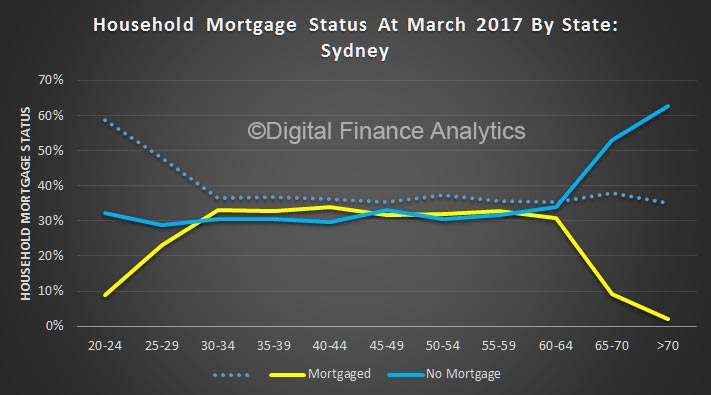

Sydney’s population has officially reached 5 million, according to figures released today by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). This is one key reason why demand for property is so strong here.

ABS Director of Demography, Beidar Cho, said that at 30 June 2016, 5,005,400 people lived in the NSW capital – up 82,800 from the previous year.

“It took Sydney almost 30 years, from 1971 to 2000, to grow from 3 million to 4 million people, but only half that time to reach its next million,” she said.

Today’s figures show that Melbourne is Australia’s fastest growing capital city. Its population grew by 2.4 per cent in 2015-16, ahead of Brisbane (1.8 per cent) and Sydney (1.7 per cent). Australia’s slowest growing capital city was Adelaide, at below 1 per cent.

