It is well-known that the labor force participation rate for men and the hours worked by men have declined over the past four decades. More men are reporting that they either are not employed and not actively searching for a job or are working part time; these two trends are contributing to the decline in the average hours worked by men in the past four or five decades.

During this same time, women have increased their representation in the labor market: The fraction of women participating in the labor force has increased, as has the number of hours women work outside the home, with the majority of the increases driven by growth in the labor supply of married women.

The changes in the labor supply of men and women may be related, especially if we consider married men and women. Time allocation—that is, how much a spouse works, how much time each spends on housework and child care, and how much leisure each enjoys—is decided within households. This context is needed to analyze married individuals’ decisions to withdraw from the labor market or to work part time. Although many papers have documented the decline in the labor supply of males, this article focuses on the changing role of wives in providing economic support for their families and changes in the labor supply of prime-age (25-54) married males.

We focus on prime-age married males because of this group’s traditional role of being the breadwinners; these men are typically attached to the labor market and work full time.

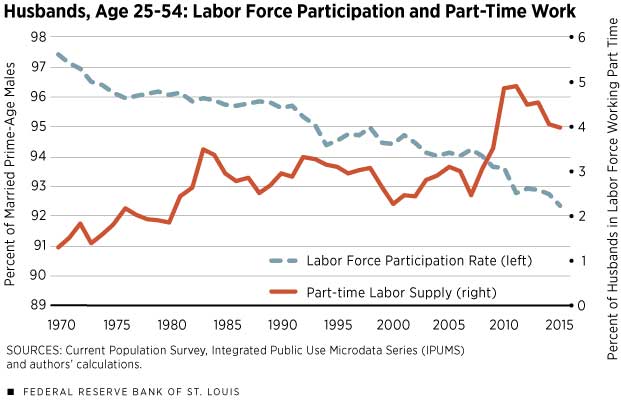

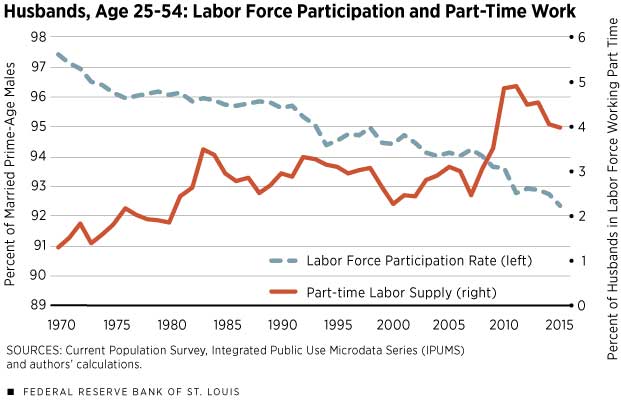

This shows changes in the labor force participation rate of this group. The trend is similar to that for men in general. In 1970, more than 97 percent of these husbands participated in the labor market, dropping below 93 percent in 2011 and staying there. Meanwhile, the rate of part-time workers among prime-age husbands increased substantially since the 1970s: Less than 1.5 percent of the men worked part time in 1970; this fraction has been about 4 percent or more since 2009. As for wives, close to 26 percent of married women in the labor force worked part time in 1970, but only about 22 percent worked part time after 2000.

This shows changes in the labor force participation rate of this group. The trend is similar to that for men in general. In 1970, more than 97 percent of these husbands participated in the labor market, dropping below 93 percent in 2011 and staying there. Meanwhile, the rate of part-time workers among prime-age husbands increased substantially since the 1970s: Less than 1.5 percent of the men worked part time in 1970; this fraction has been about 4 percent or more since 2009. As for wives, close to 26 percent of married women in the labor force worked part time in 1970, but only about 22 percent worked part time after 2000.

Household Labor Supply

Several factors could contribute to the decline in labor force participation and hours worked by married prime-age men and to the increase in labor supply of their wives. The explanations include both demand- and supply-side motives. One explanation for the declines related to men is that there is a drop in demand, especially in the manufacturing sector; this decline in demand is related to skill bias, technological changes and offshoring. The increase in married female labor supply can be partly explained by the increase in educational attainment of women and the increase in relative wages in high-skill occupations.

In the context of household labor supply, however, a decline in the gender pay gap can cause an increase in the female labor supply and a decrease in the male labor supply as a response to the household’s joint decision on labor and to the household’s overall income. In other words, the higher income generated by wives may reduce the incentive of husbands to work many hours or to work at all.

Furthermore, increases in labor force participation of married women and their hours worked can also be due to an increase in risk pooling in households, especially in households in which women are married to low-skilled men or to men working in declining industries. With women’s strides in education, they can provide insurance within the household by working more when men lose their jobs or when the wages offered to men are low. This insurance motive may kick in even before the husband loses his job. Wives may decide to work outside the home when there is just a threat of unemployment or a decline in their husbands’ earnings.

Another possible explanation for the increase in married males’ working part time has to do with the fact that finding jobs can take time and effort. Working part time allows the individual to spend more time searching for a better-paying job or investing in the acquisition and enhancement of skills, which often means going back to school or even acquiring skills that allow individuals to change occupation or sector. Thus, in households in which wives work full time, husbands might be able to be choosier in accepting jobs—they can afford to be less willing to take full-time jobs for low pay or jobs that may not offer good promotion prospects or other nonpecuniary qualities. These men may take part-time jobs while searching for better jobs.

Next, we explore changes in characteristics of households in which prime-age men were not participating in the labor force or worked part time between 1970 and 2015.

Labor Supply and Education Composition

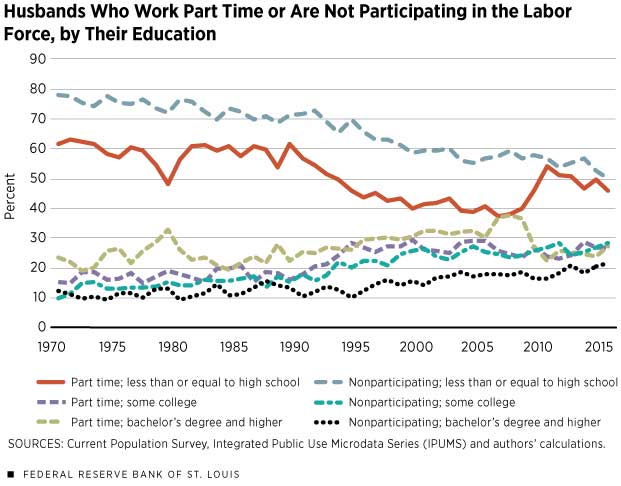

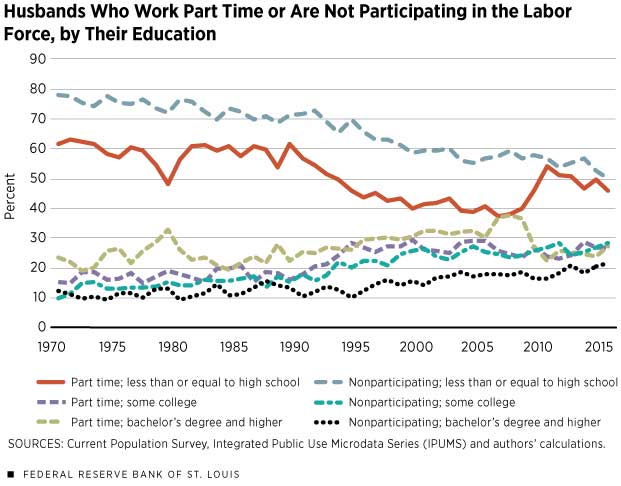

The education composition of husbands who either work part time or are nonparticipating has changed significantly over time.

As shown above, in both groups, the respective fraction of husbands with high school education or less decreased, and the fraction of husbands with at least some college education increased since 1970. (During and after the Great Recession of 2007-09, however, the fraction of males who worked part time and had no more than a high school diploma went up but has since reverted to its decreasing trend. As for better-educated husbands, there was a relative decline in the fraction working part time during the recession. The differences between the experiences of the two groups during the recession can be due to the differences in the demand for the skills of educated and less-educated men; another factor is that more-educated husbands are more likely to have more-educated wives with different labor market prospects.)

As shown above, in both groups, the respective fraction of husbands with high school education or less decreased, and the fraction of husbands with at least some college education increased since 1970. (During and after the Great Recession of 2007-09, however, the fraction of males who worked part time and had no more than a high school diploma went up but has since reverted to its decreasing trend. As for better-educated husbands, there was a relative decline in the fraction working part time during the recession. The differences between the experiences of the two groups during the recession can be due to the differences in the demand for the skills of educated and less-educated men; another factor is that more-educated husbands are more likely to have more-educated wives with different labor market prospects.)

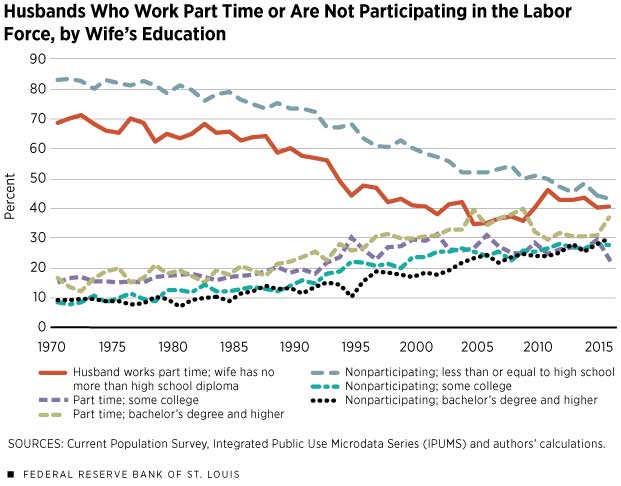

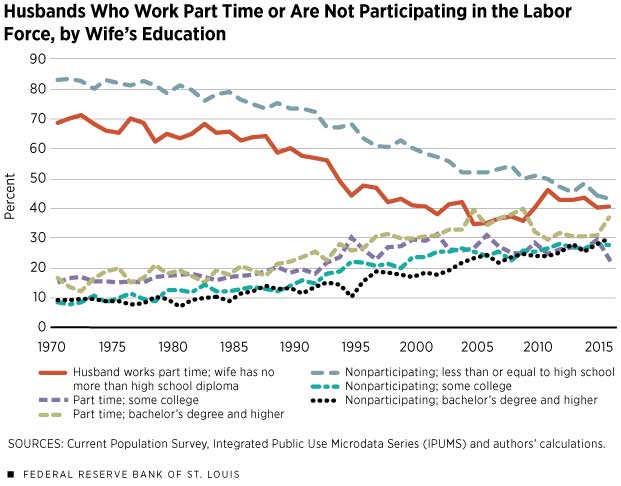

To further explore the changes in the composition of households in which husbands do not participate in the labor force or work part time, we turn to the education compositions of the wives.

This demonstrates, the fraction of these husbands who are married to women with high school education or less declined significantly. The fact that women in households in which males work part time or do not participate are more educated than in the past (and given the decline in the gender earnings gap) may imply that these women are more likely to work, earn relatively more and provide more economic support for their families.

This demonstrates, the fraction of these husbands who are married to women with high school education or less declined significantly. The fact that women in households in which males work part time or do not participate are more educated than in the past (and given the decline in the gender earnings gap) may imply that these women are more likely to work, earn relatively more and provide more economic support for their families.

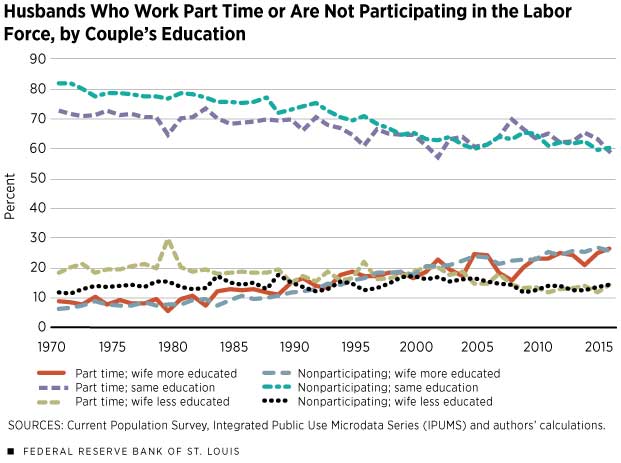

In addition to the education composition of the men and women, the relative earning potential of the spouses in the household can be important to understanding how the spouses allocate their time among jobs, housework, child care and leisure.

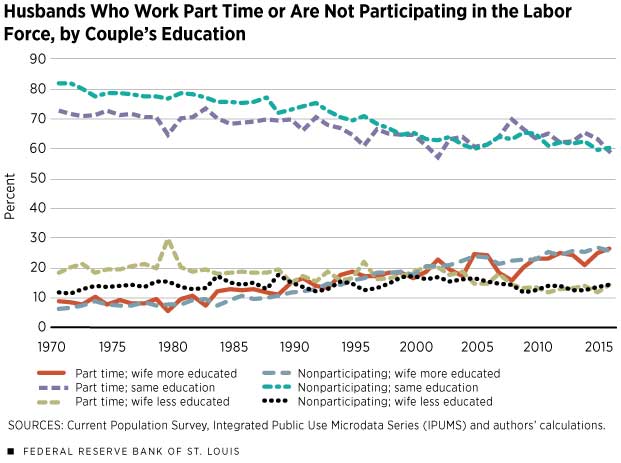

This presents the change in composition of part-time and nonparticipating husbands by their education status relative to that of their wives. Interestingly, among these two groups of men, there is a clear decline in those who are married to women with the same education level or less and an increase in the fraction of those who are married to women who are more educated than they are. The percentage of those married to wives who are relatively more educated than them increased from about 9 percent in 1970 to about 27 percent in 2015.

This presents the change in composition of part-time and nonparticipating husbands by their education status relative to that of their wives. Interestingly, among these two groups of men, there is a clear decline in those who are married to women with the same education level or less and an increase in the fraction of those who are married to women who are more educated than they are. The percentage of those married to wives who are relatively more educated than them increased from about 9 percent in 1970 to about 27 percent in 2015.

The patterns in both increasing education of women in households in which men work part-time jobs and the fact that in an increasing fraction of these households women are more educated than the men suggest that the earning potential of women in these households is higher than it used to be. These patterns also suggest that these women might have better labor market prospects than men and have an important role in providing economic support for their families.

