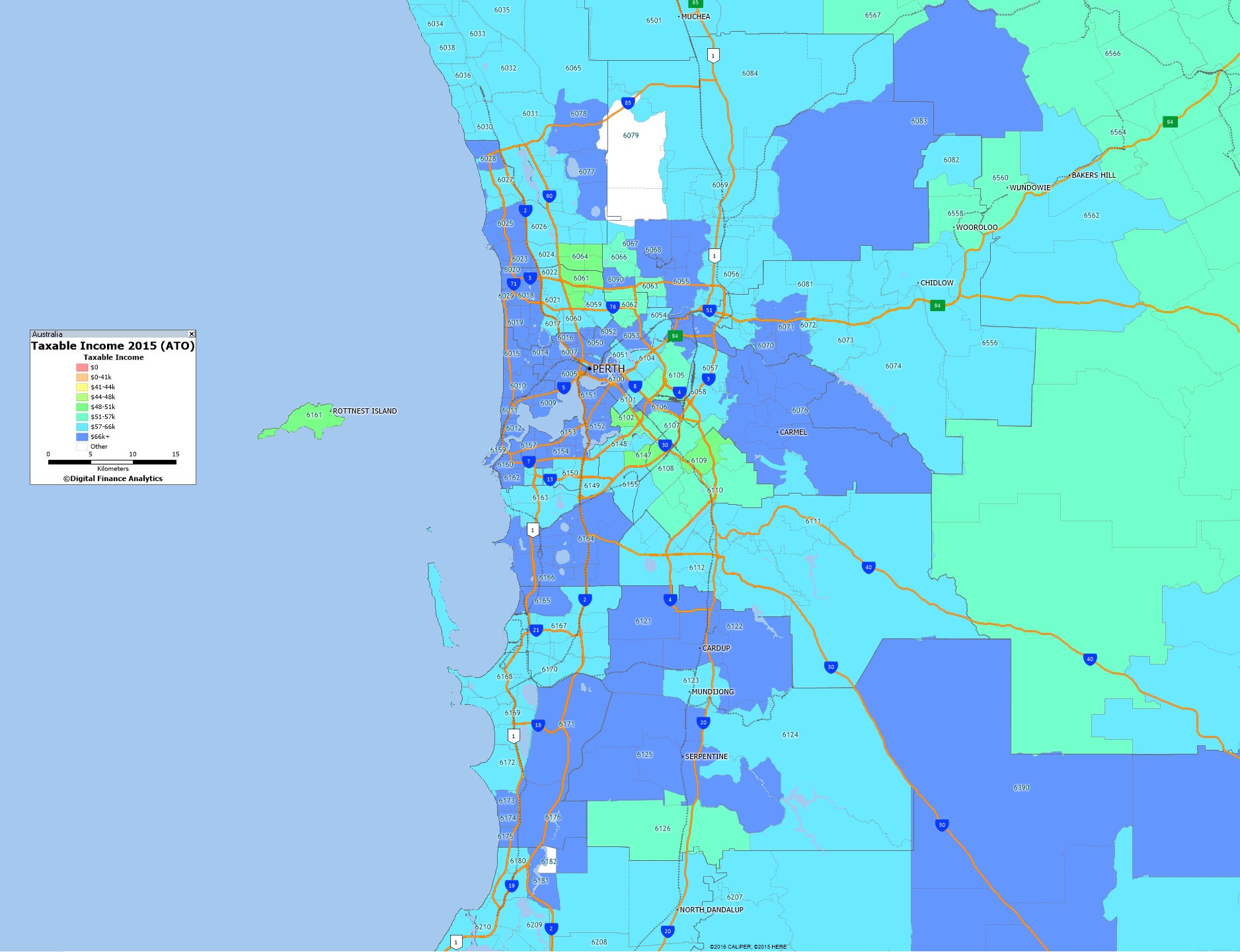

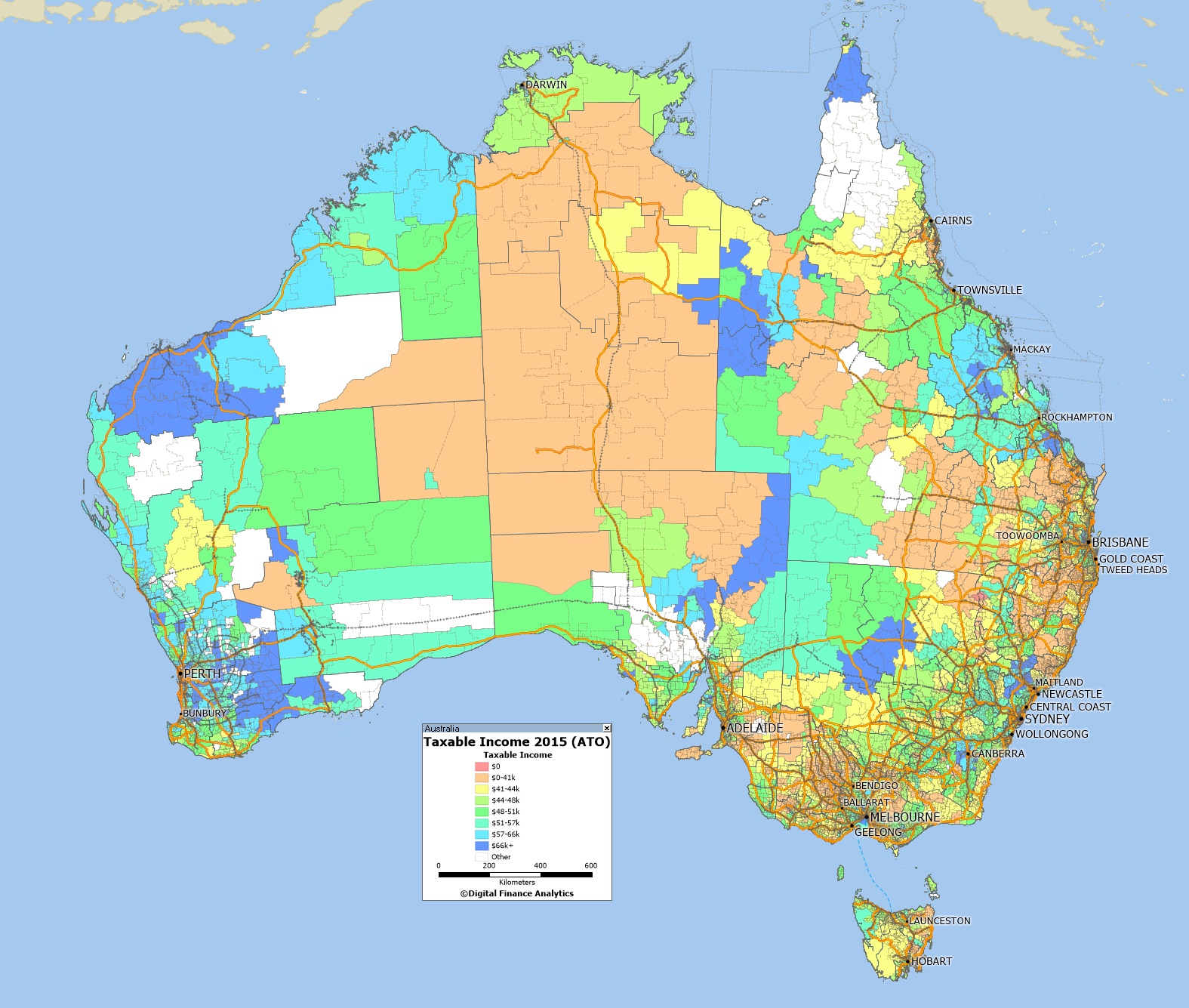

We continue our series on the latest ATO data with a look at Greater Perth, using the recently released 2015 taxable income data from the ATO, as a drill down on the all Australia data we previously posted. Blue shows the higher taxable income areas.

Category: Social Trends

