 11% in 2016. These transaction means they are able to release net equity for future transactions, and offset capital costs in the process. Once again, portfolio investors in NSW are most likely to churn a property.

Our surveys also show portfolio investors are most likely to transact again in 2017, are most bullish on future home price growth, and will have multiple investment mortgages.

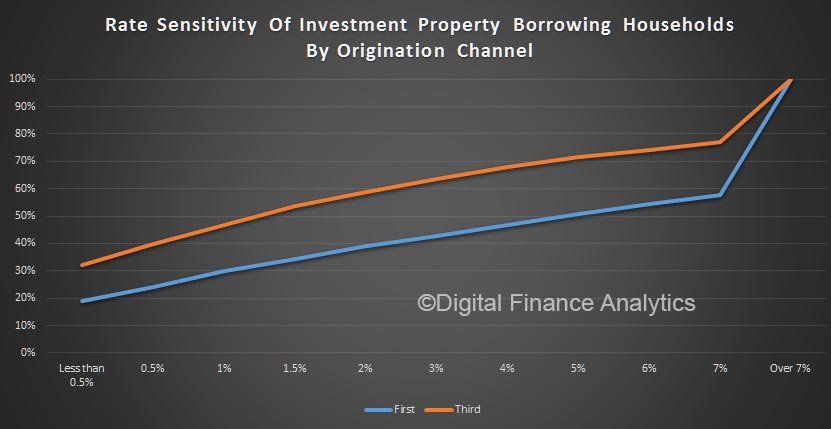

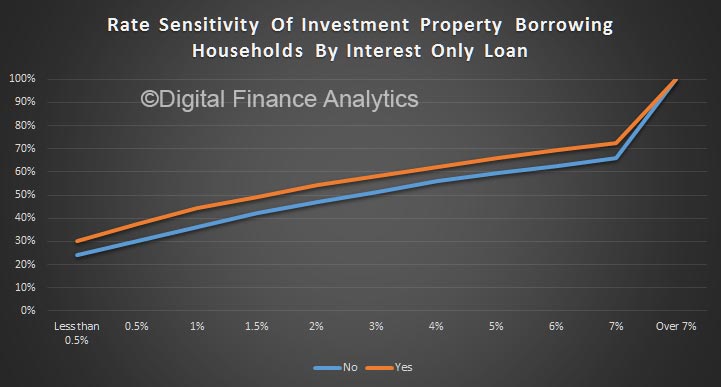

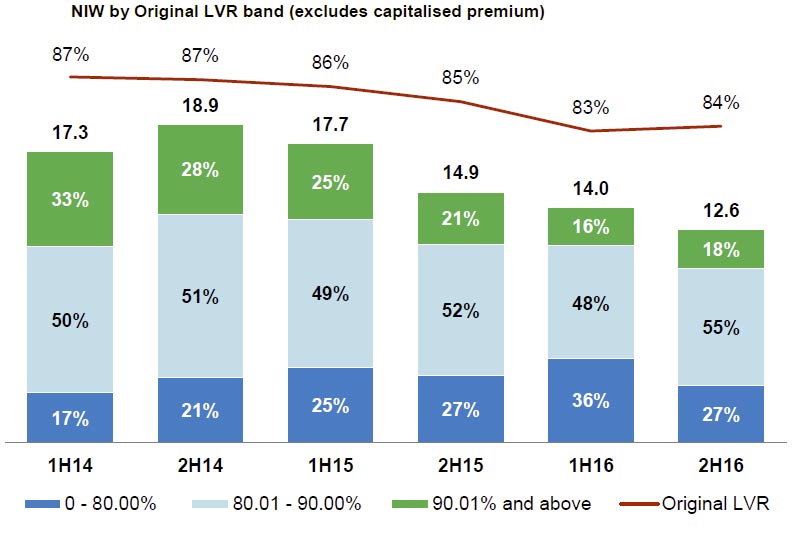

Significantly, many portfolio investors are using equity from one investment property to fund the next, and are reliant on rental income to service the mortgage. They often have multiple mortgages with different lenders. In addition, we found that many portfolio investors are using interest only loans, to keep loan servicing to a minimum and interest charges as high as possible for tax offset purposes.

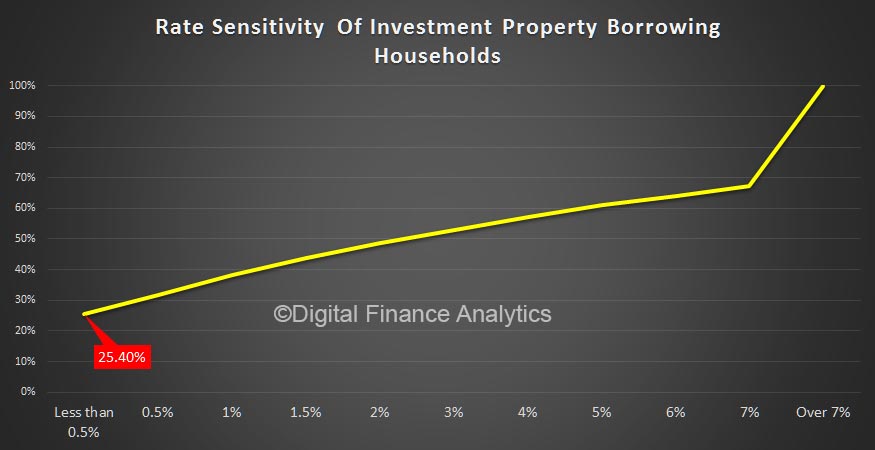

So long as property prices continue to rise, this highly-leveraged edifice will continue to generate high returns, which are, after tax, better than cash deposits or the share market. Of course the world would change if interest rates started to rise, capital values fell, or the banks clamped down on interest only loans. Overall, we think there are more risks in this sector of the market than are generally recognised.

In addition, we think there is a case to look harder at the tax breaks available to portfolio investors, and suggest that a cap on the number of properties, or value which can be so leverage should be considered. This is because as property values rise, tax-payers end up subsidising portfolio investors more than ever.

So, in summary, our analysis shows the market is being severely distorted, making homes less affordable, and shutting out many owner occupied purchasers who cannot compete. Risks are building, but meantime Property Portfolio Investors are having a field day!