More than 600,000 low-wage workers in the services sector will suffer a wage cut on the first day of next month, after a judicial bench refused pleas to cancel or delay cuts to penalty rates.

In a decision handed down on Monday, the Fair Work Commission denied requests from unions for the wage cuts to be postponed for two years or, at the very least, for currently employed Australians to be quarantined from the cuts.

Instead, the Commission chose to stagger the cuts to Sunday loadings, which means workers will have their wages cut every year on July 1 until 2019 or 2020, depending on their industry.

The verdict applies to workers paid Award rates in the hospitality, fast food, retail and pharmacy sectors.

ACTU secretary Sally McManus urged Parliament to legislate against the “devastating” cuts.

“This can be stopped. Our Parliament can stop it. Malcolm Turnbull can stop it,” she told reporters.

“There is a bill before Parliament as we speak and it can be voted on in the next two weeks and bring a stop to these penalty rate cuts.

“These cuts are devastating. It’s $70 a week in total on average for workers. These are the lowest paid workers in our community.”

Employer groups had urged the Commission to not phase in penalty rate cuts at all, arguing this would boost employment sooner.

The Commission dismissed this argument by acknowledging it was “cautious” about any boost to employment flowing from lower rates of pay. Instead, it argued that workers would benefit from “an increase in overall hours worked”.

However, it did decide to impose the public holiday penalty cuts all at once, from July 1, 2017.

Ms McManus disagreed, telling The New Daily that workers would end up “working longer for less pay”.

From July 1, Sunday penalty rates will be cut by 5 percentage points across the four sectors for full- and part-time workers, bringing penalty rates to 145 per cent for fast food; 195 per cent for pharmacy and retail; and 170 per cent for hospitality.

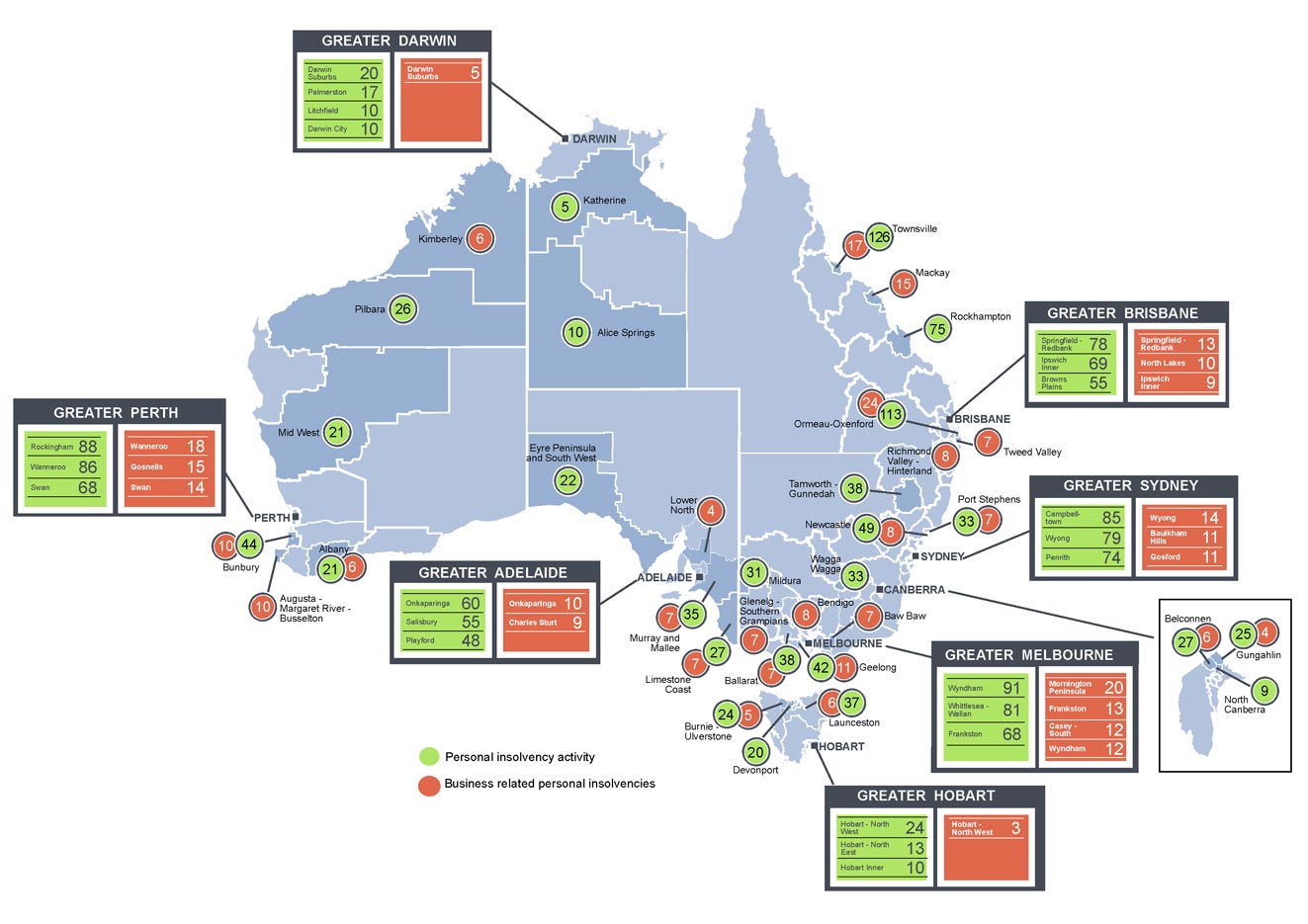

The McKell Institute, commissioned by the ACTU, has calculated, based on 2011 census data, that if the Sunday penalty rate cuts had been implemented in full on July 1, roughly 621,000 workers would have lost $1.4 billion in disposable income a year, with rural and regional areas the worst hit.

Some, such as Warren Entsch, Liberal MP for the worst affected electorate of Leichardt, have dismissed these numbers as exaggerated.

But even if the disposable income and affected worker numbers were overstated by the McKell Institute’s methodology, it would not affect the rankings. Rural and regional workers would remain the worst hit.

The Australian Industry Group said the Commission’s decision was “fair”, but that it would have preferred for the cuts to be implemented straight away, not phased in.

Rob Mitchell, Labor MP for Australia’s second-worst affected electorate, told The New Daily that penalty rates are important because weekend workers “are missing out on what we value in Australia”.

“I know from my experience when I was with the RACV, having to work on Christmas Day and doing weekend work on both day shifts and night shifts, how this had a big impact on family life and the loss of participation in special family occasions,” Mr Mitchell said.

“This cut attacks the young, it attacks the vulnerable. The FWC does its work, and in this case it got it wrong – very badly wrong.”

Mr Mitchell was especially concerned about the impact of the cuts on consumer spending.

“For many in our communities, these cuts will mean that people have less discretionary spend. If they’ve got less discretionary spend, they’re going to be tightening things up, they won’t be going to restaurants or to the shops, so you could actually see a contraction in small town economies.”

How the changes will be phased in: