From The Conversation.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) may be underestimating Australian household energy bills by 25% because of a lack of accurate data from the federal government.

The Paris-based IEA produces official quarterly energy statistics for the 30 member nations of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), on which policymakers and researchers rely heavily. But to provide this service, the IEA relies on member countries to provide it with good-quality data.

Last month, the agency published its annual summary report, Key World Statistics, which reported that Australian households have the 11th most expensive electricity prices in the OECD.

But other studies – notably the Thwaites report into Victorian energy prices – have reported that households are typically paying significantly more than the official estimates. In fact, if South Australia were a country it would have the highest energy prices in the OECD, and typical households in New South Wales, Queensland or Victoria would be in the top five.

A spokesperson for the federal Department of Environment and Energy, the agency responsible for providing electricity price data to the IEA, told The Conversation:

Household electricity prices data for Australia are sourced from the Australian Energy Market Commission annual Residential electricity price trends report. The national average price is used, with GST added. It is a weighted average based on the number of household connections in each jurisdiction.

The Australian energy statistics are the basis for the Australia data reported by the IEA in their Key world energy statistics. The Department of the Environment and Energy submits the data to the IEA each September. Some adjustments are made to the AES data to conform with IEA reporting requirements.

But it is clear that the electricity price data for Australia published by the IEA is at least occasionally of poor quality.

The Australian household electricity series in the IEA’s authoritative Energy Prices and Taxes quarterly statistical report stopped in 2004, and only resumed again again in 2012.

Between 2012 and 2016, the IEA’s reported residential price series data for Australia showed no change in prices.

Yet the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ electricity price index, which is based on customer surveys, showed a roughly 20% increase in the All Australia electricity price index over this period.

Australia is also the only OECD nation not to report electricity prices paid by industry.

Current prices

This year’s reported household average electricity prices are almost certainly wrong too. The IEA reports that household electricity prices in Australia for the first quarter of 2017 were US20.2c per kWh.

At a market exchange rate of US79c to the Australian dollar, this puts Australian household electricity prices at AU28c per kWh. Adjusted for the purchasing power of each currency, the comparable price is AU29c per kWh.

By contrast, the independent review of the Victorian energy sector chaired by John Thwaites surveyed the real energy prices paid by customers, as evidenced by their bills. In a sample of 686 Victorian households, those with energy consumption close to the median value were paying an average of AU35c per kWh in the first quarter of 2017. This is 25% more than the IEA’s official estimate. At least part of this difference is explained by the AEMC’s assumption that all customers in a competitive retail market are supplied on their retailers’ cheapest offers. But this is not the case in reality.

Surveying real electricity and gas bills drastically reduces the range of assumptions that need to be made to estimate the price paid by a representative customer. Indeed, as long as the sample of bills is representative of the population, a survey based on actual bills produces a reliable estimate of representative prices in retail markets characterised by high levels of price dispersion, as Australia’s retail electricity markets are.

Pointing to a reliable estimate of Victoria’s representative residential price is, of course, not enough to prove that the IEA’s estimate is wrong. It could just as easily mean that Victorians are paying way more than the national average for their electricity.

But the idea that Victorians are paying more than average does not stack up when we look at the state-by-state data, which suggests that Victoria is actually somewhere in the middle. Judging by the prices charged by the three largest retailers in each state and territory, Victorian householders are paying about the same as those in New South Wales and Queensland, less than those in South Australia, and more than those in Tasmania, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and the Australian Capital Territory.

