The Banking Royal Commission is on, Housing credit is still growing strongly, and home prices in Sydney are slipping. So plenty to discuss in this week’s Property Imperative weekly to 2nd December 2017.

Watch the video, or read the transcript.

Watch the video, or read the transcript.

In this week’s review of finance and property news we start with the announced $75 million Royal Commission into Financial Services, which after lots of wrangling was announced this week. I will leave the politics alone, but as Fitch Ratings said, the inquiry into alleged misconduct adds challenges to the financial system and the findings could weaken the reputation of individual players, or possibly expose wider structural weaknesses.

So we think uncertainty about whether there will be an inquiry, and what scope it would cover, has been replaced by potential uncertainty of outcome. OK, the scope has been crafted to include a wide gamut of players, from banks, insurers and superannuation funds, but it is narrow because it will only look at misconduct against community expectations. It will touch on culture and governance (and this poses the question of the relationship between misconduct and culture) and it is tasked to make recommendations (but steering around other parallel work including the vertical integration which the Productivity Commission is looking at, and ACCC’s work on pricing). So it will likely focus on the well-trod paths of poor financial advice, bad insurance policy outcomes and inappropriate handling of SME’s when they get into financial difficulty. We hope the inquiry will specifically look at the various conflicts of interest which currently exist across the sector.

Credit and lending policies appear to be in scope, but we will have to wait and see whether they are explored, along with the role of financial advisers and mortgage brokers. The scope does not touch on broader policy or regulatory issues (such as macroprudential) but could conceivably cover lending standards and “liar loans”. One potential outcome could be to lift the lid on “not unsuitable” lending. It will not consider the disruptive intrusion from digital or Fintech.

What we can say is the banks and the Government clearly decided to cut their losses in the light of a potentially broader and more detailed scope which was being discussed on the back bench. This way they are controlling the agenda, at least to some extent. An interim report is expected next September.

Lots of economic news came out this week. The ABS Dwelling approvals for October were stronger than expected, reaching more than 19,000, the highest since August 2016. Growth in Victoria drove approvals higher up 3.8% – whilst there was a fall in New South Wales, down 0.3%. We are still seeing the strongest demand for property in VIC, thanks to strong migration, though supply and demand is patchy as the recent ANU study highlighted. Overall this suggest more property will continue to come on the market for sale, putting further downward pressure on prices.

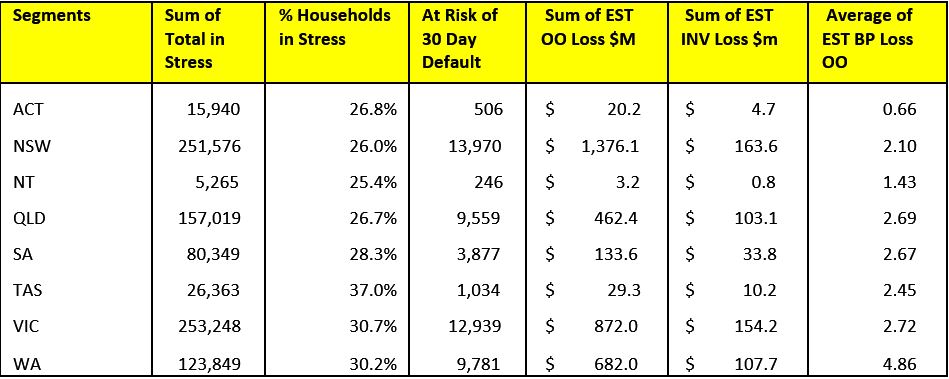

The RBA’s Credit Data for October showed that lending for housing rose 0.5% in the month, and 6.5% for the past year (three times inflation!). Lending to business rose 0.3% to 4% over the past year and personal credit was flat, and fell 0.9% over the past year. Another $1.2 billion of housing loans were reclassified in the month, making $60 billion in total, this is more than 10% of the total investment loan book! The proportion of investor loans fell slightly again, down to 34.2% of portfolio. Total mortgage lending is now above $1.7 trillion, with owner occupied loans up 0.6% or $6.6 billion to $1.12 trillion, and investor loans up 0.2% or $1.2 billion to $584 billion. Comparing this with the APRA data, we see continued relative growth in the non-bank sector.

The parallel ADI data from APRA to end October 2017 shows that banks continue to lend strongly to households. The overall value of their mortgage portfolios grew 0.5% in the month to $1.57 trillion, up $7.3 billion. Owner occupied loans grew 0.6% to $1.03 trillion, up $6.4 billion and investment loans rose 0.15% to $816 million. The proportion of investment loans continues to drift lower, but is still at 34.8% of all lending (too high!!). CBA reduced their investment portfolio this month, whilst Westpac grew theirs. Investor lending market growth is sitting at around 3% over the past year, though some smaller lenders are well above the APRA 10% speed limit.

