When it comes to the housing debate, there’s one number that just won’t go away: 20 per cent.

Many fear that’s how much they’ll have to save for a deposit. It’s easy to understand why – popular measures of affordability, such as those compiled by CoreLogic and CoreData, often assume a 20 per cent lump sum.

Except it’s not.

Back in 2015, the Reserve Bank noted: “the deposit required of a first home buyer is no longer necessarily around 20 per cent of the purchase price, but rather, more often in the 5–10 per cent range.”

Regulators have tightened the screws since then, but there are still mortgages with below 20 per cent deposits to be found, according to Dr Ashton De Silva from RMIT’s Centre for Urban Research.

He said homebuyers taking out bigger loans should consider the benefits of getting into the housing market now, rather than waiting to reach a certain deposit.

“It’s not just a case of working out that you’ve got to pay another $50,000 in interest. What is the economic benefit of securing that place now?” Dr De Silva told The New Daily.

“We expect people are making the decision that: ‘It is better for me to take on that extra cost and secure this dwelling.’”

Two Australians earning the average full-time wage, with average living costs, will likely qualify for a loan just over $1 million with one of Australia’s big banks.

Finder, a financial comparison website, lists a bevy of acronyms that offer low deposit loans, including: NAB, ME, CUA, IMB and HSBC.

Many lenders have created new financial products to help homebuyers enter the market, resulting in Australia having, according to Dr De Silva, “one of the most product diverse markets in the world”.

One option is lenders’ mortgage insurance, which lowers required deposits to a minimum of 5 per cent, meaning purchasers of a $500,000 property can require a lump sum of only $25,000.

Mortgage insurance is usually paid as a one-off charge, with the cost calculated as a percentage of the loan amount and based on the size of your deposit.

Occasionally, it can even be ‘capitalised’ into the value of the loan – which means you borrow more to cover the cost of the insurance. If you do this, you’ll pay slightly higher repayments, rather than a big sum up front.

It’s important to note the insurance only protects the lender against the risk of you defaulting on the mortgage, not you.

You need $200,000 to meet the 20 percent deposit on a $1 million dollar mortgage, an enormous sum for most Australians.

With mortgage insurance, a couple taking out a loan with a 5 per cent deposit would need $50,000, plus the cost of the insurance.

Some lenders won’t charge insurance on loans with a 10 per cent deposit, but this depends on job security and credit history.

Two Australians earning the average full-time wage, with average living costs, will likely qualify for a loan just over $1 million with one of Australia’s big banks.

Dr De Silva warned home buyers should do their homework and weigh up the costs and benefits of different loans.

“One thing that needs to be at the forefront is, ‘Can I afford to ride out any crisis that may arise?’”

Associate Professor Chyi Lin Lee, an expert in property market economics at the University of Western Sydney, pointed to 20 per cent deposits as a main source of difficulty for many homebuyers.

“We need to find an innovative way to help owner-occupiers to get into the market,” he told The New Daily.

Professor Lee said schemes which help homebuyers jump over the deposit hurdle – such as controversial first homebuyer grants – can be successful, despite the upward pressure they put on prices.

A caution: don’t overextend

Professor Lee warned lower deposits shouldn’t be an excuse for buyers to take out bigger loans than they can pay off.

This was backed by Dr Rachel Ong, deputy director at the Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre, who said people taking out loans with low equity can expose themselves to higher repayments.

“It isn’t a good idea to try and lower the minimum deposit because there’s people who might not be able to meet the payments, and the consequences of that are all the negative and quite severe,” Dr Ong said.

“There’s a reason why the minimum deposit is set at what it is.”

Category: Social Trends

First home buyer demand bounces higher

Low rates combined with recent changes to various first home buyer initiatives has helped encourage more potential property buyers into the market, new research has revealed.

Mortgage Choice’s latest Loan Purpose Report found first home buyers accounted for 14% of all loans written by the company in April, up from 12.2% in January.

“In the first quarter of 2017, we saw a rise in the number of first home buyers taking out loans through Mortgage Choice,” Mortgage Choice chief executive officer John Flavell said.

“This growth in first home buyer demand can be attributed to a number of factors, including low interest rates, stagnating property price growth and enhanced first home buyer incentives.

“In the first instance, property prices have started to stagnate across the country, with CoreLogic data showing the median dwelling value in Australia rose just 0.1% over the month of March.

“Furthermore, interest rates remain at historical lows, which has helped keep the cost of borrowing at affordable levels.

“In addition, some states have made changes to their various first home buyer incentives over the first quarter of 2017.

“In Western Australia, the Government announced a temporary $5,000 boost to the First Home Owners Grant. The boost payment is available to eligible first home buyers who enter into a contract between 1 January and 30 June 2017 to purchase or construct a new home, and owner builders who commence laying foundations of their home between those dates.

“As a result of all of these factors, we have seen a slight uptick in the total level of first home buyer demand.”

Looking ahead, Mr Flavell said he wouldn’t be surprised to see first home buyer demand increase further as potential buyers look to take advantage of the low rate environment and various home buyer incentives soon to be on offer.

