Within the political class there is a low level moral panic about low wages growth. The irony is that those lamenting this situation are simply witnessing the ultimate outcome of policies they have long advocated.

While Australia still has systems like Industrial Tribunals and Awards – given how they interact with market forces today, these institutions now work to entrench wage inequality rather than reduce it.

Wage rates and movements are determined by a combination of market and institutional forces. Technology, human capital, levels of labour supply and the profitability of companies in laggard and leading set the lower and upper bounds for sustainable wage levels.

As economist and philosopher Adam Smith noted, the income workers require to survive sets what’s called a “market floor” for wages – the lowest acceptable limit. Rates of profit in the best performing firms set the upper limit, as Australia’s executive class has shown very clearly for over three decades now. What rates actually prevail within these very broad limits are determined by institutional forces – in Australia, the award system of minimum wages and unions collective bargaining rights.

Historically Australia has had the great benefit of having institutional arrangements that balanced these forces well. The key elements of this were a network of industrial tribunals that regularly assessed the overall economic and social situation and determined what rates and movements in pay were sustainable.

These rates were not set unilaterally, but in coordination with what employers and organised workers indicated was possible, in industry level collective agreements.

The defacto rule was that wage movements should equate to movements in productivity plus the cost of living. The standards set in the leading profitable sectors then spread to the entire workforce through the maintenance of award relativities (ie standard comparative rates of pay set by reference to benchmark occupations like metal fitter, carpenter and truck driver). During this time awards rates approximated pretty closely to going rates of pay.

These underlying principles were not unique to Australia. In the era following the second world war it meant that in most countries workers shared in productivity growth and wages tracked pretty closely with it.

Since the mid 1970s and especially since the 1980s all this has changed.

Australia has not seen anything like full employment since the early 1970s. While unemployment has been cyclical, it has usually been 5% or more since that time. More importantly, underemployment has been on the rise.

This has not been cyclical. It has racketed up after each recession.

And that is just in terms of hours worked. If we took into account workers with skills not being used, levels of labour underutilisation are much higher. Estimates of underutilisation of this nature vary as being between 15 and 25%.

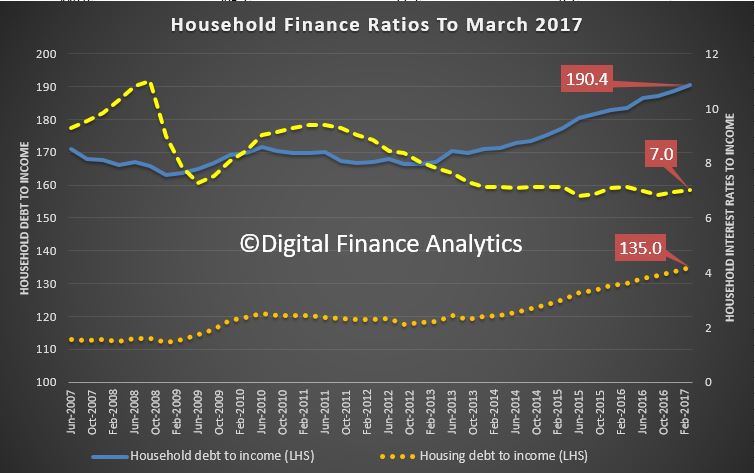

High levels of indebtedness also weaken workers bargaining power. Today few can hold out for long bargaining periods – either individually or collectively. This gives employers a huge advantage in setting wages.

The legacy of labour market ‘reform’

In the 1970s and 1980s Australia’s wage setting institutions worked well to protect wage rates against the full force of these downward pressures. Since the early 1990s, however, those institutions have been transformed.

The key issue here has not just been the weakening of unions and their bargaining power. Just as significant has been the uncoupling of wage rates set by wage leaders, from the wages of the weak. Workers in benchmark setting sectors like construction used to establish wage norms. These were recognised by industrial tribunals as a community standard which they then passed on to workers in weaker sectors like retail through generalised award wage base rises. In this way the wages of the strong supported movement in the wages of the weak.

This was a key “reform” of the Keating government, introduced with the active support of the ACTU. It was explicitly designed to let wages of the strong grow faster than the wages of the weak to maintain macroeconomic balance as the wages system decentralised.

The Howard governments’ labour law changes – first the Workplace Relations Act (1996) and then Workchoices (2006) – merely extended the logic of this reform trajectory. The current Fair Work Act merely codifies this trajectory as the law of the land today.

Today Austraila’s minimum wages remain among the highest in the world. The difference is they operate in relative isolation from the rest of the workforce.

Until the 1990s they were part of an interconnected system that ensured wages gains of the strong were widely shared. Today they provide the ultimate safety for those with the weakest levels of bargaining power – currently about 15% of the workforce directly and a further 15% indirectly.

We should also not forget the new found role of Treasury departments. Immediately after its election, the O’Farrell government in NSW legislated to cap wage rises in the NSW public sector to no more than 2.5% per annum.

Pubic sector teachers and nurses, especially in NSW, were emerging at the new wage leaders. This meant that their wages were now capped and this Treasury edict – and not collective bargaining and arbitration – set community wage norms.

Today our wages system has a different logic. The recent cut in penalty rates is a case of the wages of the weak putting pressure on the wages of the strong. While the Fair Work Commission quarantined the rest of the workforce from this cut by limiting its recent decision to low paid service workers – the precedent is there. Future movement in wage standards for anti-social hours will be down and not up.

Over the course of the twentieth century Australia devised a remarkable set of institutions to manage the complex problem of wages and labour standards. It’s time we built on what little remains of that legacy to remedy low wage growth.

Building on these institutions doesn’t mean restoring what was. New policies need to engage with new realities. Even former enthusiastic supporters for reducing labour standards and wages such as the IMF now recognise growth needs to be inclusive if it is to sustainable.

It’s much easier to destroy institutions that deliver fair pay than build them. Australia found ways of achieving fair pay over the course of the twentieth century – it can to so again.

Author: John Buchanan, Head of the Discipline of Business Analytics, University of Sydney Business School, University of Sydney