From The Conversation.

Over the last few years, we’ve seen a massive shift in the way we work. Thousands of Australians have abandoned the traditional 40-hour work week to work fewer hours or take on ad-hoc work, such as driving for Uber or doing odd jobs on Airtasker.

But the way we measure the labour market has not kept up. We still rely on the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ labour force survey, a survey from the 1960s conducted according to international conventions that is no longer appropriate for today’s labour market.

Today’s economy – one of independent contractors, ad-hoc work, irregular and flexible hours – needs a new form of measurement.

How the government measures the workforce

Every month the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) surveys about 0.32% of the civilian population aged over 15 years about their employment status.

In short, you’re counted as employed if you completed at least one hour of paid work in the week before the survey.

But this doesn’t sound quite right. Clearly, one hour of paid work per week doesn’t fit most people’s idea of employment.

In fact, over one million workers are counted as “underemployed”, meaning they would work more hours if they could. This raises the question of whether these people should really be considered “employed”. The answer depends on what policy question you are trying to address.

Is our unemployment rate right?

Let’s get right into how our unemployment rate is calculated.

If respondents haven’t done any paid work in the last week, they are asked two further questions – first, have they actively sought work in the last four weeks, and second, are they currently available to start work? They are only considered unemployed if they answer yes to both of these questions. Otherwise, they’re not counted as part of the labour force.

This means full-time homemakers, carers, the ill and non-working retirees aren’t considered unemployed.

The labour force is the sum of the employed and the unemployed. The unemployment rate is the percentage of the labour force who are unemployed.

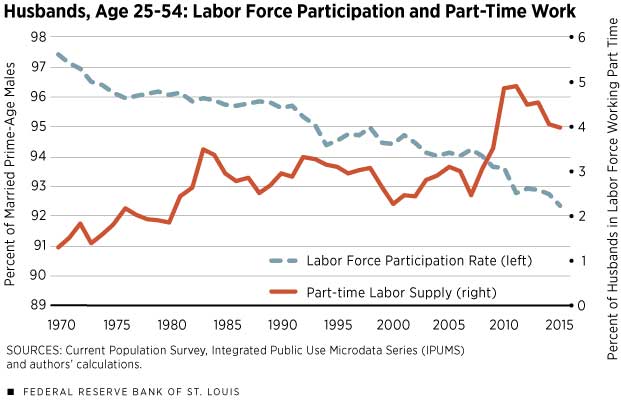

Lastly, the participation rate is the percentage of the population aged 15 and older who are in the labour force. According to the latest ABS trend estimates, the participation rate stood at 64.5% in November, no change from October.

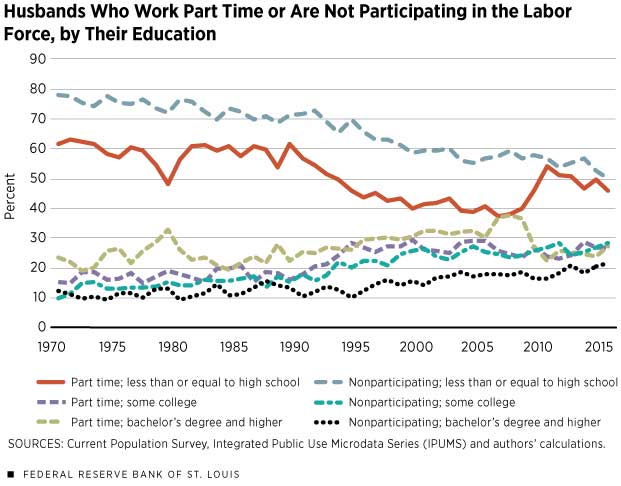

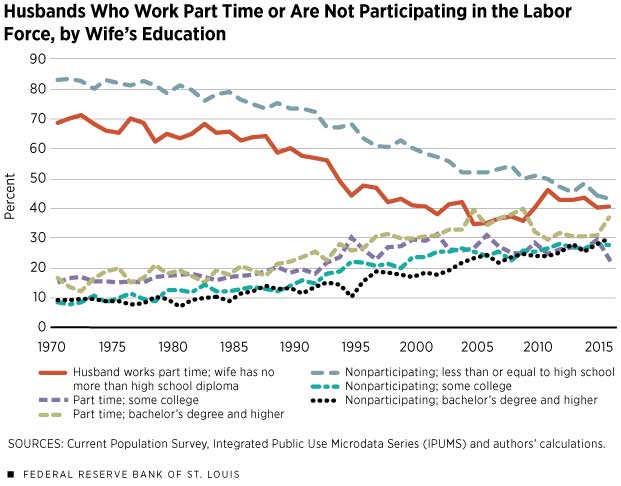

The participation rate has been consistently trending upwards over time for women and falling for men. This does not mean women are increasingly doing more work but that over time they have switched from unpaid to paid work. One of the main reasons for falling participation among men is that unskilled manual jobs for older men have been declining over several decades and many men have been reclassified as unemployed, disabled or retired.

More issues with the survey

The Labour Force Survey only provides a measure of employment and not the number of jobs. For example, a person might work 20 hours per week at a supermarket and 10 hours per week as an Uber driver. Employment is always classified according to the “main job”, so the ABS deems them as one person employed part-time (working fewer than 35 hours) in the retail industry.

If that person worked five more hours as an Uber driver the next week, they would be classified as full-time (35 hours) but the supermarket job would still determine the industry in which they are employed.

The crucial problem here is that there are two jobs being done, but the ABS employment estimate only counts one. So be wary of commentators and politicians making statements like “the economy gained/lost 10,000 jobs last month”! What jobs are they measuring?

The labour force survey also fails to make distinctions between different types of workers. About two million Australians work as independent contractors like construction workers or other business operators such as hairdressers working from home. However, in the figures they are not distinguished from regular employees.

Whereas it might be relatively easy for an employee to know if they did any paid work in the week before the survey, it might not be so obvious for a non-employee. For instance, an author might work 50 hours on their book one week and three hours the next. Most of their work is basic research rather than writing. They receive a royalty payment twice a year. How would they answer the question of whether they did any paid work in the last week?

For non-employees the question of whether they are prepared to start work and have been actively looking for work can also be complex. Someone doing consultancy work might not actively look for work because clients seek them out instead.

We need something new

The ABS has tried tackling some of these issues by conducting some different surveys, including the Characteristics of Employment Survey which presents information on all employed persons according to their status of employment. However, the framework classifies jobholders by their main job. That is, only the job in which they usually worked the most hours. This doesn’t capture many of the issues of concern in, say, the “sharing” or “gig” economy

The ABS has also attempted to compare the number of filled jobs to the amount of employed people, using estimates in the labour force survey. This can reveal interesting information about the labour market. For instance, in February 2013 there were 11,628,300 employed people in Australia, but an estimated 12,287,200 filled jobs. That is, there were 658,900 more filled jobs than there were employed people.

But even then, the estimates still use the conventional definition of a job.

The ABS is still working on an Australian Labour Market Account, based on International Labor Organisation (ILO) methodology, which may address some of the issues discussed here. But this will still be based on traditional definitions of jobs, employment, and unemployment.

Our conventional employment measures are no longer equipped to inform us about important aspects of our labour force and a reliance on them could lead to inappropriate policy. We need labour force numbers than can capture the nuances of a modern economy.