“In Victoria, some first home buyers will soon be given access to a $20,000 boosted grant. Those purchasing or constructing new homes in regional Victoria will be eligible for the grant.

“In addition, from 1 July 2017, first home buyers purchasing a home with a dutiable value of no more than $600,000 will not have to pay stamp duty – which can be a real financial impost for many first home buyers.

“These two initiatives alone are likely to encourage more first home buyers in Victoria – especially regional Victoria – onto the property ladder.”

But while Mr Flavell said he wouldn’t be surprised to see first home buyer demand climb slightly higher in places like Victoria, he said more still needs to be done by the other states and territories to help this home buyer group.

“While we have seen a slight improvement in first home buyer demand over the first few months of the year, total first home buyer demand remains very low.

“In April 2014, first home buyers made up 17.8% of all loans written through Mortgage Choice. Today, that percentage has slumped to just 14%.

“We believe more needs to be done to help first home buyers get onto the property ladder.

“The Federal Government announced earlier this month that it would allow first home buyers to salary sacrifice part of their income into their superannuation account in order to help them build their property deposit faster.

“While this initiative is great in theory, it is unlikely to have a huge impact. At best, a couple who salary sacrifice a portion of their income into their super might be able to scrape together enough money to pay for the stamp duty charged in markets like Sydney.

“Indeed, there is nothing to suggest that this new scheme will deliver a different result to the spectacularly unsuccessful First Home Saver Account initiative that was launched by the Rudd Government in 2008 and withdrawn from the market in 2014.”

Digital Finance Analytics – Quenching The Thirst For Accurate Household Mortgage Data

Digital Finance Analytics Core Market Model is now being used by a growing number of financial services companies and agencies who want to understand the true dynamics of the current mortgage market and the broader footprint of household finances across Australia.

The DFA Approach

By combining our household survey data, with private data from industry participants as well as public data from government agencies we have created a unique statistically optimised 52,000 household x 140 field resource which portrays the current status of households and their financial footprint. Because new data is added to each week, it is the most current information available. We also estimate the extent of future mortgage defaults, thanks to the data on household mortgage stress.

Posts on the DFA blog uses data from this resource. Momentum in our business has picked up significantly as concerns about the state of household finances grow and the thirst for knoweldge grows. We plug some of the critical gaps in the currently available public data which is in our view both limited and myopic.

A Soft Sell

The complete data-set is available purchase, either as a one-off transaction, or by way of an annual subscription which includes the full current data plus eleven subsequent monthly updates.

Other clients prefer to request custom queries which we execute on a time and materials basis.

In this video you can see an example of the core model at work. We show how data can be manipulated to get a granular (post code and segment) understanding of the state of play. This is important when the situation is so variable across the states, and across different household groups.

We Hold Granular Data

- Household Demographics (including age, education, structure, occupation and income, location, etc.)

- Household Property Footprint (including residential status, type of property, current value of property, whether holding investment property, purchase intentions, etc.)

- Household Finances (including outstanding mortgages and other loans, credit cards, transaction turnover, deposits, superannuation and SMSF, and other household spending)

- Household Risk Assessment (including loan-to-value, debt servicing ratio, loan-to-income ratio, level of mortgage stress, probability of default, etc.)

- Household Channel Preferences (including preferred channel, time on line, use of financial adviser, use of mortgage broker, etc.)

- Segmentation (derived from our algorithms; for household, property, digital and others)

Request More Information

You can get more information about our services by completing the form below, where you can also request access to our Lexicon which describes in detail the data available.

You should get confirmation your message was sent immediately and you will receive an email with the information attached after a short delay.

Note this will NOT automatically send you our ongoing research updates, for that register here.

[contact-form to=’mnorth@digitalfinanceanalytics.com’ subject=’Request Details of DFA Core Market Model’][contact-field label=’Name’ type=’name’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email’ type=’email’ required=’1’/][contact-field label=’Email Me The Information’ type=’radio’ options=’Yes Please’ required=’1′ /][contact-field label=’Email Me The Lexicon (option)’ type=’radio’ options=’Yes Please’ required=’0′ /][contact-field label=’Comment If You Like’ type=’textarea’/][/contact-form]

The ‘jobs growth’ myth leading us to breaking point

When the ratings agency S&P Global downgraded its outlook for the Australian economy earlier this week, it would have caught many people by surprise.

That hasn’t been the story coming out of Canberra in recent months. Treasurer Scott Morrison put on a sterling display of optimism during budget week, telling us that not only were lots of jobs being created, but the tax revenue flowing from those jobs would help bring the budget back to surplus.

Sadly, S&P has the more accurate picture. As noted on Wednesday, it sees our economy as “very high risk” due to “strong growth in private sector debt and residential property prices in the past four years”.

But the housing bubble is only half the story. Times have changed from the years when a large mortgage would quickly get easier to service as inflation eroded the real value of the debt.

