The story of contemporary globalisation is, at its heart, the story of how we created a vast and impoverished working class. It is abundantly clear that the dynamics behind this have now hit home. First Brexit, then Donald Trump. We have been told that these votes were a primal scream from those forgotten parts of society.

Both campaigns identified immigration as a core cause of worker impoverishment and social exclusion. Both argued that limiting immigration would reverse these disempowering trends. It is true that poverty remains high and has even been expanding in the UKand the US, but the cause, and the solution, lie far deeper.

According to the charity Oxfam, one in five of the UK population live below the official poverty line, meaning that they experience life as a daily struggle. In the US, the richest country in world history, one in five children live in poverty. In the UK, austerity has played a role but is not the only cause. According to a Poverty and Social Exclusion project published early in George Osborne’s first wave of austerity, the proportion of households that fell below society’s minimum standards had already doubled since 1983.

Poverty pay and working conditions are proliferating across the UK. A recent study of the clothing manufacturing sector around the city of Leicester found that employers often consider welfare benefits as a “wage component”, forcing workers to supplement sub-minimum wage pay with welfare benefits. In this sector 75-90% of workers earn an average wage of £3 an hour. Companies get round the law by paying cash-in-hand and by grossly under-recording the hours worked.

Worker rights no longer set in stone. Martyn Jandula/Shutterstock

Recent news about working conditions at Sports Direct, Hermes, Amazon, and others show that far from being an isolated case, the Leicester example is part of an increasingly common trend towards low-wage, exploitative practices, greatly facilitated by a state-directed reduction in trade union power.

Income attacks

Mainstream portrayals of globalisation present it as a relatively benign market expansion and deepening. But this misses out the bedrock upon which such growth occurs: the labour of new working classes.

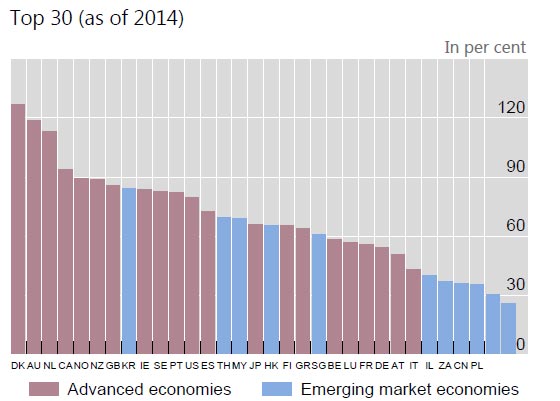

Following the end of the Cold War, the global incorporation of the Chinese, Indian and Russian economies served to double the world’s labour supply. De-peasantisation and the establishment of export processing zones across much of Latin America, Africa and Asia has enlarged it even further. The International Monetary Fund calculates that number of workers in export-orientated industries quadrupled between 1980 and 2003.

This global working class subsists upon poverty wages. Forget the problems in the clothing sector around Leicester, The Clean Clothes Campaign found that textile workers’ minimum wages across Asia equate to as little as 19% of their basic living requirements. To survive they must work many hours overtime, purchase low quality food and clothing, and forego many basic goods and services.

Cut from the same cloth? Workers in Asia. Asian Development Bank/Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND

A core element of globalisation has been the outsourcing of production from relatively high-wage northern economies to these poverty-wage southern economies. This enables firms to pay workers on the other side of the world 20 to 30 times less than former, “native” workers. They can then pocket the very significant cost difference in profits. For example, Apple’s profits for the iPhone in 2010 constituted over 58% of the device’s final sale price, while Chinese workers’ share was only 1.8%.

Outsourcing is celebrated by proponents of globalisation because, they argue, rather than produce goods expensively, they can be imported much more cheaply. This is true for many economic sectors in the global north, of course, but the downside is that wages and working conditions in remaining jobs are subject to colossal downward pressure.

Not working

What can be done? Limiting immigration will have no effect on these global dynamics, and may exacerbate them. You see, if wages are pushed up by labour shortages after any block on immigration, then the pressure and the incentive for firms to further outsource production, or to relocate, will increase. The anti-immigrant rhetoric and the mooted solutions of Donald Trump, UKIP, and much of the UK Conservative party will not help native workers one bit. Nor are they intended to. Rather, they represent a divisive political strategy designed to keep at bay any criticism of a decades-long assault on workers’ organisations.

Trump’s solutions don’t solve the problem. EPA/MIKE NELSON

For a problem brought about by globalisation it should shock no one that the progressive solution to poverty wages at home and abroad must be a global one. One thing that could work is the establishment of living wages across global supply chains. This would increase the price of labour in the global south, which in turn would limit some of the downward pressures that poverty wages here exert upon global north workers’ pay and conditions.

Doubling the wages of Mexican sweatshop workers would increase the cost of clothes sold in the US by only 1.8%. Increasing them ten-fold would raise costs by 18%. That cost increase can either be borne by northern consumers, who are themselves increasingly suffering from the wage-depressing dynamics of globalisation, or by reducing, only slightly, outsourcing firms’ profits. The outcome depends on politics and an understanding from voters that the dynamics that pushed towards Brexit and Trump are rooted in the systemic dynamics of corporate-driven globalisation. Contrary to its supporters claims, this mode of human development is based upon the degradation of labour worldwide.

The key question here is whether companies can be convinced to raise, significantly, their workers’ wages? Given capitalism’s cut-throat competitive dynamics, probably not right now. But there are many workers’ organisations toiling to achieve such objectives across the globe. Recognising that success in these struggles would contribute to improving the conditions for workers in the global north is a small, but necessary, first step towards realising these goals.

The Lend Lease housing development in London is designed to provide affordable housing but also ensure profits for developers. Picture: Ella Pellegrini

The Lend Lease housing development in London is designed to provide affordable housing but also ensure profits for developers. Picture: Ella Pellegrini