Relative Share of Wives’ Earnings

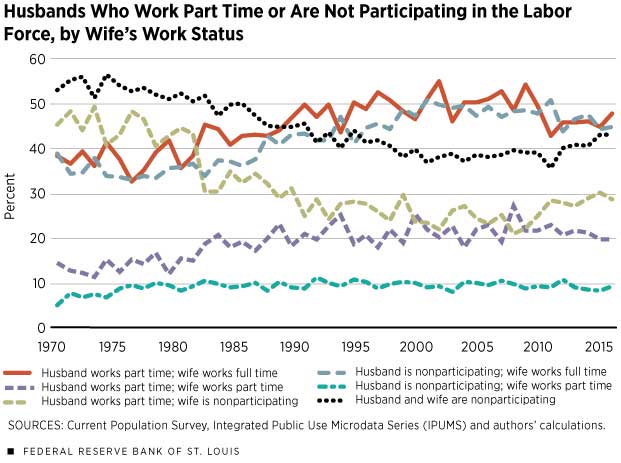

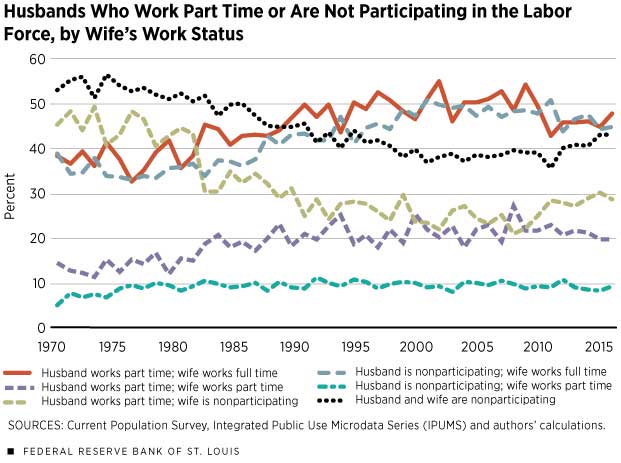

This describes the employment status of women in households in which the husbands work part time or are nonparticipating. Despite the short dip after the Great Recession, the overall increasing trend of the fraction of men who work part time and are married to women who work full time is clear. The patterns for wives of nonparticipating husbands are similar.

This describes the employment status of women in households in which the husbands work part time or are nonparticipating. Despite the short dip after the Great Recession, the overall increasing trend of the fraction of men who work part time and are married to women who work full time is clear. The patterns for wives of nonparticipating husbands are similar.

Next, we describe the role of the wife’s income relative to the husband’s income and how that relationship changed over time.

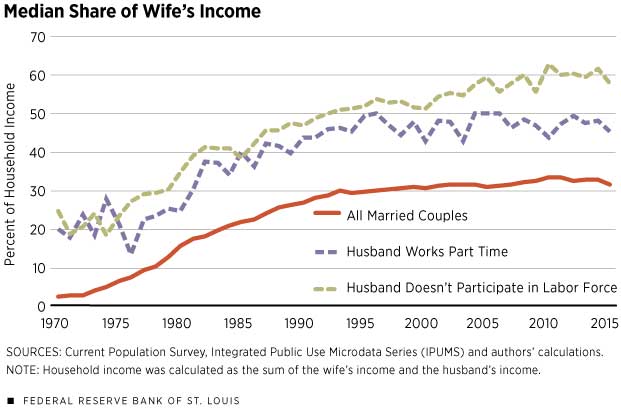

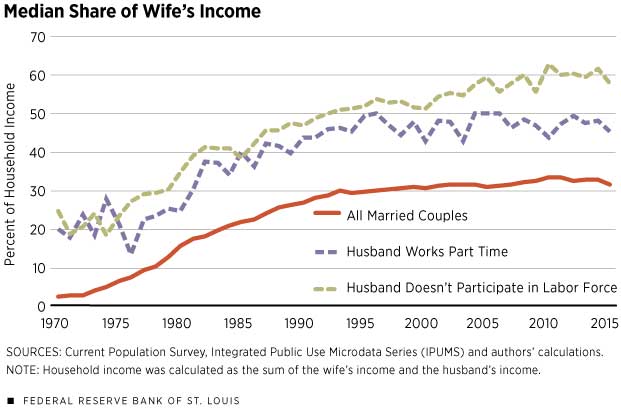

This shows the median share of the wife’s income in the total household income for married households. In the overall sample, the share was close to 2 percent in 1970, which is consistent with traditional families in which the men are the breadwinners. This share rose to about 30 percent by the late 1990s and has fluctuated around 30 percent since then. The share of the wife’s income in families with husbands who work part time or are nonparticipating is always higher than the share of the wife’s income in all married families. However, in families in which men work part time or do not participate, the wife’s income in recent years has been equal to or has exceeded that of the husband.

This shows the median share of the wife’s income in the total household income for married households. In the overall sample, the share was close to 2 percent in 1970, which is consistent with traditional families in which the men are the breadwinners. This share rose to about 30 percent by the late 1990s and has fluctuated around 30 percent since then. The share of the wife’s income in families with husbands who work part time or are nonparticipating is always higher than the share of the wife’s income in all married families. However, in families in which men work part time or do not participate, the wife’s income in recent years has been equal to or has exceeded that of the husband.

Conclusion

Despite the findings that most of the increase in nonparticipation of prime-age males stems from relatively less-educated males,9 the fraction of educated, prime-age husbands who do not participate or who work part time has increased over the past few decades. At the same time, in these households, the fraction of educated women and the fraction of women who are more educated than their husbands increased.

Increase in nonparticipation of prime-age males stems from relatively less-educated males, the fraction of educated, prime-age husbands who do not participate or who work part time has increased over the past few decades. At the same time, in these households, the fraction of educated women and the fraction of women who are more educated than their husbands increased.

These data partly reflect decades of demographic changes: rising college graduation rates in the overall population, with women’s educational achievements surpassing men’s; a decline in the marriage rate, especially for those with less education; and changes in the marriage markets. Thus, the composition of the households in which males do not work or who work part time has also changed. We found that in these households the role of women in providing income to the family is higher than it was in the past. These changes are likely to affect households’ labor supply and job-search behavior (the intensity of search and what kinds of jobs and pay people are willing to accept).