Now, other forces of erosion are at work. Number-crunching last week’s jobs data from the Bureau of Statistics shows that it’s not debts that are eroding, but the number of hours of work available in the economy.

When the Treasurer quotes the jobs data, he tends to focus on the ‘seasonally adjusted’ unemployment rate, which fell from 5.8 to 5.7 per cent in April – the more reliable ‘trend’ figure remains stuck at 5.8 per cent.

But it’s what is happening behind those figures that is worrying.

First, there’s the ongoing trend towards part-time work. In the past year, the 49,300 full-time jobs created were easily eclipsed by 102,800 part-time jobs.

The growth rate for part-time jobs is three times that for full-time jobs, and if that trend continues over the next year, many heavily indebted households will start to reach breaking point.

The debt problem

Australia now has a middle strata of homeowners, between renters and those who’ve paid off their mortgages, who are carrying historically high levels of debt.

Not only are their debts not being significantly eroded by inflation, but the purchase price of homes in most cities continues to climb, loading up new generations of home buyers with even bigger debts.

That’s what S&P is concerned about. Mortgage holders are also struggling with two other trends – below-inflation wages growth, and the fall in hours worked revealed by the ABS last week.

While for an individual, having a part-time job is a lot better than none at all, for many families the problem of having one or even two breadwinners wanting more hours is growing.

This is what you need

Australia’s population is growing at a rapid annual rate of 1.4 per cent.

The workforce doesn’t grow quite that quickly due to the ageing population profile, but it’s not far behind – 1.36 per cent in the past year according to the ABS.

If workers’ hours had remained constant on average, the total hours worked would have risen by 22.5 million in the past year to reflect the expanding workforce.

What we saw last week was a fall of two million hours in the month of April, and growth over the year at half the level it should be – 10.4 million hours.

Those figures say a lot more about how the economy is progressing than simple ‘jobs’ figures, but even the job figures fell behind.

There have been 152,100 jobs created in the past year (to April), but the workforce has grown by 172,400 people in the same period. That is, more people than jobs available.

Household debt, meanwhile, continues its march higher. The average household debt is 190 per cent of disposable income, according to the RBA.

It’s important to remember, too, that most of that debt is concentrated in the one-third of households which have a mortgage.

That’s the slice of middle Australia for whom celebrations over a ‘fall in unemployment’ will make no sense.

RBA figures show that one third of mortgage-holders has less than a one-month buffer in the household finances before they fall into arrears.

That’s a risk for them, but also for the economy.

S&P is only telling us what the economists in the Department of Treasury already know, but the politicians aren’t keen to say.