Taxable Income Mapping Greater Melbourne 2015

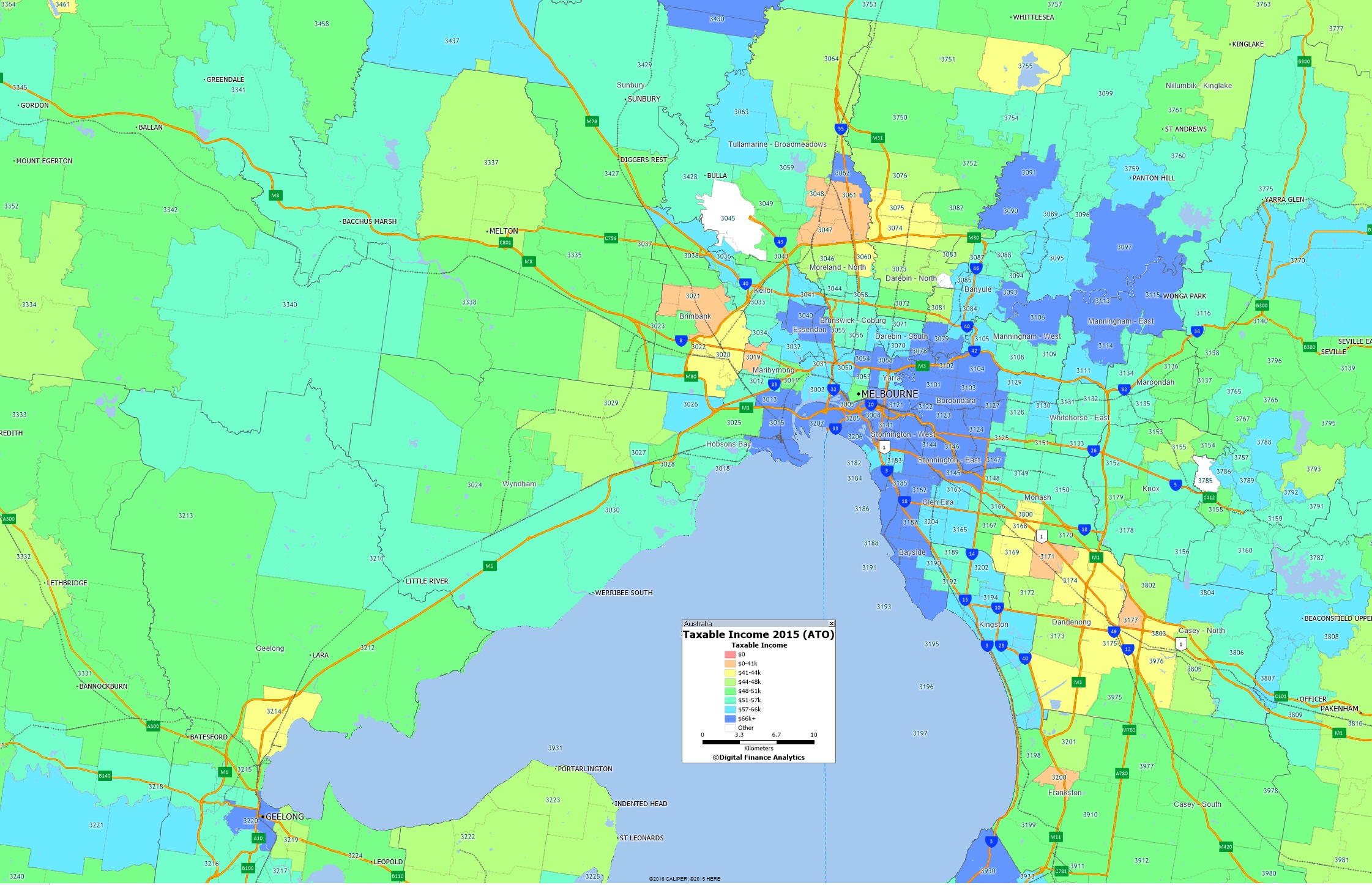

We continue our series on the latest ATO data with a look at Greater Melbourne, using the recently released 2015 taxable income data from the ATO, as a drill down on the all Australia data we previously posted. Blue shows the higher taxable income areas.