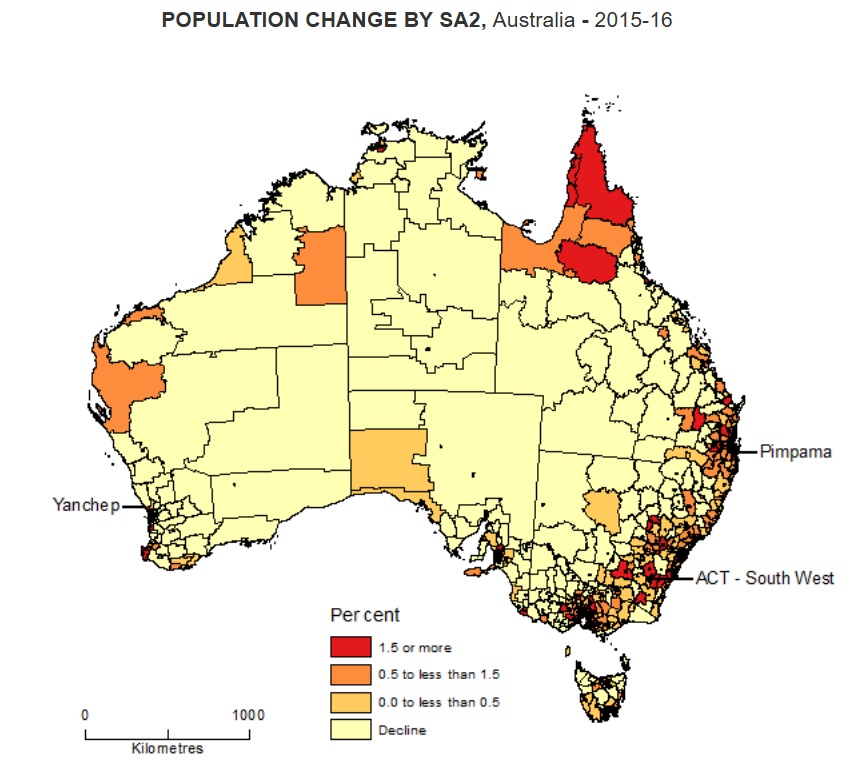

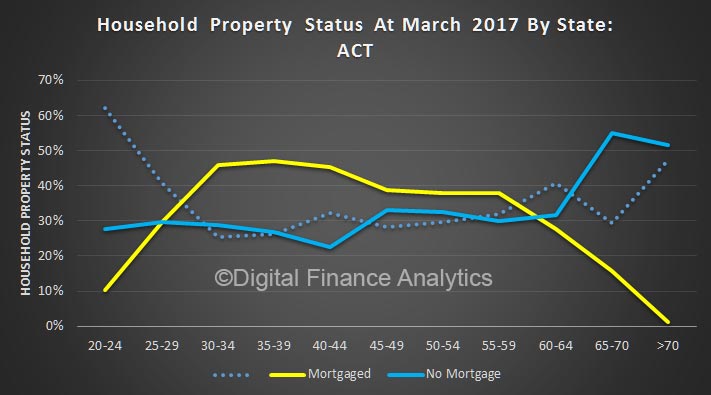

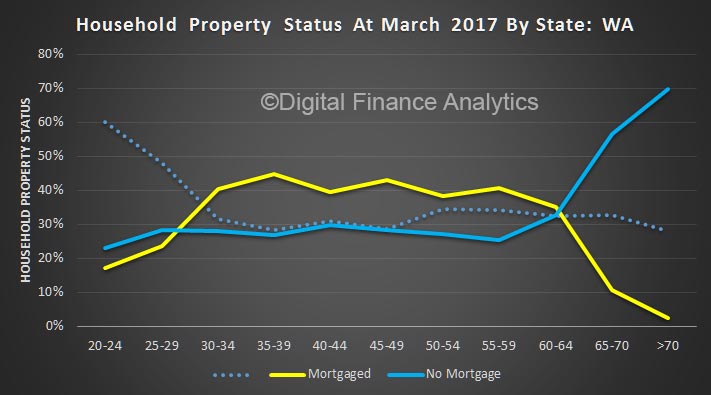

The fastest growing area in Australia in 2015-16 was ACT – South West, which grew by 38 per cent. This area includes the recently developed suburbs of Wright and Coombs. Other areas experiencing fast growth included Pimpama (35 per cent) on the Gold Coast, the coastal area of Yanchep (29 per cent) in Perth’s north and Cobbitty – Leppington (28 per cent) in Sydney’s outer south-west.

- Australia’s estimated resident population (ERP) reached 24.1 million at 30 June 2016, increasing by 337,800 people or 1.4% since 30 June 2015. This growth rate was unchanged from 2014-15.

- All states and territories experienced population growth between 2015 and 2016. Victoria had the greatest growth (123,100 people), followed by New South Wales (105,600) and Queensland (64,700).

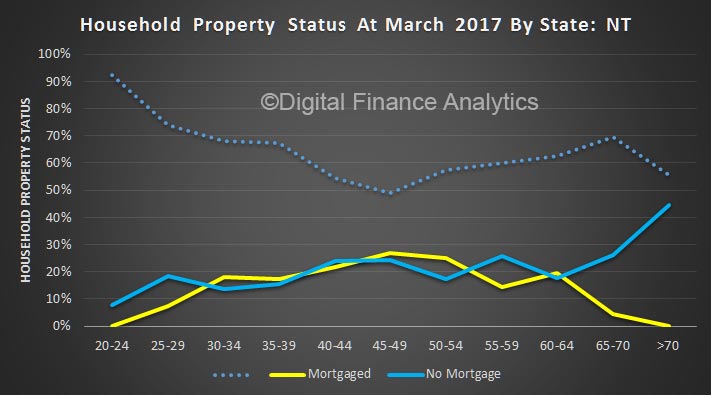

- Victoria also grew fastest, increasing by 2.1%, followed by New South Wales and Queensland (both 1.4%), the Australian Capital Territory (1.3%) and Western Australia (1.0%). The Northern Territory had the slowest growth (0.2%), followed by South Australia and Tasmania (both 0.5%).

- The combined population of Greater Capital Cities increased by 276,500 people (1.7%) between 30 June 2015 and 30 June 2016, accounting for 82% of the country’s total population growth.

- Melbourne had the largest growth of all Greater Capital Cities (107,800), followed by Sydney (82,800), Brisbane (41,100) and Perth (27,400).

- Melbourne also had the fastest growth (2.4%), ahead of Brisbane (1.8%) and Sydney (1.7%).

- Sydney’s population reached 5 million in 2015-16. While it took almost 30 years (1971 to 2000) for Sydney’s population to increase from 3 million to 4 million people, it took only another 16 years to reach its next million.