Personal Insolvencies On The Rise

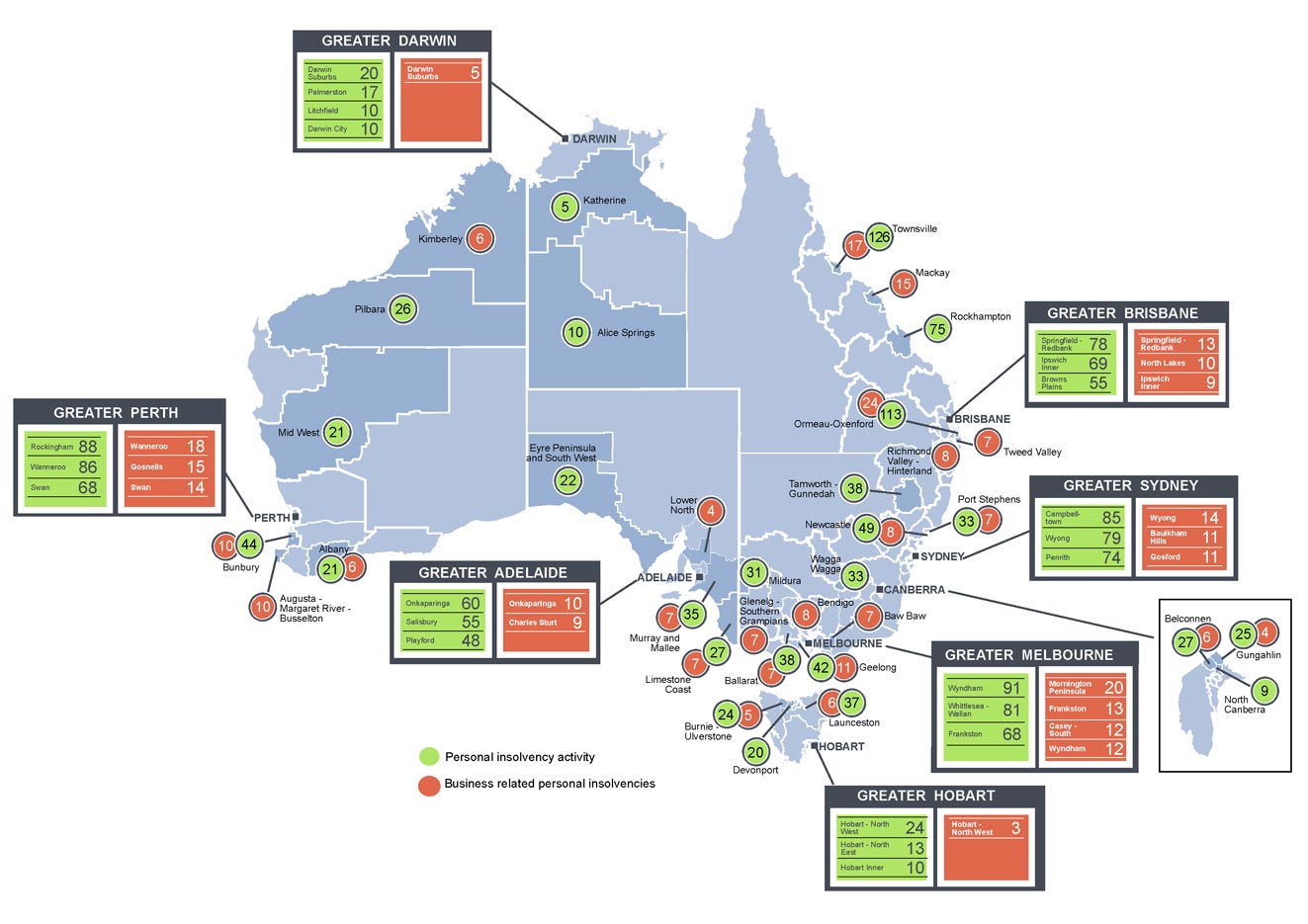

The Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) released regional personal insolvency statistics for the March quarter 2017. Looking across the regions, again we see signs of people in financial difficulty. This data will feed into our updated mortgage stress modelling to be published in early June.

New South Wales

New South Wales

- Greater Sydney

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 11.0%; the main contributor to the increase was Wyong

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 8.6%; the main contributors to the increase were Wyong and Penrith.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- Rest of NSW

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 1.9%; the main contributor to the increase was Lachlan Valley

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency fell 10.7%; the main contributor to the fall was Coffs Harbour.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

Australian Capital Territory

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 26.9%; the main contributor to the increase was Belconnen

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 84.6% (from 13 debtors to 24).

Victoria

- Greater Melbourne

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 13.4%; the main contributor to the increase was Whittlesea – Wallan

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose by 5.7%; the main contributor to the increase was Mornington Peninsula.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- Rest of Vic

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 10.8%; the main contributor to the increase was Glenelg – Southern Grampians

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 8.3%; the main contributor to the increase was Bendigo.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

Queensland

- Greater Brisbane

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 19.3%; the main contributor to the increase was Ipswich Inner

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 13.9%; the main contributor to the increase was Springfield – Redbank.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- Rest of Qld

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 9.4%; the main contributor to the increase was Caloundra

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency fell 2.1%; the main contributor to the fall was Rockhampton.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

South Australia

- Greater Adelaide

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 12.6%; the main contributor to the increase was Marion

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 9.8%.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- Rest of SA

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 51.0%; the main contributor to the increase was Murray and Mallee

- there were 25 debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency in the March quarter 2017, a rise from 12 in the December quarter 2016.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

Northern Territory

- The number of debtors rose 18.8% in Greater Darwin in the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016

- There were 18 debtors in rest of NT in the March quarter 2017, a fall from 20 in the December quarter 2016

- There were 13 debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency in Northern Territory, a fall from 16 in the December quarter 2016.

Western Australia

- Greater Perth

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 11.6%; the main contributor to the increase was Cockburn

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency was unchanged at 155 debtors.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- Rest of WA

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors rose 5.3%; the main contributor to the increase was Albany

- the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency rose 9.1%; the main contributor to the increase was Bunbury.

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

Tasmania

- In the March quarter 2017 compared to the December quarter 2016:

- the number of debtors who entered a personal insolvency in Greater Hobart fell 7.2%; the main contributor to the fall was Brighton

- the number of debtors rose 35.5% in rest of Tas; the main contributor to the rise was Launceston

the number of debtors who entered a business related personal insolvency in Tasmania was unchanged at 28 debtors.

Avocados and housing affordability? It’s a green herring

Avocados are in the news again, which must mean housing affordability is too. This time it was wunderkind property developer Tim Gurner who told 60 Minutes that millennials “buying smashed avocado for 19 bucks and … coffees at $4 each” shouldn’t be complaining about the difficulty of getting into the property market.

But blaming young people for eating pricey avo brunch doesn’t shed any light on housing affordability. It’s just a green herring.

Mr Gurner is probably right that a lot of young people are happy to live a life of brunch and overseas travel. But these are unlikely to be the same Australians who feel locked out of the housing market. They either can afford to buy a home, or are happy renting or living with their parents while they enjoy their 20s. And good on them.

The real problem is that the real estate market roundly cheered for decades has turned out to be a Ponzi scheme of sorts. Rapidly and consistently rising real estate values enhanced the wealth of many Australians, but the rest have been stranded.