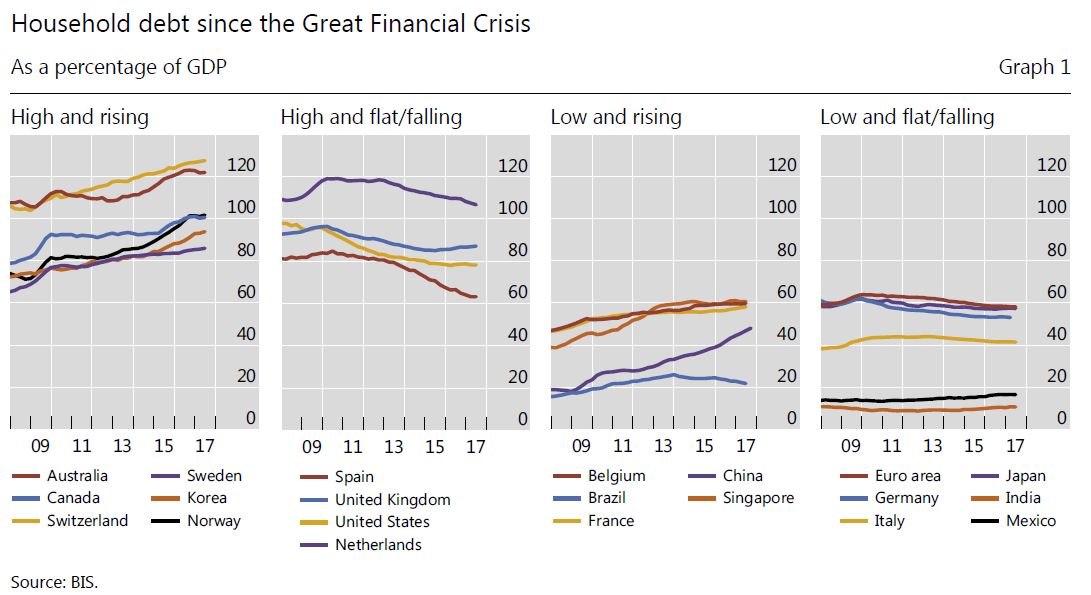

There is simply no excuse to allow home lending to be running at more than three times inflation or wage growth at the current dizzy price and leverage levels. There is still too much focus on home lending and not enough on productive growth enabling business lending. This is something which the Royal Commission is unlikely to touch, as it is a policy, not a behavioural issue.

The OECD report on Australia said things are looking better. As a result, they recommend rate hikes next year to help cool the housing market. But they call out a number of risks to economic growth and says macro-prudential measures should be maintained. Also their growth rates are lower than latest from the RBA! They also said Australia is vulnerable to “too big to fail” risks, due to its highly concentrated banking sector.

The Reserve Bank NZ has been more proactive on managing risks in the housing sector. They announced a slight reduction in tight loan to value lending controls, in response to slowing housing demand and new Government policies. The loan-to-value ratio (LVR) policy was first introduced in October 2013, with progressively tighter restrictions for investors introduced in November 2015 and October 2016. From 1 January 2018, the LVR restrictions will require that:

- No more than 15 percent (currently 10 percent) of each bank’s new mortgage lending to owner occupiers can be at LVRs of more than 80 percent.

- No more than 5 percent of each bank’s new mortgage lending to residential property investors can be at LVRs of more than 65 percent (currently 60 percent).

They had previously parked their Loan to Income initiative, in the light of easing momentum.

