There is much discussion of mortgage stress, some of which we highlight by our ongoing research into the growing numbers of households under financial pressure. The results for July will be out soon.

But rental stress is less discussed, but in our mind is equally significant, so today we explore some of the data in our Core Market Model to July 17. In fact there are more households in rental stress than in mortgage stress according to our analysis. We know their financial confidence on average is lower.

First, we need to define rental stress. Whilst some will use a “30% of income to pay the rent” as a benchmark, we do not think it is an adequate measure – not least because we see large numbers of households renting where more than 30% of income is paid away on rent, yet they are not in financial difficulty. Others pay less away, but are in stress. 30% is too arbitrary!

So we look at net cash flow. If households, once they pay their rent, tax and other outgoings have close to nothing left, or a small deficit, at the end of the month, they fall into our mild stressed category. Those with a severe cash deficit at the end of the month, are in serve stress.

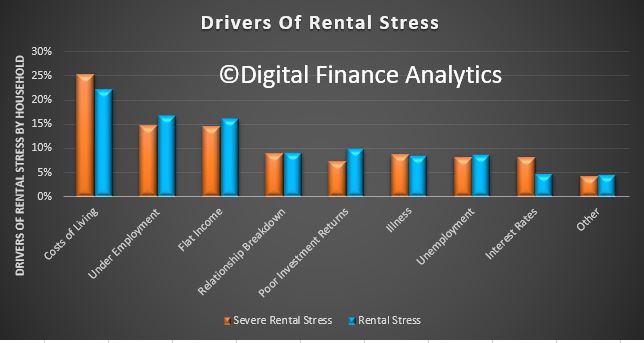

We start by looking at the causes of rental stress. Using data from our surveys, we find that costs of living, under employment and flat incomes are the main causes of rental stress.

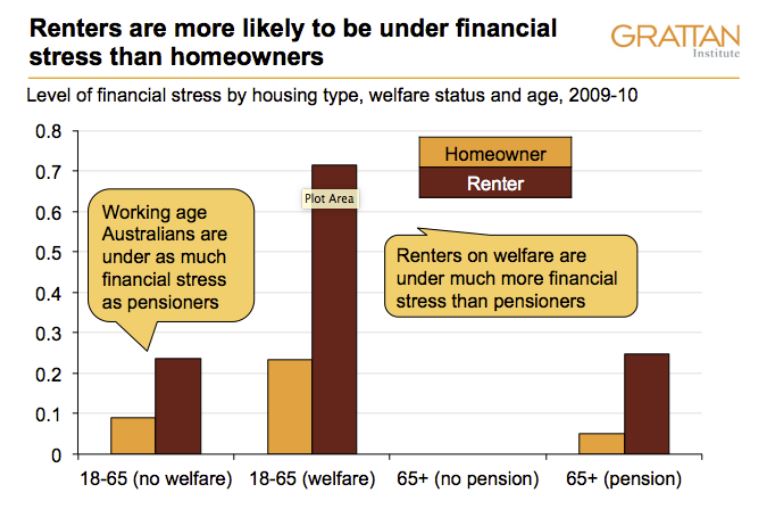

Those renting tend to hold less financial assets, so are more exposed, especially where they are also responsible for bills (electricity, council rates etc). Those in difficulty will be more likely to hold multiple credit cards, and also access short term loans to get by. Those in the stressed categories will be less likely to spend at the shops, and so are a brake on economic activity. One strategy some use is to move to cheaper rented accommodation, with poorer facilities to reduce outgoings. The migratory nature of renters, especially those in stress are not well understood. The current tenancy regulations in Australia are pretty weak. Much of this movement is not reported, nor recorded.

Those renting tend to hold less financial assets, so are more exposed, especially where they are also responsible for bills (electricity, council rates etc). Those in difficulty will be more likely to hold multiple credit cards, and also access short term loans to get by. Those in the stressed categories will be less likely to spend at the shops, and so are a brake on economic activity. One strategy some use is to move to cheaper rented accommodation, with poorer facilities to reduce outgoings. The migratory nature of renters, especially those in stress are not well understood. The current tenancy regulations in Australia are pretty weak. Much of this movement is not reported, nor recorded.