Rising prices have been a staple barbecue and dinner party topic of conversation since the heady 1980s. It was a decade of financial deregulation, easy access to home lending and a bullish sense of prosperity. Economic reform had transformed the ‘Great Australian Dream’ into the ‘Great Australian Wealth Machine’.

A report by property analyst CoreLogic shows that in the five years to 2016 the proportion of household income required for a 20 per cent deposit on a home climbed from 85.9 to 138.9 per cent. This at a time of static wage growth, adding to the difficulty of raising a home deposit. In the five years to 2016, national dwelling prices rose by 19 per cent while household incomes rose by just 9.2 per cent.

Australia remains a nation of homeowners, but the Great Australian Dream is under pressure. Nationally, according to the Melbourne Institute, 68.8 per cent of households were owner-occupied in 2001; by 2014 this had fallen to 64.9 per cent. The impact of investors on the housing market is also clear. According to the Bureau of Statistics, at the close of 2016, investors comprised 47 per cent of national mortgage demand – 55 per cent in NSW.

For those who do feel unable to realise their dream of home ownership, avocados aren’t the problem. They’re locked out because of inflated property values, poor wages growth, the impact on supply of a rapidly rising population, and people like Tim Gurner whose wealth depends on stoking the market.

Sadly, it’s difficult to assume there is a ready solution out there just waiting to be discovered.

Public policy does have a role to play in addressing housing affordability, but how far can policy go in solving a problem which at its root is down to market forces?

Treasurer Scott Morrison was irresponsible when he flagged that housing affordability was going to be the centrepiece of his budget. Once again, the Turnbull government set expectations it was unable to meet.

The Budget’s ‘ta-da’ contribution to easing the burden for first homebuyers was the “first home super saver scheme” which will allow first-home buyers to make voluntary contributions of up to $30,000 to their superannuation which will be made available for a home deposit at concessional tax rates.

University of NSW economics professor Richard Holden says the measure will do “absolutely nothing to help first home owners”, arguing, as many others have, that the subsidy will actually force home prices higher.

“It’s bad economics, somewhat costly and a cruel hoax on prospective home buyers who are struggling with an out-of-control housing market,” he wrote in The Conversation.

The key to addressing housing affordability is not policy sophistry whose only purpose is to give the impression of action. A more nuanced understanding of Australia’s housing market, in the context of a rapidly changing economy, is required before meaningful policy settings can be made. Housing affordability also needs to be understood in the context of a rapidly growing population.

We need fewer policy stunts from the government and a more considered vision for Australia in the 21st century. It may well be time for the Great Australian Dream to be updated. The Great Australian Dream 2.0.

Economists are trying to out why incomes aren’t rising — but workers have a good hunch

Economists are often wringing their hands over why, despite a continuous eight-year economic recovery, US workers’ wages remain largely stagnant, extending a trend that began some three decades ago.

Yet anyone who has applied for a job in the last couple of years knows that, while the US unemployment rate is historically low at 4.4%, the labour market isn’t exactly bustling.

Companies have become a lot more reticent about making new investments in the wake of the Great Recession and during the weak economic recovery that has followed it. That includes investing in people, and the hiring process has become slower and more onerous.

It also means wage increases have become even harder to come by.

The recession caused lasting damage to the job market which still resonates to this day. Steven Partridge, vice president for workforce development at Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA), says the crisis created what he calls “degree inflation” in job requirements — a trend correlated with stagnant and sometimes falling incomes as workers lost their jobs and considered themselves lucky to take lower-paying ones.

In other words, because applicants were so desperate and the pool was so wide, the bar for hiring became unrealistically, and often unnecessarily high. The trend has abated, but not fully receded.

“The downturn made everyone push up their education requirements,” Partridge told Business Insider.

Several job market indicators point to underlying weakness — high levels of long-term joblessness, low labour force participation and, yes, a distinct lack of wage growth.

Albert Edwards, market strategist at Societe Generale, deserves credit for doing something that’s rather rare on Wall Street — admitting he was wrong, specifically about the prospect of imminent wage increases.

“Talking about wrong, I have to put my hands up. I have been expecting US wage inflation to roar ahead over the past three months to well above 3%, yet every data release has surprised on the downside,” he wrote in a note to clients.

“Wage inflation, as measured by average hourly earnings, has actually leveled off at close to 2-1⁄2% while wage inflation for ‘the workers’ is actually slowing (see chart below)! Strictly speaking, the workers are defined (by the BLS) as those who are not primarily employed to direct, supervise, or plan the work of others. Hey, thats me!”

Societe Generale

Fed officials have also struggled to understand the absence of wage increases. In a recent research brief from the San Francisco Fed, staff economist Mary Daly and co-authors reflect on what they see as a surprising trend.

“Standard economic theory tells us that wage growth and unemployment are intimately linked. Wage growth slows when the unemployment rate rises and increases when the unemployment rate falls,” they write. “The experience since the Great Recession has been very different.”

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

“This slow wage growth likely reflects recent cyclical and secular shifts in the composition rather than a weak labour market. In particular, while higher-wage baby boomers have been retiring, lower-wage workers sidelined during the recession have been taking new full-time jobs,” they said. “Together these two changes have held down measures of wage growth.”