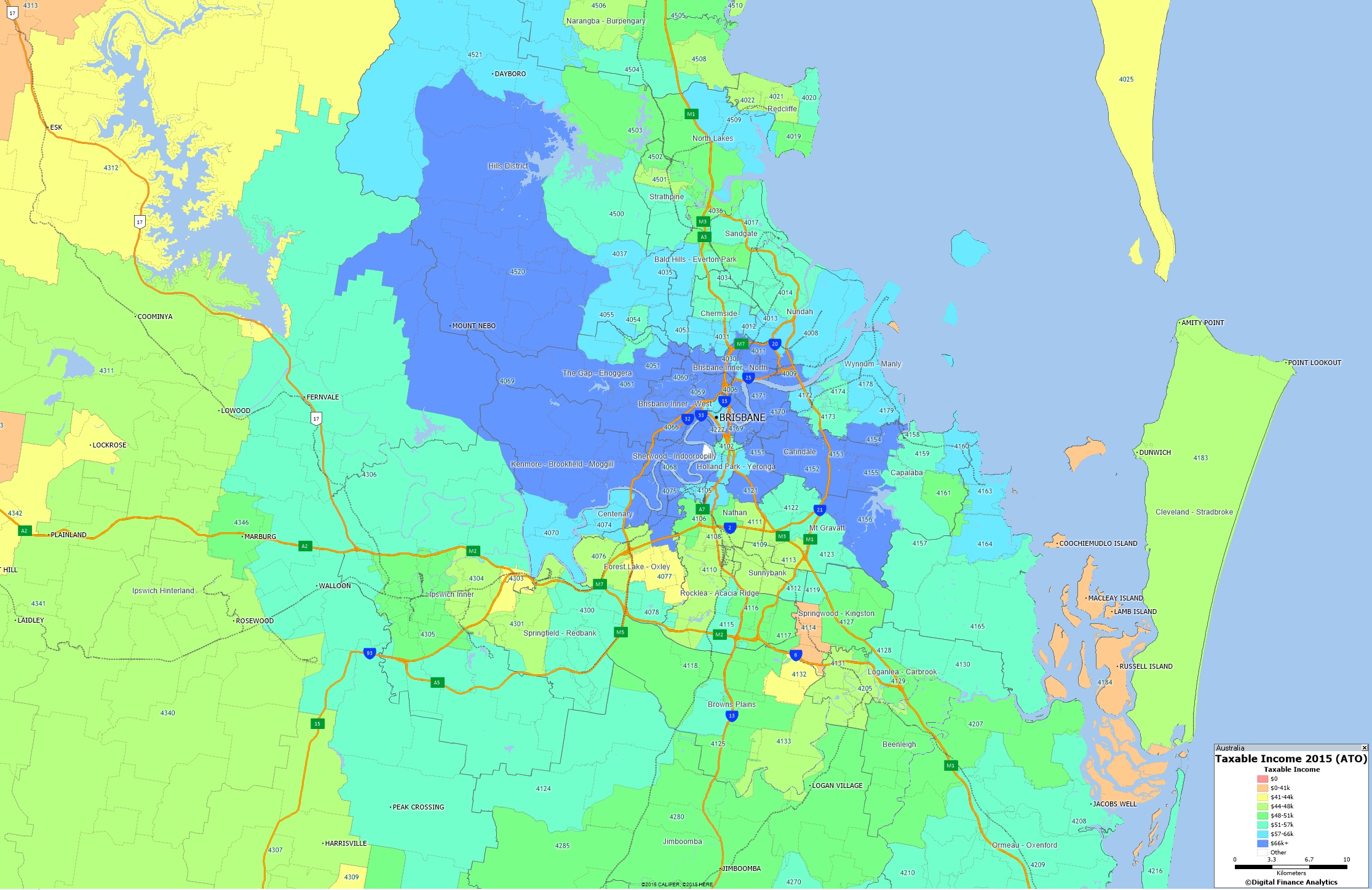

Taxable Income Mapping Greater Brisbane 2015

We continue our series on the latest ATO data with a look at Greater Brisbane, using the recently released 2015 taxable income data from the ATO, as a drill down on the all Australia data we previously posted. Blue shows the higher taxable income areas.

ATO data shows inequality is in everything from super to the property market

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) has released data for 2014-15 that paints a picture of how much Australians earn and what they claim in tax concessions. We asked our tax experts to tell us what the data says to them.

John Daley and Danielle Wood, The Grattan Institute

The latest data from the ATO is consistent with what we’ve seen in the past. It shows that people with high-income occupations – doctors, lawyers, and others – are more likely to use negative gearing than the nurses and teachers on whom Treasurer Scott Morrison focuses when he tries to justify retaining negative gearing. It also shows that negative gearing is typically worth four to five times more for doctors and lawyers than nurses and teachers.

Author provided

The tax data shows that with falling interest rates, fewer landlords are negatively geared, and the average loss is also falling. Overall the investor property market seems to be concentrating a little, with slightly fewer landlords but more investment properties per landlord.

Author provided

Negative gearing has lots of problems. It costs the budget a lot of money, distorts investment decisions, increases house prices, and reduces home ownership, while doing little to increase supply.

The government claims it should nevertheless be retained because it’s primarily an investment strategy for “mums and dads”. But the detailed tax data from previous years shows that about two-thirds of the benefit goes to the one-fifth of taxpayers with the highest income before the negative gearing deduction.

We will have to wait until later this month for the release of more detailed data to check that this is still true.