In addition, the data show that changes in labor supply during and right after the Great Recession vary by the education of the spouses: The fraction of males working part time who had no more than a high school education or who were married to women with no more than a high school education increased during the recession; meanwhile, the fraction of better-educated males working part time and of males working part time who were married to better-educated females declined during the recession, suggesting differences in both labor market opportunities and labor-search behavior for more-educated families.

Although many papers suggest that the role of the changes in labor demand is important, the descriptive analysis cannot be used to infer causal effect and to separate demand and supply factors. However, it is important to assess the role of the marriage market and the role of both spouses in generating income and providing housework in order to fully understand trends in labor participation and hours worked and how they interact with business cycles and labor market conditions.

In particular, assessment is needed of job-search behavior and the choice of sector in which people want to work. Whether to remain in a sector with high probability of unemployment or to acquire new skills, whether to work outside the home and, if so, how many hours to work—all of these decisions for husbands may depend on their wives’ employment opportunities, as well as their own employment opportunities.

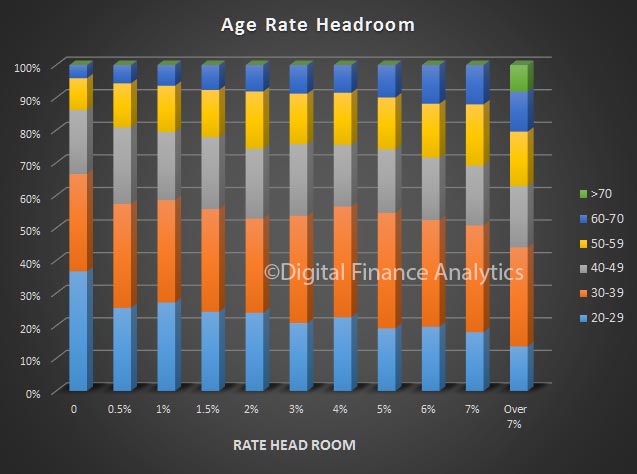

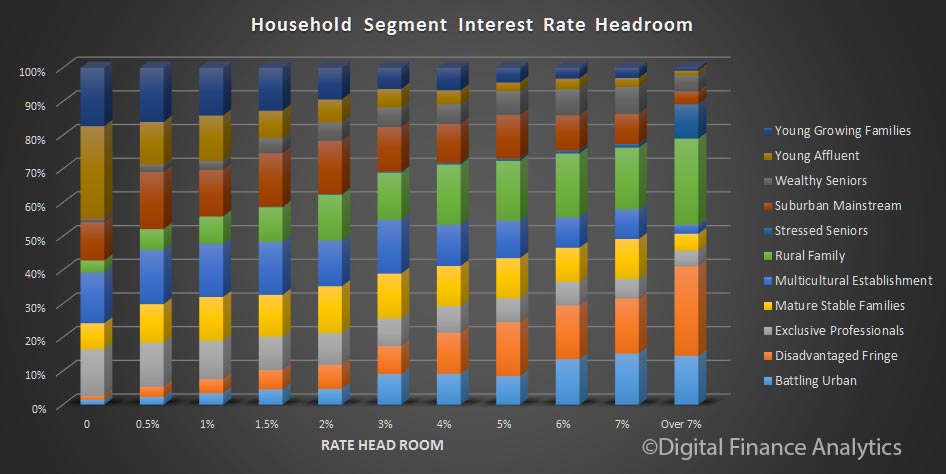

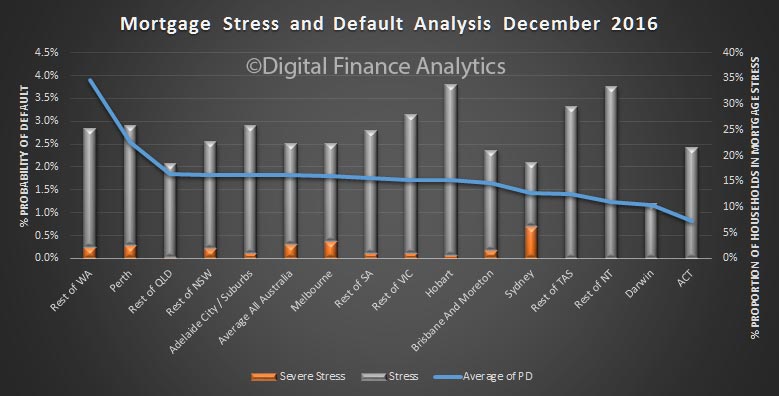

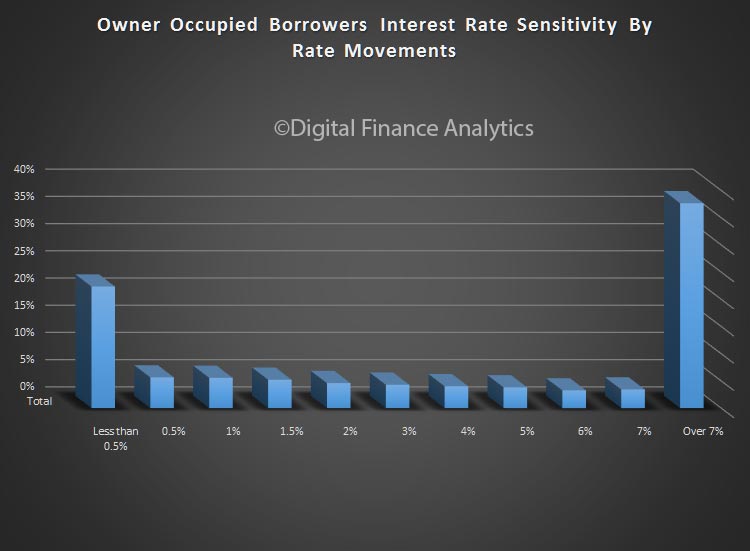

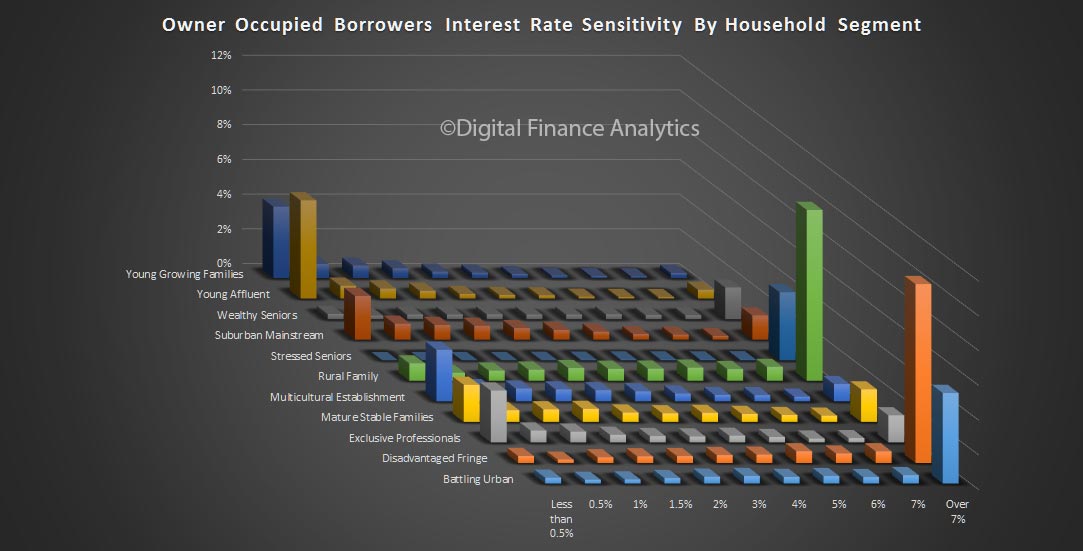

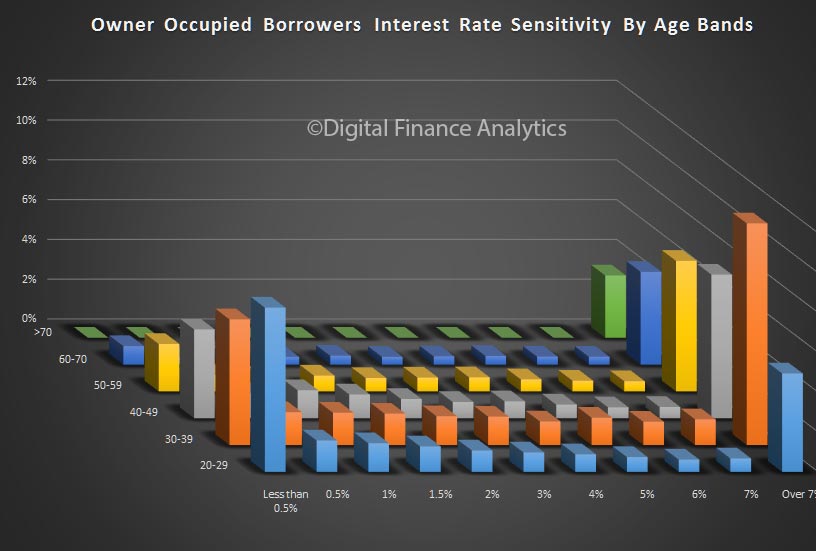

If we overlay our household segments, we find that young growing families and young affluent households are most exposed to a small rate rise. However, some in other segments are also at risk.