Their explanation provides little comfort in the face of the depressed labour market many Americans still face, especially lower-income and minority families.

The Fed authors also suggest a factor in low income growth that might ring true to those families: “As long as employers can keep their wage bills low by replacing or expanding staff with lower-paid workers, labour cost pressures for higher price inflation could remain muted for some time.”

As suggested in that last excerpt, labour’s bargaining power vis-a-vis employers is probably at least as important as unfavorable demographics in explaining slow wage growth. It will take a substantially stronger economy to tilt that balance back in workers’ favour.

The Property Imperative Weekly – May 20th 2017

The latest edition of our weekly roundup of property, finance and economics review is available. We discuss the latest economic news, recent developments in the bank tax debate and the latest mortgage pricing and volume data.

Watch the video or read the transcript.

This week, the latest updates from the ABS showed that the trend unemployment rate stuck at 5.8%, thanks to a large rise in part-time employment. In fact, employment was up by a very strong 37,400 in April after increasing by a massive 60,000 in March but the total hours worked was reported to have fallen by 0.3% in April and was down by 0.1% over the past two months. This may be because of changes in the ABS sampling. Many commentators suggest the true position in worse, but we do know that unemployment was above 7% in South Australia, and the number of older people seeking work also rose.

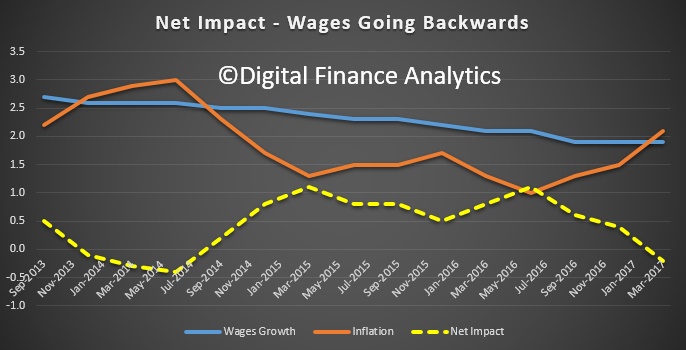

The latest wages data, showed that the seasonally adjusted Wage Price Index rose 0.5 per cent in the March quarter 2017 and 1.9 per cent over the year, according to ABS figures. This makes a bit of a joke of the strong wages growth rates predicated in the recent budget.

The seasonally adjusted, Wage Price Index has recorded quarterly wages growth in the range of 0.4 to 0.6 per cent for the last 12 quarters. However, private sector wages rose 1.8 per cent whilst public sector wages grew 2.4 per cent, so public servants are doing better than the rest of the population.

The pincer movement of higher inflation and lower wage growth now means that average wages are falling in real terms, especially for employees in the private sector. Not good for those with mortgages as rates rise flow though. This aligns with our Mortgage Stress data.

There was further heated debate about the Bank levy, with the Treasurer saying on ABC Insiders that the impost was a permanent measure and linked to the strong profits and competitive advantage the big four have thanks to the “too-big-to-fail” implicit guarantee from the government. He again said the costs of the tax should not be passed on to customers.

On the other hand, the banks put their own slant on the issue, saying that the costs would be passed on, and the levy was bad policy. Ex Treasury Boss Ken Henry, now the Chairman of NAB, suggested there should be an inquiry into the proposed tax and said it looked like something from the eighties, before all the free market reform.

The banks made submissions to the Treasury complaining about the short timeframes, and seeking a delay in implementation. ANZ suggested a delay till September 2017 to allow sufficient time for design of the legislation and also recommended the tax should be applied to the domestic liabilities of all banks operating in Australia with global liabilities above $100 billion. They concluded “There is no ‘magic pudding’. The cost of any new tax is ultimately borne by shareholders, borrowers, depositors, and employees”.

But the real debate should be framed by the excess profits the big banks make, and the unequal position the big four have thanks to the implicit government guarantee, meaning they can out compete regional and smaller lenders. In fact, the value of this subsidy is significantly higher than the 6 basis points being imposed. These are the very high stakes in play, and the outcome will significantly impact the future shape of banking in Australia. In fact, you could argue the big four receive the largest subsidies of any industry in the country – way more than, for example, the entire car industry.

In addition, the Australian Bankers Association is caught trying to represent the interest of the big four, and other regional players, including some who have supported the tax on the basis of it helping to level the competitive landscape. The ABA issued a statement to say there was no division, but there clearly is. Not pretty. Some have suggested the smaller players should create their own separate lobby group.

The latest lending data from the ABS showed that the mix of lending is still too biased towards unproductive home lending, at the expense of lending for commercial purposes. Overall trend finance flow in trend terms rose 1.3% to $70 billion, up $691 million. The total value of owner occupied housing commitments excluding alterations and additions rose 0.1% in trend terms, to $20.1 billion, up $26 million. Within the fixed commercial lending category, lending for investment housing fell 0.3%, down $44 million to $13.2 billion, whilst lending for other commercial purposes fell 2%, down $416 million to $20.3 billion. 39% of fixed commercial lending was for investment housing and this continues to climb. Most of the investment in housing was in Sydney and Melbourne.