Professor Fabrizio Carmignai, Griffith Business School

This data delivers a simple, probably not unexpected, but still concerning message: inequality in Australia is increasing.

We can see this in terms of the growing gap between the richest and the poorest suburbs, as well as an increase in dispersion across all suburbs.

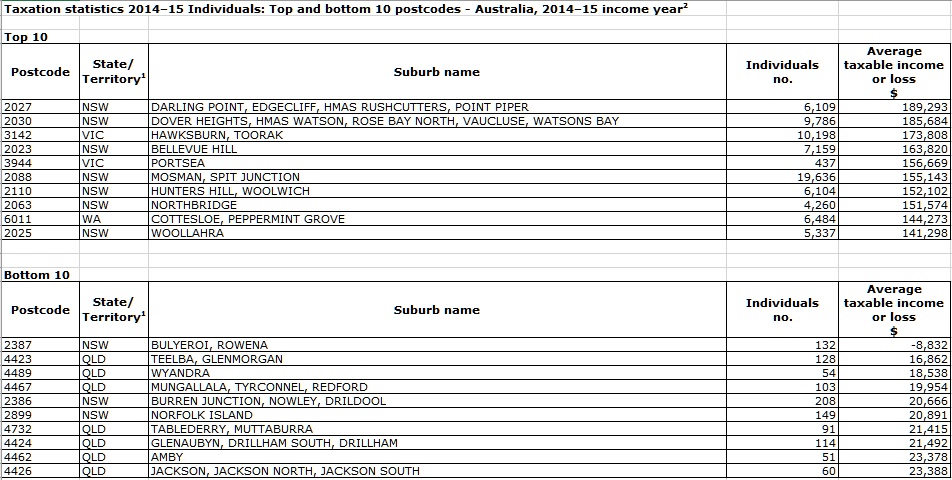

For example, the data published yesterday indicates that average taxable income in the ten poorest postcodes was only 11% of the average taxable income in the ten richest postcodes. A decade ago, in 2004-05, income in the ten poorest postcodes was 21% of income in the richest postcodes.

In fact, while the average income at the top of the distribution has grown by 30% in a decade, average income at the bottom has actually declined by 33%. If we look at the overall dispersion of incomes by postcode, we can see that this has gone up by approximately 25% in ten years.

Whichever way we look at it, the conclusion is that there is more income inequality today than ten years ago.

The other interesting aspect to the data is that the richest postcodes today are more or less the same as ten years ago. Indeed, seven of the top ten postcodes in 2014-15 were already in the top ten in 2004-05. But this same trend is not observed at the bottom: none of the ten poorest postcodes today were in bottom ten in 2004-05.

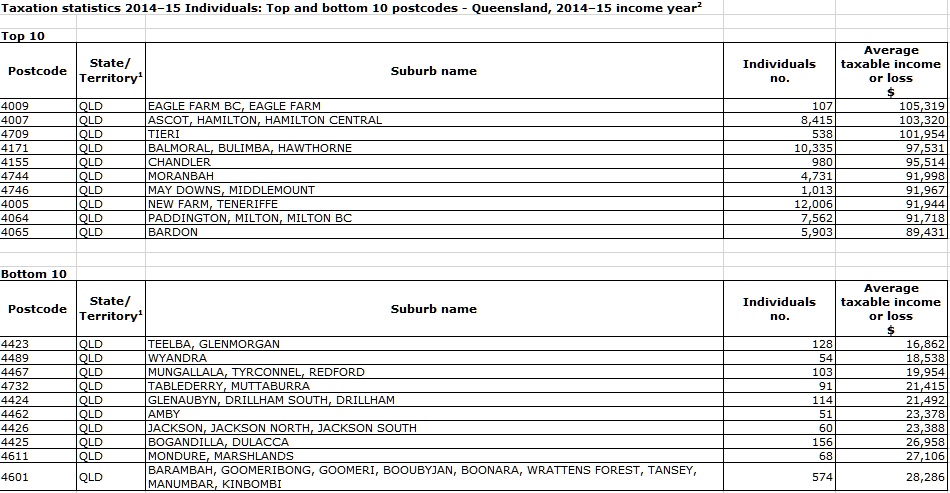

And there is some bad news for Queensland in particular: the proportion of the state’s postcodes in the bottom ten has increased considerably, from three out of ten in 2004-05 to seven out of ten in the latest data. This data might be indicative of a growing poverty problem in this state.

Associate Professor Helen Hodgson, Curtin Law School

The ATO’s data clearly shows that the self-managed superannuation fund (SMSF) sector is not only continuing to grow, but is used primarily by people with the ability to make higher contributions; either high income earners or those late in their careers.

Members of self-managed superannuation funds made significantly higher contributions and have higher balances than members of Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority (APRA) regulated funds.

The data shows that on an individual basis, the median contribution to a SMSF was A$20,000. Meanwhile, members of APRA funds made median contributions of A$4,507.

Similarly, the super balances of members of SMSFs are significantly higher than APRA funds. SMSF members have median balances of A$289,483, compared to just A$32,734 for those in APRA regulated funds. The data also shows that a small proportion of people have very high balances, which is reflected in the difference between the median and mean balances in the statistics.

Two of the forthcoming changes to superannuation will limit contributions and impose a cap on balances, which should impact higher earners. Most people who made contributions in excess of A$25,000 are over 45 and earned more than A$180,000.

But the changes to the superannuation system will not take effect until July 2017, so it is too soon to know how that will impact superannuation funds. However the division between the self-managed and APRA regulated funds is clear.

Authors:Jenni Henderson, Editor, Business and Economy, The Conversation; Josh Nicholas, Deputy Editor Business & Economy, The Conversation; Interviewed: Danielle Wood, Fellow, Australian Perspectives, Grattan Institute; Fabrizio Carmignani, Professor, Griffith Business School, Griffith University; Helen Hodgson, Associate Professor, Curtin Law School and Curtin Business School, Curtin University; John Daley, Chief Executive Officer, Grattan Institute.