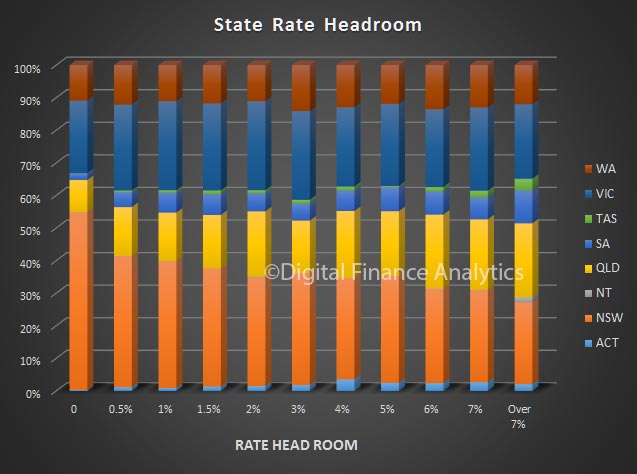

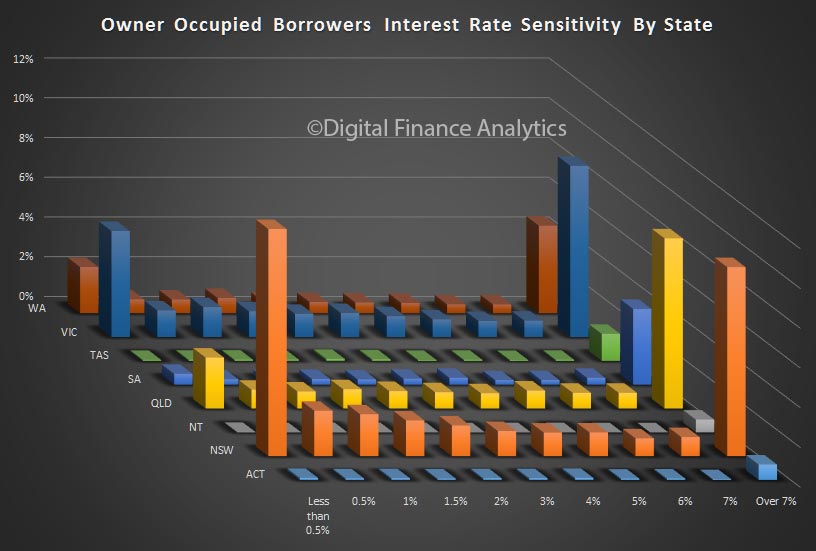

If we overlay our household segments, we find that young growing families and young affluent households are most exposed to a small rate rise. However, some in other segments are also at risk. State analysis highlights that households in NSW are most sensitive, a combination of larger volumes of loans as well a larger loans, relative to incomes resulting is less headroom.

State analysis highlights that households in NSW are most sensitive, a combination of larger volumes of loans as well a larger loans, relative to incomes resulting is less headroom. Younger households are relatively more exposed, because their incomes tend to be more limited and are not growing in real terms relative to mortgage repayments.