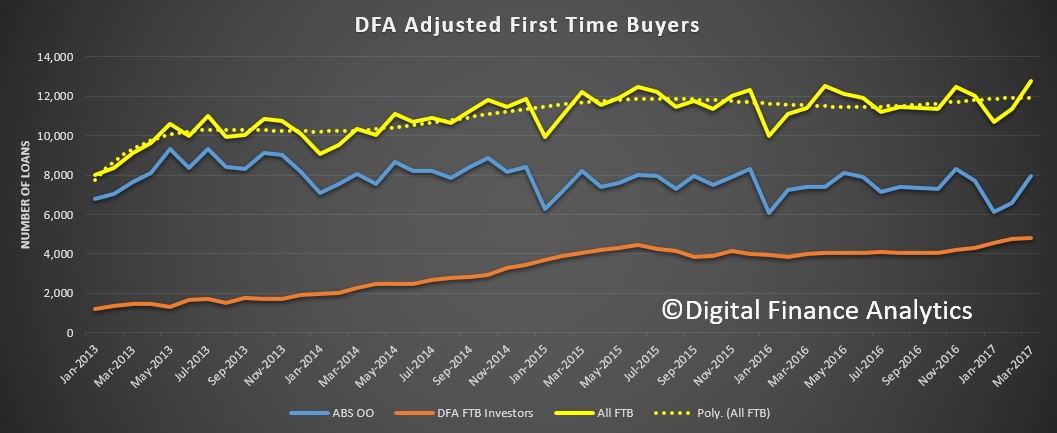

The more detailed housing finance data showed that the number of owner occupied first time buyers rose in March by 20.5% to 7,946 in original terms, a rise of 1,350. In original terms, the number of first home buyer commitments as a percentage of total owner occupied housing finance commitments rose to 13.6% in March 2017 from 13.3% in February 2017.

The DFA surveys saw a small rise in first time buyers going to the investment sector for their first property purchase. Total first time buyers were up 12.3% to 12,756, still well below their peak from 2011 when they comprised more than 30% of all transactions. Many are being priced out or cannot get finance.

Lenders continued to tighten their underwriting standards for interest only loans, with CBA, for example, ending discounts, fee rebates and dropping the LVR to 80%, having in recent months imposed no less than three rate rises on the sector. ANZ tightened their lending parameters too, with the maximum interest only period reduced from 10 years to five years, tightening LVRs and imposing other restrictions.

Overall we think the supply of investor loans will reduce, and that smaller lenders and non-banks will not be able to meet the gap, so we are expecting loan growth to slow further, and the price of loans to rise again.

We also saw auction clearances stronger last weekend, so this confirms our survey results, that households still have an appetite for property, despite tighter lending conditions. Recent stock market falls and greater market volatility will play into the mix now, so we think there will be a tussle between demand for property, especially for investment purposes and supply of finance.

Brokers may well get caught in the cross-fire, and the recent UBS report suggesting that brokers are over-paid for what they do, will not help. Others have argued UBS got their sums wrong, and denounced the report as “ridiculous”.

It is still too soon to know whether home price growth is really likely to turn, but the strong demand still evident in Sydney and Melbourne suggests momentum will continue for as long as credit is available at a reasonable price. So I would not write off the market yet!

And that’s it from the Property Imperative Weekly this time. Check back for next week’s summary.

The human face of Australia’s housing crisis

Chris Radford and Michelle Apostolopoulos are high school sweethearts. They met and fell in love at Northcote public school, which sits on the same main road that runs near both their parents’ fully paid off houses.

They both rent in Melbourne and are fast approaching the age their parents married, bought houses and started families. Repeating that feat in today’s market seems impossible.

Chris, 24, has spent the last six years of his life stacking shelves in a trendy inner-city supermarket, so he knows the price of avocados – that symbol of millennial decadence that is supposedly holding him back from property ownership.

“Four bucks, five bucks each. Yeah, I know how much they cost,” he says. “I don’t eat a lot of avocado to begin with.”

The couple, who plan to marry soon, are exactly who Treasurer Scott Morrison’s latest federal budget was supposed to help: hard-working, hard-saving Australians who want nothing more than a modest home to call their own.

Unlike their parents’ generation, the ‘Australian Dream’ seems to be getting further out of reach, what with rising prices, penalty rate cuts and record-low wage growth.

Chris pays $110 a week for a room in a house he shares with two friends in the Melbourne suburb of Moonee Ponds. When it rains, water drips through the ceiling into a strategically placed pot.

The house will soon be knocked down for apartments, so the landlord has given up on the place.

When his parents bought their house in Thornbury for $80,000 back in 1991 it was not much of a stretch for two people in their mid-20s. It is now worth at least $1 million, probably more.