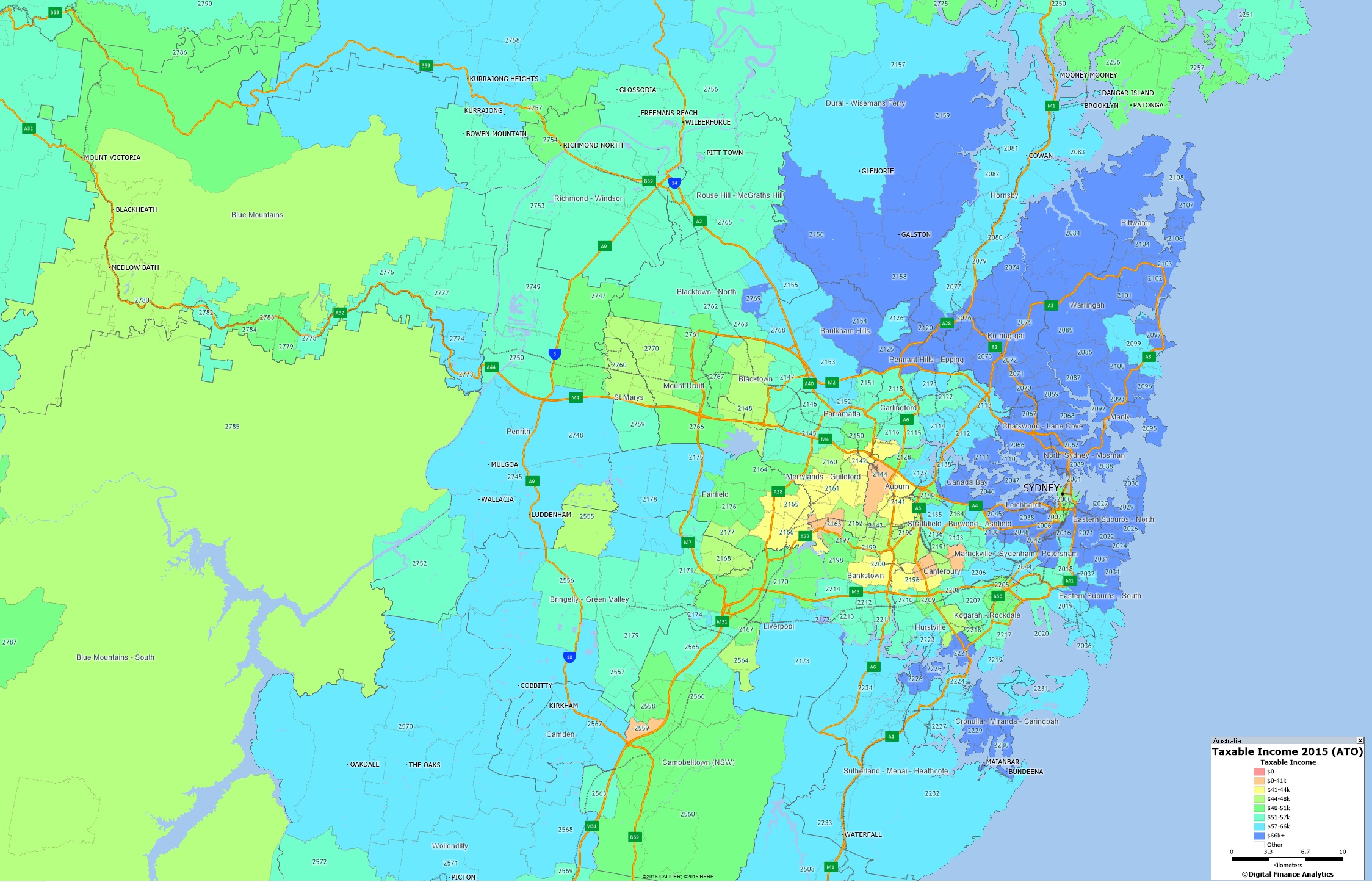

Taxable Income Mapping Greater Sydney 2015

Here is the geomap for Greater Sydney, using the recently released 2015 taxable income data from the ATO, as a drill down on the all Australia data we previously posted. Blue shows the higher taxable income areas.

Taxable Income Mapping Australia 2015

Using data from the latest ATO release from 2015, we can map average taxable incomes to post codes. Of course taxable incomes are the residual amounts the tax authorities get their hands on after tax management strategies (such as allowances, expenses, trusts, negative gearing, income sharing and the like) so they do not tell the full story. Nevertheless the results are interesting.

The blue areas show the zones of highest taxable income. Here are the top and bottom postcodes from the list, Australian wide.

The blue areas show the zones of highest taxable income. Here are the top and bottom postcodes from the list, Australian wide.

In coming days we will drill into the various states, again with interesting results.

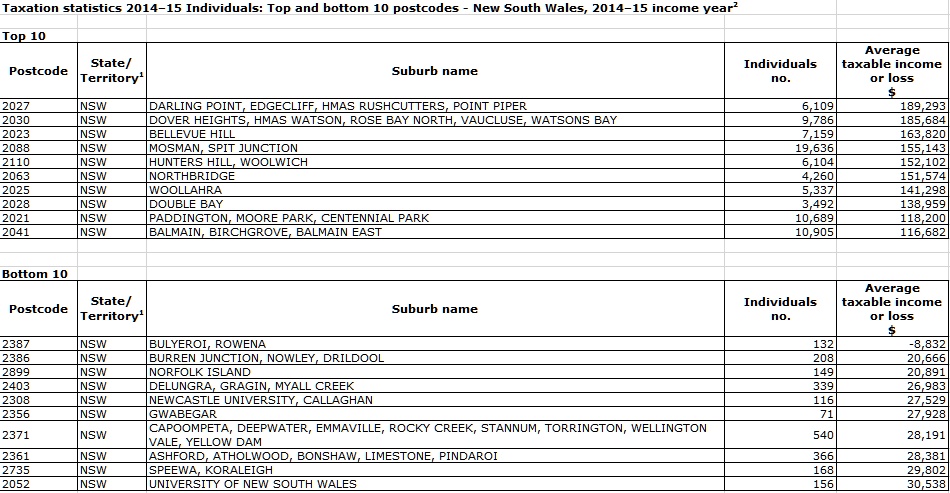

ATO reveals Australia’s richest and poorest postcodes

Sydney’s eastern suburbs have retained their title as the home of Australia’s richest residents.