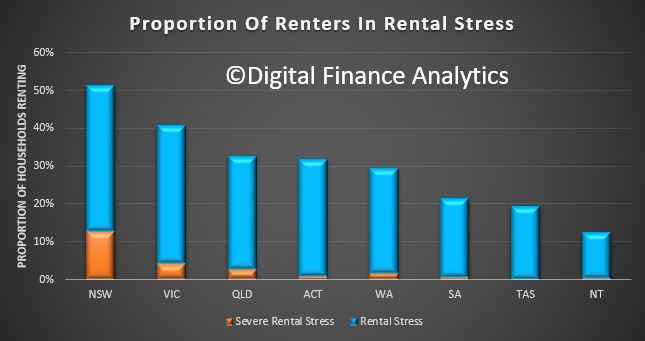

So, lets look at some of the numbers, remembering one third of households are renting, in round numbers that is 3 million households.

Looking by state, more than half of renters in NSW are in rental stress (on our definition), and the highest proportion of any state here are in severe rental stress. The proportion of households in stress fades away as we look across the other states and territories. But the three most populous states have the highest rental stress levels.

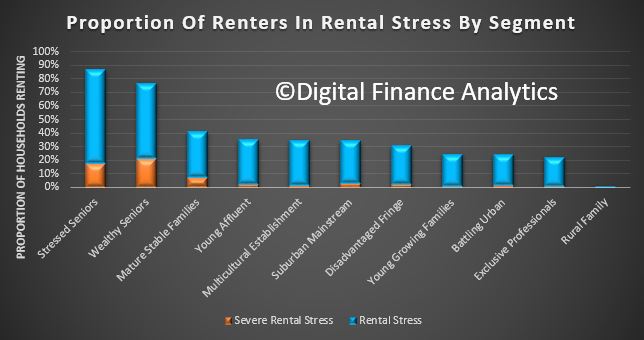

Looking across our segments, we see that older households are more under stress, and a significant proportion in severe stress. Whilst wealthy seniors may hold some savings, stressed seniors do not. Many are reliant on Government support.

Looking across our segments, we see that older households are more under stress, and a significant proportion in severe stress. Whilst wealthy seniors may hold some savings, stressed seniors do not. Many are reliant on Government support.

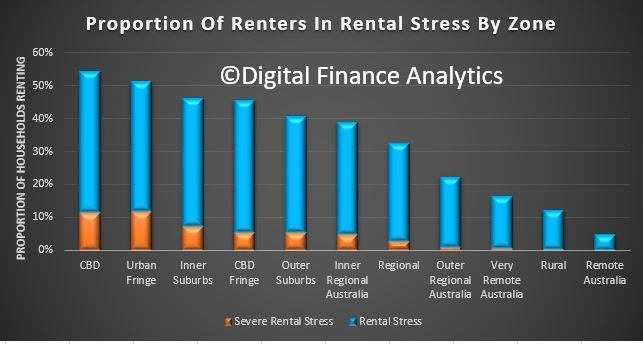

Looking across the geographic zones (a series of concentric rings around our main urban hubs) we see significant levels of stress in the urban centres, as well as on the urban fringe. The former is being created by high rents – especially in the newly constructed high-rise blocks being thrown up across the eastern states, often occupied by young affluent households; whilst in the urban fringe, it is more about depressed incomes. We see stress rolling out into the regions, but is less apparent in the more rural and remote areas.

Looking across the geographic zones (a series of concentric rings around our main urban hubs) we see significant levels of stress in the urban centres, as well as on the urban fringe. The former is being created by high rents – especially in the newly constructed high-rise blocks being thrown up across the eastern states, often occupied by young affluent households; whilst in the urban fringe, it is more about depressed incomes. We see stress rolling out into the regions, but is less apparent in the more rural and remote areas.