Because of this enormous increase in value, buying even a more modest house today requires vastly more effort. Chris and Michelle, 23, estimate that a median-priced Melbourne home will require them to save a 20 per cent deposit of $150,000.

Even if they were to save every dollar they earn, it would still take them years to build that much – and that’s without taking price growth into account.

“It’s so unfair, two people should be able to save enough in a few years for a house!” Michelle says.

“Even if we saved hard I know we wouldn’t be able to afford within 32 kilometres of here.”

Part of the reason that saving is so hard for the couple is the new round of attacks on their pay.

Chris has worked his supermarket job all through high school and now into university. He works Sundays and has for years. He also works unpaid at an internship as part of his university degree, which requires him to work full-time on top of his part-time work.

This leaves him relying heavily on weekend penalty rates — which he’ll lose come July 1 because of a recent decision by the Fair Work Commission.

“If I didn’t have to work on Sunday, I wouldn’t,” he says.

Michelle, too, regularly works weekends. But because she works for one of Australia’s two main supermarkets, she’ll be lucky enough to keep her penalty rates.

“People who work weekends miss out on seeing family and friends,” she says.

“You deserve [penalty rates], you’ve busted your arse all weekend.”

They’re both disappointed the government didn’t do more in the budget to make things easier for low-paid workers and aspiring property buyers like themselves. Treasurer Morrison’s plan to allow first home buyers to tip up to $30,000 into their superannuation doesn’t excite them.

“When you really look at the details it starts looking practically impossible,” Michelle says.

“The government isn’t doing anything to make it easier to buy a house.”

To make matters even worse, with the university debt repayment threshold dropping, Chris and Michelle will both have to pay back more to the government each year.

“A lot of people think you’re not working hard enough if you can’t save a deposit. They just pick on young people because we can’t do anything about it,” she says.

“What are you supposed to do? Store everything in a cardboard box, then live in the cardboard box too?”

The Growing Skill Divide in the U.S. Labor Market

The St. Louis Fed On The Economy Blog has highlighted a polarization in the labor market, between skilled employees capable of performing the challenging tasks in the cognitive nonroutine occupations and entry-level employees that are physically strong enough to perform the manual nonroutine tasks.

Over the past several decades, the skill composition of the U.S. labor market has shifted. Employers are hiring more workers to perform nonroutine types of tasks (such as managerial work, professional services and personal care) and fewer workers for routine operations (such as construction and manufacturing). This shift in the type of skills in demand is referred to as job polarization.

One way to see evidence of job polarization is to look at employment growth in certain occupational classifications. The figure below divides occupational employment growth into four groups:

- Cognitive Nonroutine: managers, computer scientists, architects, artists, etc.

- Manual Nonroutine: food preparation, personal care, retail, etc.

- Cognitive Routine: office and administrative, sales, etc.

- Manual Routine: construction, manufacturing, production, etc.

The black lines represent the average growth rate across all occupations within a group, while the bars represent the growth rate in that particular occupation.

The fastest growing occupational groups are cognitive nonroutine and manual nonroutine, both growing about 2 percent every year on average since the 1980s. Cognitive routine and manual routine occupations are growing significantly slower, less than 1 percent on average (or shrinking, in the case of production occupations).

Physical Demands of Work

One of the implications of job polarization is a shift in the type of work required to be performed by the average employee. A new survey from the Bureau of Labor Statistics—the Occupational Requirements Survey—gathers data on the type of work performed in each occupation.

The figure below looks at two physical task requirements:

- The percentage of hours in an eight-hour day spent standing or walking

- The percentage of workers required to perform pushing or pulling tasks with one or both hands

The most physically demanding occupational groups are manual nonroutine and manual routine. In both of these groups, on average more than half of the employees are required to push or pull with their hands, and over half of their day is spend standing or walking.

In contrast, less than 35 percent of workers in the cognitive nonroutine and cognitive routine groups push or pull with their hands. These groups also spend much less time standing/walking.

Decision-Making at Work

The last figure looks at two cognitive task requirements:

- The percentage of workers where decision-making in uncertain situations or conflict is required

- The percentage of workers whose supervision is based on broad objectives and review of results

These requirements are easier to think about in terms of a spectrum. For example, occupations that require less cognitive activity either lack decision-making entirely or involve straightforward decisions from a predetermined set of choices.

Similarly, occupations with a greater cognitive requirement usually involve broad objectives with end-result review only, while more manual occupations require detailed instructions and frequent interactions with supervision (for example, a consultant’s quarterly performance review versus daily quality control checks in a factory).

By a large margin, the cognitive nonroutine occupations involve more challenging decision-making and less frequent interactions with supervision. The other occupational groups all have fewer than 10 percent of employees engaging in these types of cognitive tasks.

Job Growth According to Skill Requirements

The figures above show a stark contrast between the skill requirements in the two occupational groups growing the fastest. The cognitive nonroutine group requires complex decision-making, independent working conditions and less physical effort, while the manual nonroutine group still requires quite a bit of physical effort and does not involve a high level of cognitive tasks.