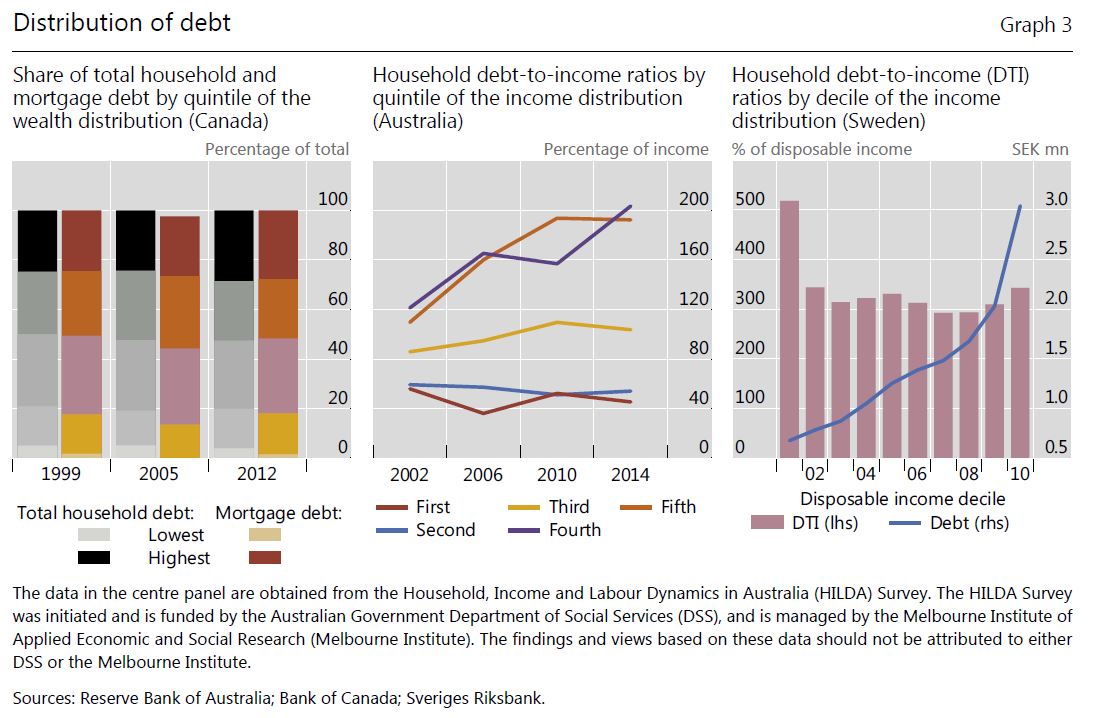

The Gratton Institute published a report which showed rising housing costs are hurting low-income Australians the most. Those at the bottom end of the income spectrum are much less likely to own their own home than in the past, are often spending more of their income on rent, and are more likely to be living a long way from where most jobs are being created. in 1981 home ownership rates were pretty similar among 25-34 year old’s no matter what their income. Since then, home ownership rates for the poorest 20% have fallen from 63% to 23%. Home ownership rates also declined more for poorer households among older age groups. Home ownership now depends on income much more than in the past.

They say that reducing demand – such as by cutting the capital gains tax discount and abolishing negative gearing – would reduce prices a little. But in the long term, boosting the supply of housing will have the biggest impact on affordability. To achieve this, state governments need to change planning rules to allow more housing to be built in inner and middle-ring suburbs.

So now to home prices. According to ME Bank, in a study of 1500 Australian adults, 43% of respondents said they were reliant on future house prices to achieve future life / financial goals, with 10% completely reliant. But it’s a tug-of-war as to which way we want prices to go: 38% want prices to increase while 37% want them to fall. Where you sit largely comes down to your property ownership status: 39% of those who own the home they live in and 47% who own an investment property indicated they are ‘reliant’ on future prices, presumably increasing, while 48% of those who don’t own a property also say they are reliant, presumably wanting prices to fall. Most tellingly, the survey indicates more Australians would benefit from property prices falling than rising, with only 28% indicating they’d benefit by selling if prices continued to rise compared to 47% who said they’d benefit by buying in if property prices fell.

But then again, according to CANSTAR nearly four out of five Australians don’t see house prices falling in their state over the next two years. CANSTAR surveyed 2,026 consumers on their views on property prices and home buying. Nationally, 47% of respondents expected steady growth in house prices, with a further 8% predicting prices would ‘skyrocket at some point’. Just 11% of respondents thought prices could fall in the next two years. Sydney was the most pessimistic city, with 16% predicting values would fall.

CoreLogic’s home price index reported a 0.1% fall nationally in November, with Sydney recording a 0.7% falls, along with falls across Darwin and regional Northern Territory, down 0.4% over the month. For the remaining broad regions of Australia, dwelling values were relatively steady, or experienced a subtle rise, over the month. However, the averages hide significant variations, with for example more expensive homes sliding further relative to cheaper ones. National dwelling values tracked 0.2% higher over the past three months and have increased 5.2% over the twelve months ending November. The national annual growth rate has now halved since reaching a recent peak in May 2017, when dwelling values rose 10.4%.

CoreLogic also says there were 3,409 homes taken to auction across the combined capital cities last week, returning a preliminary auction clearance rate of 66.9 per cent, overtaking the previous week as the third busiest for auctions so far this year. Last week, based on final results, 60.9 per cent of the 3,390 auctions held recorded a successful result, the lowest clearance rate since late 2015/early 2016.

But auction clearance rates may be lower than the CoreLogic figures suggest according to John Cunningham, president of the REINSW. Cunningham said that 40 per cent of results have not been reported, and if those results represent a no sale, then the clearance rate for Sydney could be a lot lower than the 66 per cent being reported by CoreLogic. With an initial clearance rate again in the mid 60 per cent range, the lack of clear data from the 40 per cent of unreported results fails to provide us with the real picture of the market,” he said.