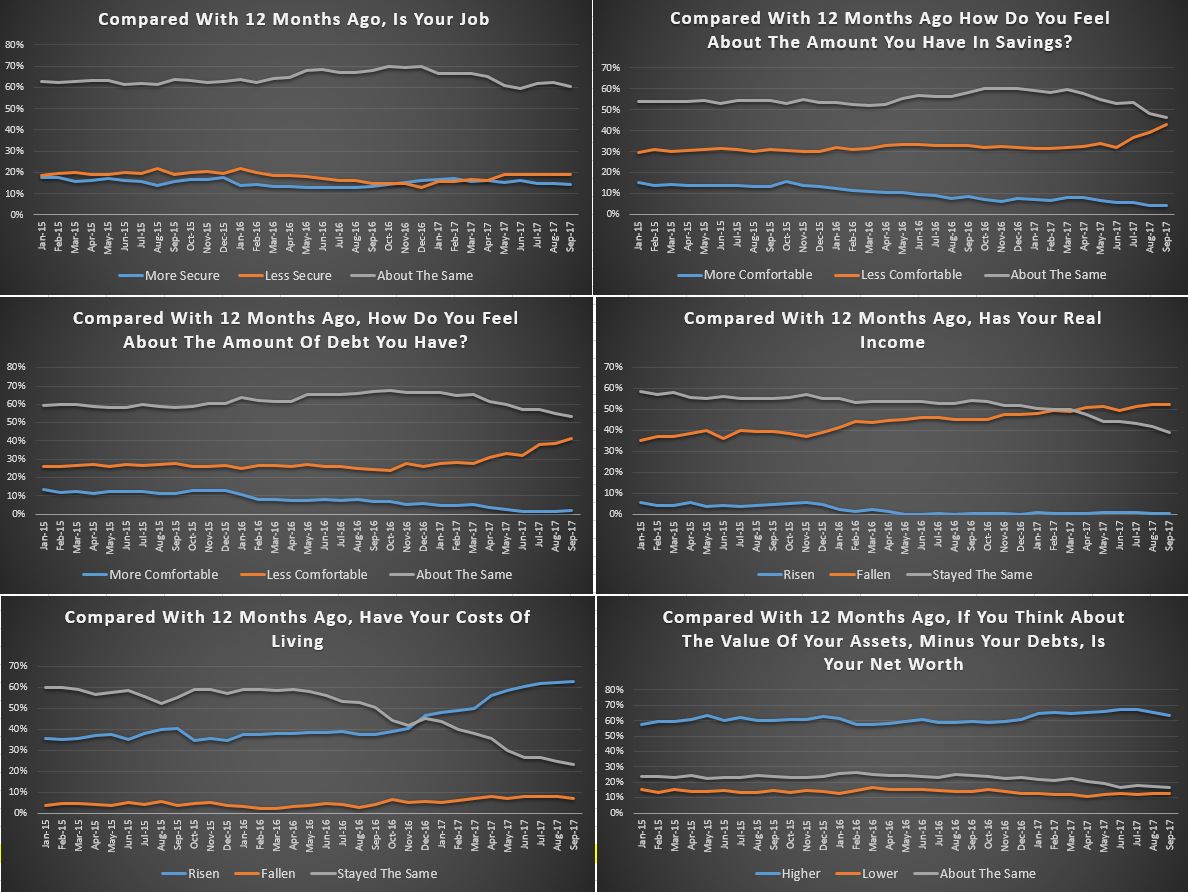

Residential electricity prices. Author provided

Residential electricity prices. Author provided

The IEA can not reasonably be blamed for the inadequate residential data for Australia that they report, and the nonexistent data on electricity prices paid by Australia’s industrial customers. The IEA does not do its own calculation of prices in each country, but rather it relies on price estimates from official sources in those countries.

An obvious question that arises from this is where Australia really ranks internationally if we used prices that reflect what households are actually paying.

This is contentious, not least because prices in New South Wales, Queensland and South Australia increased – typically around 15% or more – from July this year. We do not know how prices have changed in other OECD member countries since the IEA’s recent publication (which covered prices for the first quarter of 2017). But we do know that prices in Australia have been far more volatile than in any other OECD country.

Assuming that other countries’ prices are roughly the same as they were in the first quarter of 2017, our estimate using the IEA’s data is that the typical household in South Australia is paying more than the typical household in any other OECD country. The typical household in New South Wales, Queensland or Victoria is paying a price that ranks in the top five.

It should also be remembered that these prices are after excise and sale tax. Taxes on electricity supply in Australia are low by OECD standards – so if we use pre-tax prices, Australian households move even higher up the list.

There are serious question marks over Australia’s official electricity price reporting. Policy makers, consumers and the public have a right to expect better.

Author: Bruce Mountain, Director, Carbon and Energy Markets., Victoria University