That’s the word from the Australian Taxation Office, which names postcode 2027 as the single largest concentration of blue-chip earners in the nation, with an average individual income of $189,293, based on newly released tax return statistics from 2014-15.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise. The plush pocket of harbourside high-earners includes Point Piper, where Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull makes his home in a waterfront mansion estimated by Domain.com.au to be worth as much as $50 million.

That makes him wealthy even by the solid-gold standards of neighbouring Darling Point, Edgecliff and Rushcutters Bay, all in the same 2027 postcode.

NSW accounted for seven of the top 10 rated postcodes, while Victoria occupies two rungs at the top of the wealth ladder, according to the data released on Wednesday for the 2014-15 year.

That’s the upside. The other side of the coin is that the state also has the poorest postcodes, with the 132 residents of Bulyeroi, in the north-central part of the state, scraping by on an average taxable loss – yes, loss – of $8832.

That makes Bulyeroi the most down-at-heel town in the entire country.

Overall pauper honours, however, go to Queensland, where seven of the poorest postcodes are to be found. The other three entries at the bottom of the income ladder are all in NSW.

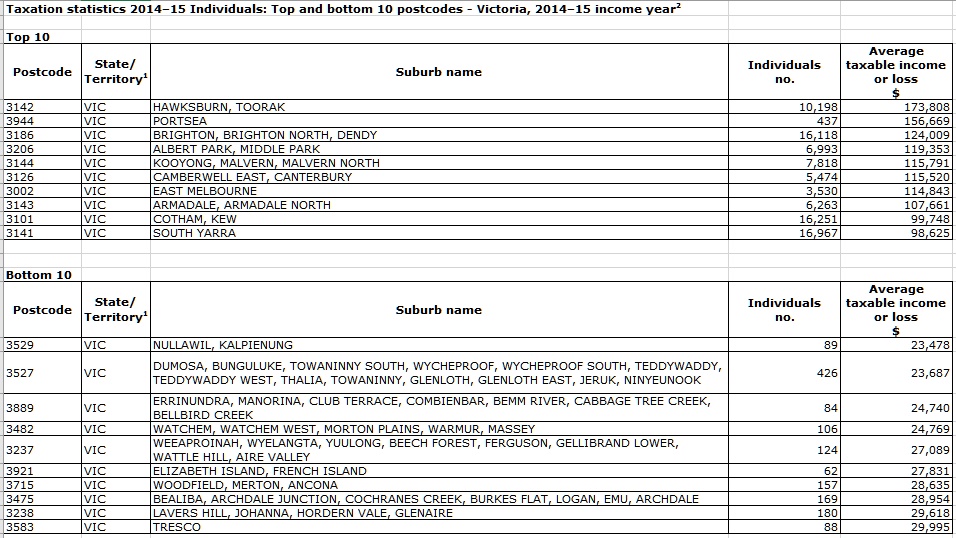

The Melbourne suburb of Toorak is the third-richest, with the Victorian seaside town of Portsea, grandly positioned at the entrance to Port Phillip Bay, ranking fifth in the wealth stakes.

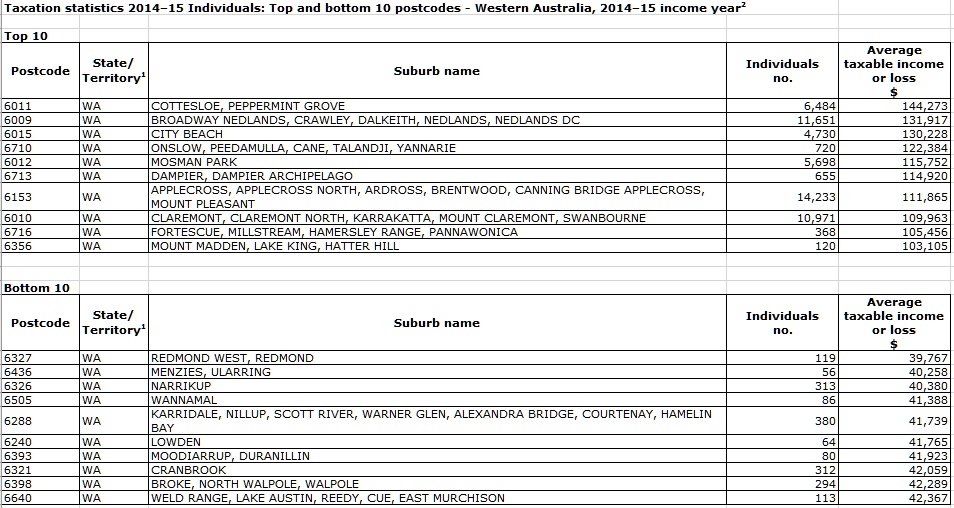

The only other state to figure in the top 10 was Western Australia, where Cottesloe/Peppermint Grove secured the ninth spot, just ahead of Sydney’s Woollahra on $144,273.

The most common professions reported among the top 10 postcodes included medical specialists and practitioners, financial dealers, psychiatrists, judicial and other legal professionals, mining engineers, chief managing directors, and engineering managers.

Surgeons were the highest earners, with an average taxable income of $377,044, followed by anaesthetists at $341,041.