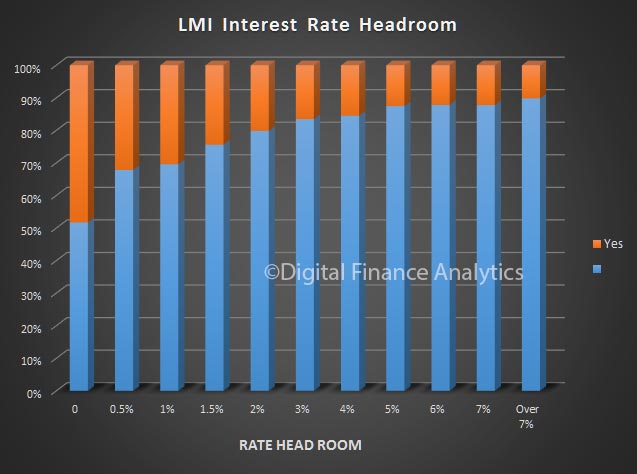

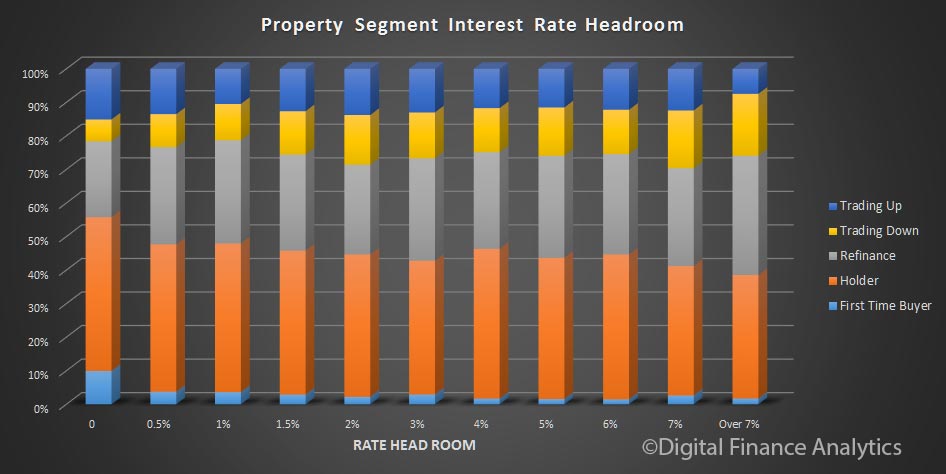

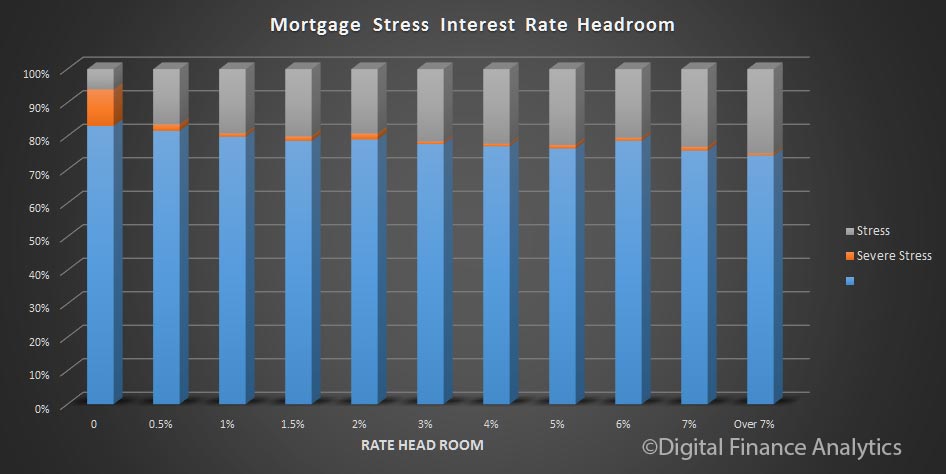

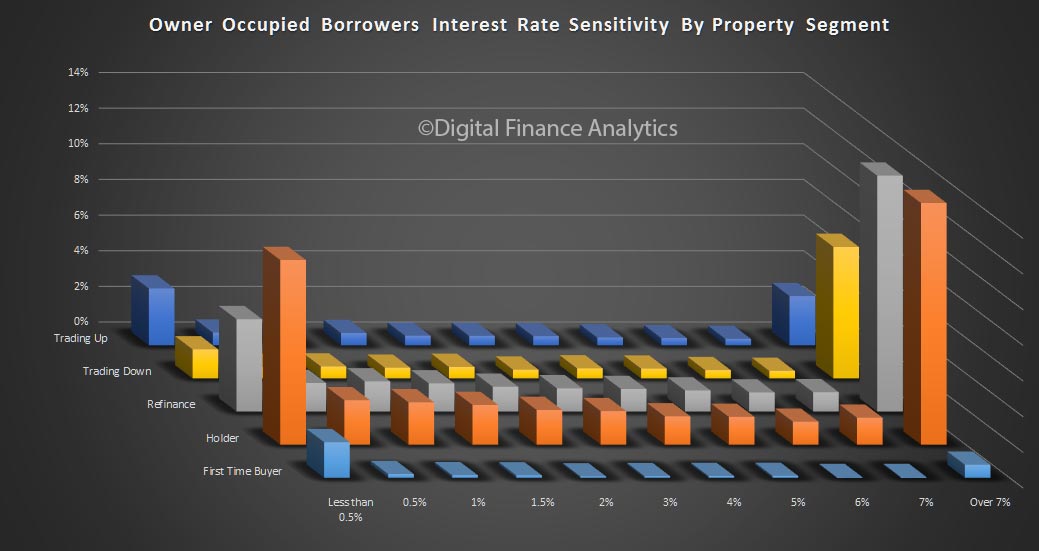

Younger households are relatively more exposed, because their incomes tend to be more limited and are not growing in real terms relative to mortgage repayments. Analysis by DFA property segment shows that whilst some first time buyers are exposed at low rate movements, those holding a mortgage with no plans to change their properties (holders) are also exposed. In addition, some seeking to refinance are doing so in the hope of reducing payments, because they have limited headroom.

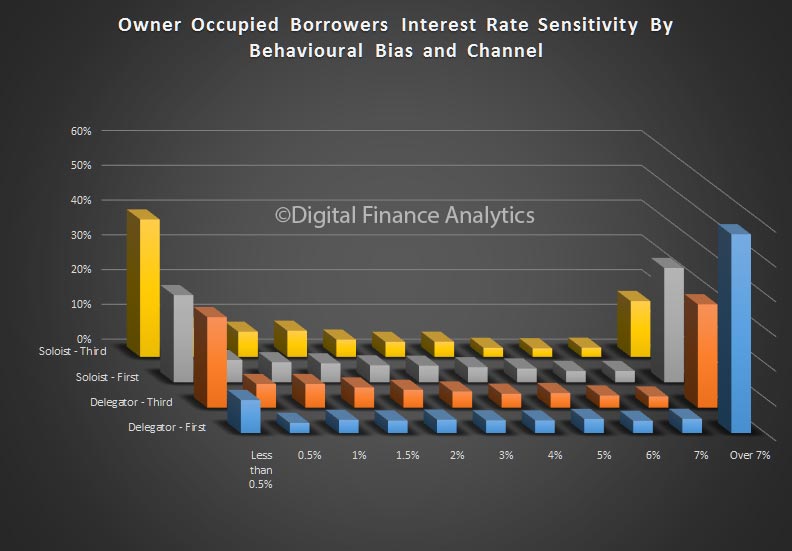

Analysis by DFA property segment shows that whilst some first time buyers are exposed at low rate movements, those holding a mortgage with no plans to change their properties (holders) are also exposed. In addition, some seeking to refinance are doing so in the hope of reducing payments, because they have limited headroom. Finally we turn to other insights from our data. First, those households who sourced their mortgage via a mortgage broker are more likely to be in difficulty with a small rate rise, compared with those who went direct to a bank. This, once again, shows third party loans are more risky. This perhaps is connected to the types of people using brokers, as well as the broker’s ability to suggest lenders with more generous underwriting standards and coaching on how to apply successfully.

Finally we turn to other insights from our data. First, those households who sourced their mortgage via a mortgage broker are more likely to be in difficulty with a small rate rise, compared with those who went direct to a bank. This, once again, shows third party loans are more risky. This perhaps is connected to the types of people using brokers, as well as the broker’s ability to suggest lenders with more generous underwriting standards and coaching on how to apply successfully. Soloists who went via a broker are the most exposed should rates rise even a little, whereas delegators going to a bank, are more able to handle future rises.

Soloists who went via a broker are the most exposed should rates rise even a little, whereas delegators going to a bank, are more able to handle future rises.