Almost nothing is to be seen of Australia’s housing crisis in the latest inflation figures.

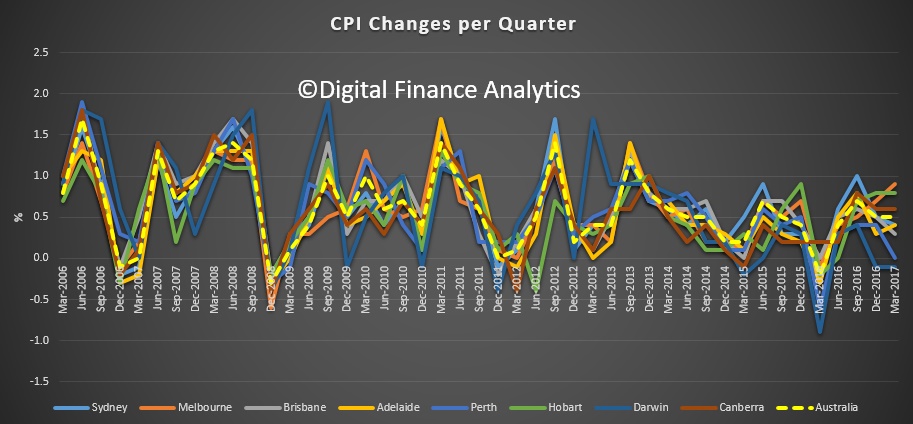

Wednesday’s Consumer Price Index (CPI) from the Australian Bureau of Statistics showed just a 0.5 per cent increase in inflation this quarter, up 2.1 per cent over the past 12 months.

Over the same period, house prices grew 1.4 per cent, and by 75 per cent over the past five years.

The biggest increases in the CPI were in fuel, healthcare, power and, yes, housing.

However, as pointed out recently by Commonwealth Bank senior economist Gareth Aird, this ‘housing’ figure, which accounts for 22 per cent of the CPI calculation, does not truly reflect the struggle of many Australians to get onto the property ladder.

“The CPI is a poor barometer of changes in the cost of living for people who don’t own a dwelling and aspire to purchase one,” Mr Aird wrote.

That’s because the CPI measure of ‘housing’ only counts rents, utilities and the cost of building a new dwelling. It doesn’t include the cost of the land the dwelling sits on. And it doesn’t include the interest costs of repaying a mortgage.

If the full cost of housing was factored in, Mr Aird estimated it would add roughly 55 percentage points to headline inflation.

As mentioned above, the CPI ‘housing’ measure also doesn’t include interest charges. It used to, but they were removed in 1998 after lobbying from the Reserve Bank, which argued that rising mortgage interest rates would push up inflation, thereby requiring official cash rate rises, which would then push mortgage rates even higher, in a vicious loop.

The RBA said then that “excluding interest charges would in no way distort the outcome over the long run”.

Australia Institute senior research fellow David Richardson said if the CPI were to include land prices, the inflation rate would be pulled too hard by almost out of control house prices.

“Imagine if things went up 15 per cent a year in price,” Mr Richardson told The New Daily.

“Lots of contracts in Australia are indexed against the CPI. If they’re sort of fiddled then you’re talking billions and billions in consequences.”

Marcel van Kints, program manager with the Prices Branch of the ABS Macroeconomic Statistics Division, told The New Daily: “The ABS CPI aligns with international standards, an international respected measure of inflation.”

The ABS also published a FAQ with Wednesday’s release in which they pointed to their reasoning behind the exclusion of land from the CPI.

They said that housing is included in the Selected Living Cost Indexes, which are “particularly suited to assessing whether or not the disposable incomes of households have kept pace with price changes”.

Inflation outpaces wages

All of this is seeing many Australians left behind as both housing and the prices of popular consumer goods rise while wages stagnate.

Over the past 12 months, the CPI rose 2.1 per cent while wages grew by only 1.9 per cent, according to the latest ABS data.

The Australia Institute’s David Richardson said this is leaving many Australians worse off.

“I suspect that as professionals and skilled white collar workers, we’re all in the same boat,” he said.

“What we’re seeing now is a symptom of structural change that’s been creeping up on us for a long time.”