Australia’s wealthiest postcodes, by suburb

- 2027 (NSW): Darling Point, Edgecliff, Hmas Rushcutters, Point Piper

- 2030 (NSW): Dover Heights, Hmas Watson, Rose Bay North, Vaucluse, Watsons Bay

- 3142 (VIC): Hawksburn, Toorak

- 2023 (NSW): Bellevue Hill

- 3944 (VIC): Portsea

- 2088 (NSW): Mosman, Spit Junction

- 2110 (NSW): Hunters Hill, Woolwich

- 2063 (NSW): Northbridge

- 6011 (WA): Cottesloe, Peppermint Grove

- 2025 (NSW): Woollahra

Australia’s poorest postcodes, by suburb

- 2387 (NSW): Bulyeroi, Rowena

- 4423 (QLD): Teelba, Glenmorgan

- 4489 (QLD): Wyandra

- 4467 (QLD): Mungallala, Tyrconnel, Redford

- 2386 (NSW): Burren Junction, Nowley, Drildool

- 2899 (NSW): Norfolk Island

- 4732 (QLD): Tablederry, Muttaburra

- 4424 (QLD): Glenaubyn, Drillham South, Drillham

- 4462 (QLD): Amby

- 4426 (QLD): Jackson, Jackson North, Jackson South

DFA notes this a TAXABLE INCOME, so after offsets and other tax saving measures. It tells you little about the status of gross household income.

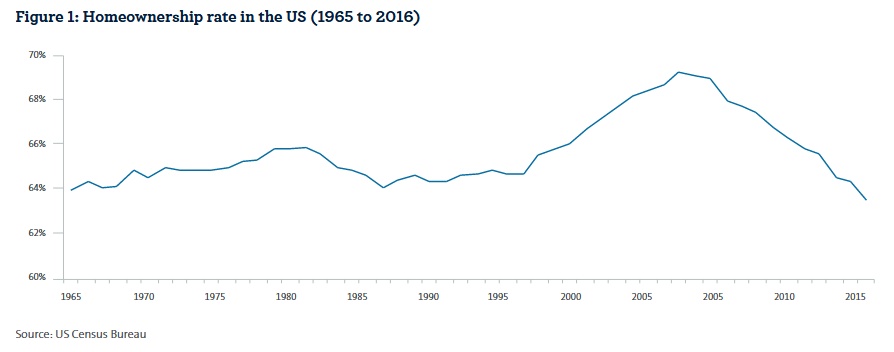

Generation Rent

A report by AMP says a major demographic shift in the US has contributed to a steady decline in home ownership since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), with Generation Y dubbed Generation Rent as millennials delay purchasing a home in the suburbs in favour of renting in the urban core.

A new AMP Capital whitepaper, Generation Rent, explores this trend, the implications for real estate investors and the opportunities within the US apartment REIT sector.

AMP Capital Client Portfolio Manager for Global Listed Real Estate and report author Chris Deves said: “The greater propensity for millennials to rent isn’t necessarily a surprise. After all, this is the same generation that pioneered the ‘sharing economy’, a collaborative approach to consumption, which draws heavily on the notion of renting.

“Millennials are opting for proximity to nightlife, restaurants and the workplace along with access to shared spaces and amenities, which is translating into greater demand for rented apartments in the urban core. As a demographic cohort, the strong willingness of millennials to relocate in the pursuit of new career opportunities necessitates flexibility and mobility, which is also more conducive to renting over owning.”

The paper shows this is an important tailwind for US apartment REITs, which make up roughly 8 per cent of the global listed real estate benchmark or more than US$100 billion of equity market capitalisation.

“On a through-cycle basis, this shift is a positive for residential landlords and, in turn, a positive for investors in the listed institutional apartment operators, which have asset portfolios with meaningful exposure to key urban centres.

“Apartment REITs are generally high quality and consolidation in the sector has left a set of large, well-capitalised companies with seasoned management teams, making them attractive for real estate investors with a long-term investment horizon,” Mr Deves said.

Mr Deves notes that millennials won’t, however, rent forever. He said: “The American dream of home ownership is not dead and buried. Gen Y are just as likely to head for the suburbs as previous generations, and starting a family is often an important catalyst. The key difference is that we are seeing this occur increasingly later in life.

“Cyclical affordability issues and demographic change has and will support demand for apartment rentals in city centres. During the property cycle, the US apartment REITs should therefore be in a stronger position to push rents, and quality management teams with insight into the needs of millennials will be best placed to deliver value for investors of all sizes.”

While the story is similar for Australian millennials, investing in the US is the best way to play this trend for local investors as it offers the largest, highest quality, and most liquid set of listed apartment landlords.

Mr Deves said: “Australian investors should consider a global strategy for listed real estate in order to access these kinds of thematics, which may not be as readily investible in their local market. A global approach also offers geographic diversification for the real estate portfolio.”

Time to end the Treasurer’s ‘housing supply’ con

When Derryn Hinch told the ABC on Monday that “owning your own home is not an Australian right”, he was unwittingly throwing his weight behind a huge con.

That con, in essence, is to convince voters that a major structural undersupply of dwellings is responsible for the current housing affordability crisis.

The argument is utterly bogus, though Mr Hinch may not yet understand why.

When asked if young Australians had “unrealistic expectations of where they can afford to buy homes close to the city”, he replied:

“You’re right. You’re 100 per cent right … it’s the expectation that, you know, here I am, I’m married, I’m da da da da, and therefore I should have a house.

“Now, in many European countries, and you look at places like New York City, most people – I think I’m right in saying this, or it was some years ago – most people rent, they don’t buy, they can’t afford it.”

Sounds reasonable, until you look at the number of Australian residents per dwelling.

Houses have grown a bit bigger on average, but even in ‘bubble state’ NSW the average number of residents per dwelling has been virtually flat since the millennium (see chart below).

And yet our political leaders, hand-in-glove with property developers and the banks, try to create the illogical impression that average house prices have risen because people want to live close to city centres.