More evidence of tighter lending standards, with CBA revealing a raft of changes including LVR caps and restrictions to rental income for serviceability that will impact mortgage brokers and their clients from next week. CBA will be introducing a new Home Loan Written Assessment document called the Credit Assessment Summary (CAS) for all owner occupied and investment home loan and line of credit applications solely involving personal borrowers. Meanwhile, CBA confirmed that it will introduce credit policy changes for certain property types in selected postcodes from Monday 4 December. They will reduce the maximum LVR without LMI from 80 per cent to 70 per cent, reducing the amount of rental income and negative gearing eligible for servicing and changing eligibility for LMI waivers including all Professional Packages and LMI offers for customers financing security types in some postcodes. “We continue to lend in all postcodes across Australia,” CBA said.

More rate cuts were announced this week, with Heritage Bank cutting the rate on new owner occupied loans by up to 50 basis points, and 30 basis points on new investment loans. They want to build and keep attracting new customers to the bank as part of a nationwide growth strategy. This will put more pressure on margins.

KPMG released their 2017 Mutuals Industry Review. Under the hood, the sector is under pressure, despite asset growth. COBA said they welcome the backing from KPMG, which highlighted strong financial performance. We are not so sure. Sure, assets are growing, but at what cost? KPMG says: profits before tax declined by 4.3 percent to $605.7 million. This compares to the major banks which saw profits grow by 7.6 percent. The net interest margin (NIM) continued to tighten and decreased to 2.03 percent, down 11 basis points. The increasing pressures on net interest margin is a result of historically low interest rates and increasing competition in the marketplace. Mutuals have sacrificed margins to maintain and grow the membership base. The average capital adequacy ratio dropped 30 basis points to 17.2 percent in 2017, representing a decline in capital levels for the fourth consecutive year. This reflects the increasing prioritisation of effective capital use by mutuals. As limited equity funding is inherent within the mutuals’ current business model and capital growth through new profits have been constrained this year, mutuals have looked to existing capital bases to fund balance sheet growth.

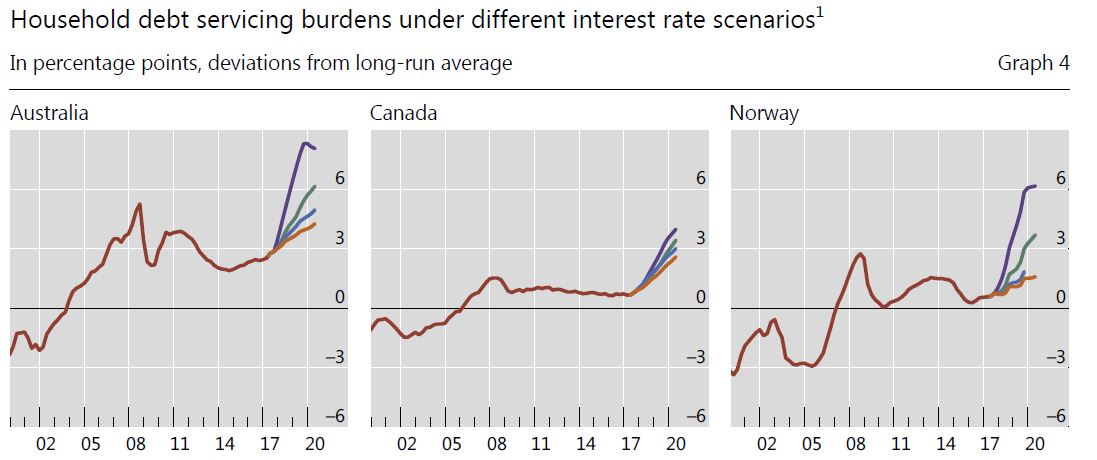

We think the Royal Commission will tend to drive international funding costs higher (they were already going higher), and as banks have around 30% of their books funded offshore, this will put more pressure on margins and local mortgage rates. In addition, we are still forecasting a cash rate hike next year, so more pressure on mortgage rates there. At the same time lending standards continue to be tightened, so borrowers will need a larger deposit especially in some higher risk areas. Mortgages are set to become more expensive and harder to get. Also, more new property is set to come onto the market, and as home price momentum eases, this will tend to push prices lower. So we can suggest several reasons why prices will go lower, but non to make them rise. So on that basis, the 80% of households expecting prices to keep rising are in for a rude awakening.

And that’s the Property Imperative weekly to 2nd December 2017. If you found this useful, do leave a comment or subscribe to receive future updates. Check back next week for our latest update, which will include November Mortgage Stress results. Many thanks for taking the time to watch.

Income is at the heart of access to services and opportunities, which are differing and unequal based on where you live.

Income is at the heart of access to services and opportunities, which are differing and unequal based on where you live.