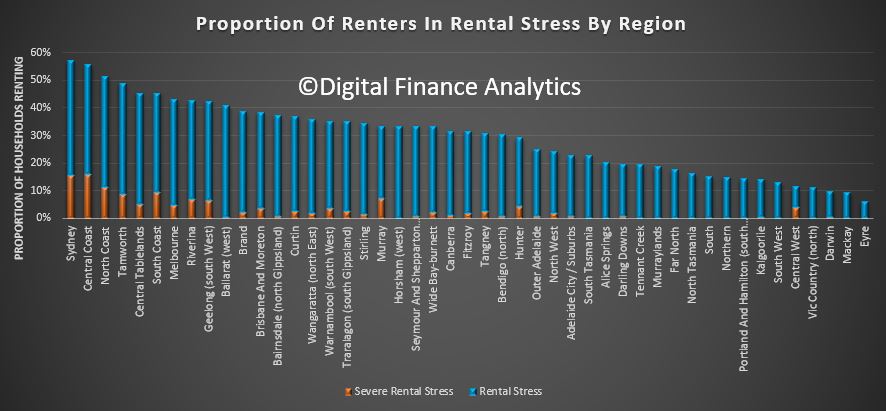

Finally, here is list of the regions across the country. Greater Sydney and the Central Coast have the highest representation of stressed renters as a proportion of all households renting.

Finally, here is list of the regions across the country. Greater Sydney and the Central Coast have the highest representation of stressed renters as a proportion of all households renting.

All this highlights the issues we have due to the combination of flat incomes, and rising costs. It is also the obverse of the picture we revealed yesterday, where we showed rental growth is very low (causing more investors to have a net cash-flow problem).

All this highlights the issues we have due to the combination of flat incomes, and rising costs. It is also the obverse of the picture we revealed yesterday, where we showed rental growth is very low (causing more investors to have a net cash-flow problem).

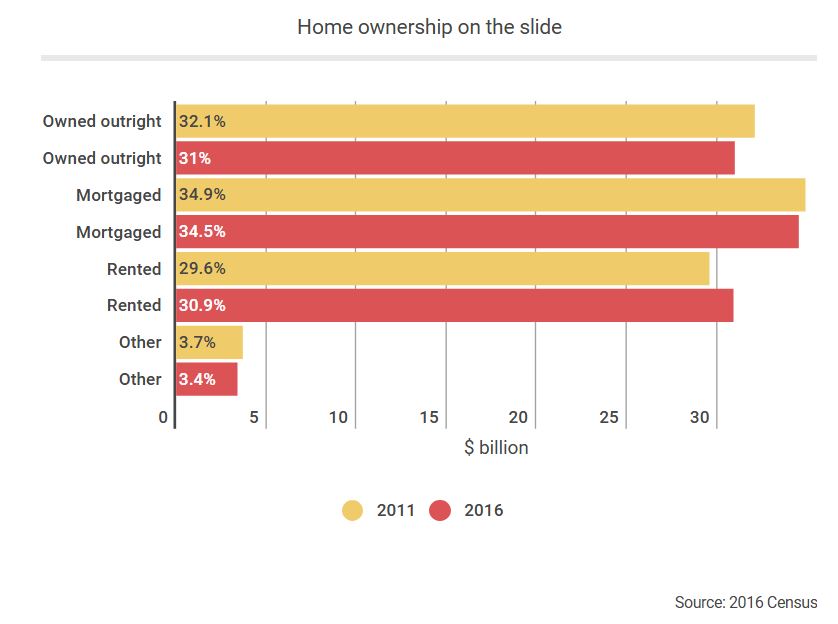

Once again we see the outworking of poor public policy over a generation. With an internationally high proportion of property investors and a high proportion of people who are likely to never own their own property, rental stress provides another important perspective of the issues we face.

We have very granular data, down to post code, but that will get too detailed for this post.