Treasurer Scott Morrison told the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute in Melbourne on Monday that “… just over half of renters say they rent because they can’t afford to buy their own property”.

“Because of this, they are staying in the rental market for longer – a dynamic that puts upward pressure on rental prices and availability and even more pressure on lower-income households, increasing the need for affordable housing,” Mr Morrison said.

“Increasing numbers of higher income earners privately renting has the obvious effect of lowering availability of affordable rental stock to those on low incomes.”

The Treasurer’s logic is completely flawed.

When a renter becomes a home owner, they vacate one property and occupy another. When a high-income earner sells their home and decides to rent, they vacate one property and occupy another.

The average number of Australian residents per dwelling is not affected by that process.

If immigration, or the birth and death rates, ever get substantially ahead of the national supply of housing stock, that really would be a supply issue – we’ll know more about that when the second round of 2016 census data is released in June.

But until that happens, rising prices in one area should be offset by fewer dollars chasing properties in another area.

So why does that not happen?

Well actually, it does. House prices are falling in Perth, for instance, as mining-related workers head east to look for new jobs. Rental vacancies in that city have risen from around 1 per cent to 5 per cent in the past four years.

But those relative shifts between one capital city and another, or between inner and outer suburbs, have been dwarfed in the post-millennium era by the credit bubble that began to grow when generous discounts to capital gains tax were legislated in 1999.

Twin distortions

The 50 per cent CGT discount, combined with existing negative gearing provisions, meant that property investors could afford to borrow more to bid up house prices. As they did so, owner-occupiers were forced to try to match them.

The entire market has been lifted, like a harbour full of different-sized boats, by the same tide – cheap credit and ridiculously generous tax incentives for investors.

The two most important causes of the housing affordability crisis are, therefore, the ones Mr Morrison has already vowed not to reform.

To make planned affordability measures in this year’s budget seem plausible, Mr Morrison’s housing supply con must be maintained.

Mr Hinch should not join that effort. Owning your own home may not be an Australian right, but shopping for a home in a market that is not systematically distorted to benefit investors, developers and banks certainly is.

First results from the 2016 Census

In a country as diverse as Australia, it is impossible to identify a set of characteristics that defines us. However, with today’s release of data from the 2016 Census, it is possible to identify some of the common characteristics, how they vary across states and territories, and how they are changing over time.

Australia undertakes a compulsory long-form census – where detailed information across several areas is required of every individual respondent – every five years.

Australia undertakes a compulsory long-form census – where detailed information across several areas is required of every individual respondent – every five years.

So, what did we learn from the first set of results? According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS):

The 2016 Census has revealed the ‘typical’ Australian is a 38-year-old female who was born in Australia, and is of English ancestry. She is married and lives in a couple family with two children and has completed Year 12. She lives in a house with three bedrooms and two motor vehicles.

Australia is getting a bit older; the typical Australian in 2011 was aged 37.

How do today’s results vary across Australia?

First, age varies by state and territory.

With variables like age, we often find the “typical” value by taking the median. In essence, we (statistically) line everyone up from youngest to oldest, and find the person who is older than half the population but younger than the other half.

In Tasmania, the median age among 2016 Census respondents was 42. But in the Northern Territory, it was 34. Those in Australian Capital Territory were also quite young (median age 35), whereas those in South Australia were relatively old (40).

The NT population’s relatively young age is influenced by the very high proportion that identify as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander.

While we don’t have updated estimates for that proportion (either for the NT or nationally), the data released today show that the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population is quite young. The median age nationally is 23. New South Wales and Queensland have the youngest Indigenous population, with a median age of 22.

This release also tells us something about the different migrant profiles across Australia. Nationally, the most common country of birth for migrants is England. And the median age of migrants is much older than for the Australian-born population (44 compared to 38).

The most common country of birth for migrants living in Queensland was New Zealand; in Victoria it was India; in NSW it was China. There may not be too many more censuses until the most common migrant nationally was not born in England.

Ahead of the forthcoming federal budget, there has been a lot of media and policy attention on housing affordability. Today’s release of census data points to some subtle differences across Australia that may influence policy responses.

Nationally, the most common tenure type is owning a three-bedroom home with a mortgage. In Queensland, however, renters make up a roughly equal share of the population. But, in Tasmania and NSW, more people own their own home outright. And in the NT, renting is the most common tenure type.

In a finding that won’t surprise many, the typical female does a bit more unpaid work around the house than the typical male. The most common category for males is less than five hours a week. The most common for females is five to 14 hours.

We won’t know how this compares to paid work for a while yet – or whether these differences vary depending on age.

What future releases will tell us

The profiles released today offer us limited information. But the census remains one of Australia’s most important datasets.

When detailed data are released in June and then progressively throughout the rest of 2017, we will be able to dig deeper into small geographic areas or specific population groups.

We will be able to ask if there are pockets of Australia with significant socioeconomic disadvantage, and if it is worsening. We will be able to hold governments accountable for the progress we have made on the education, employment and health outcomes of the Indigenous population.

And we will be able to test whether the languages we speak, the houses we are living in, and the jobs that we are doing, are changing.

But those questions rely on a high-quality census.

The attention on the 2016 Census until now has been mostly negative. There was increased concern related to data privacy, the failure of the online data entry system on census night, and staff cuts at the ABS.

In October 2016, the ABS estimated the response rate to the 2016 Census was more than 96%, and that 58% of the household forms received were submitted online. But what matters more than how many people filled in the census and how they did it is whether the responses given were accurate. We therefore need to see a lot more interrogation of the data before taking the results at face value, but we can remain cautiously optimistic.

The ABS will be hoping that now some data is released, attention will shift to what the results tell us about Australian society. It is to be hoped the data will be robust, the insights will be newsworthy, and policy and practice will shift accordingly.

We won’t know this for sure until the first major data release of data June 27 – the data released today were just a sneak peak.

Author: Nicholas Biddle, Associate Professor, ANU College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University