The Reserve Bank of New Zealand has published a Bulletin article on “An international comparison of inflation-targeting frameworks“. The article compares the inflation-targeting frameworks of 10 advanced economy central banks.

The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (‘RBNZ’) began targeting inflation as a mechanism to ensure price stability in 1988. The RBNZ’s inflation target framework was then formalised with the Reserve Bank of New Zealand Act (1989) and when the first Policy Targets Agreement (‘PTA’) was set in 1990. The Bank of Canada was the second central bank to target inflation, in order to achieve price stability, in 1991. Since then inflation targeting has become internationally regarded as a conventional monetary policy framework. Inflation-targeting frameworks have continued to evolve based on individual country experiences; consequently it is useful to periodically compare the formal and informal inflation-targeting frameworks across advanced economies and understand the key similarities and differences. A previous article by Wood and Reddell (2014) compared the goals for monetary policy across inflation-targeting countries by focusing on primary legislation. This article expands on that analysis by comparing the inflation-targeting frameworks, including informal frameworks, with actual practices.

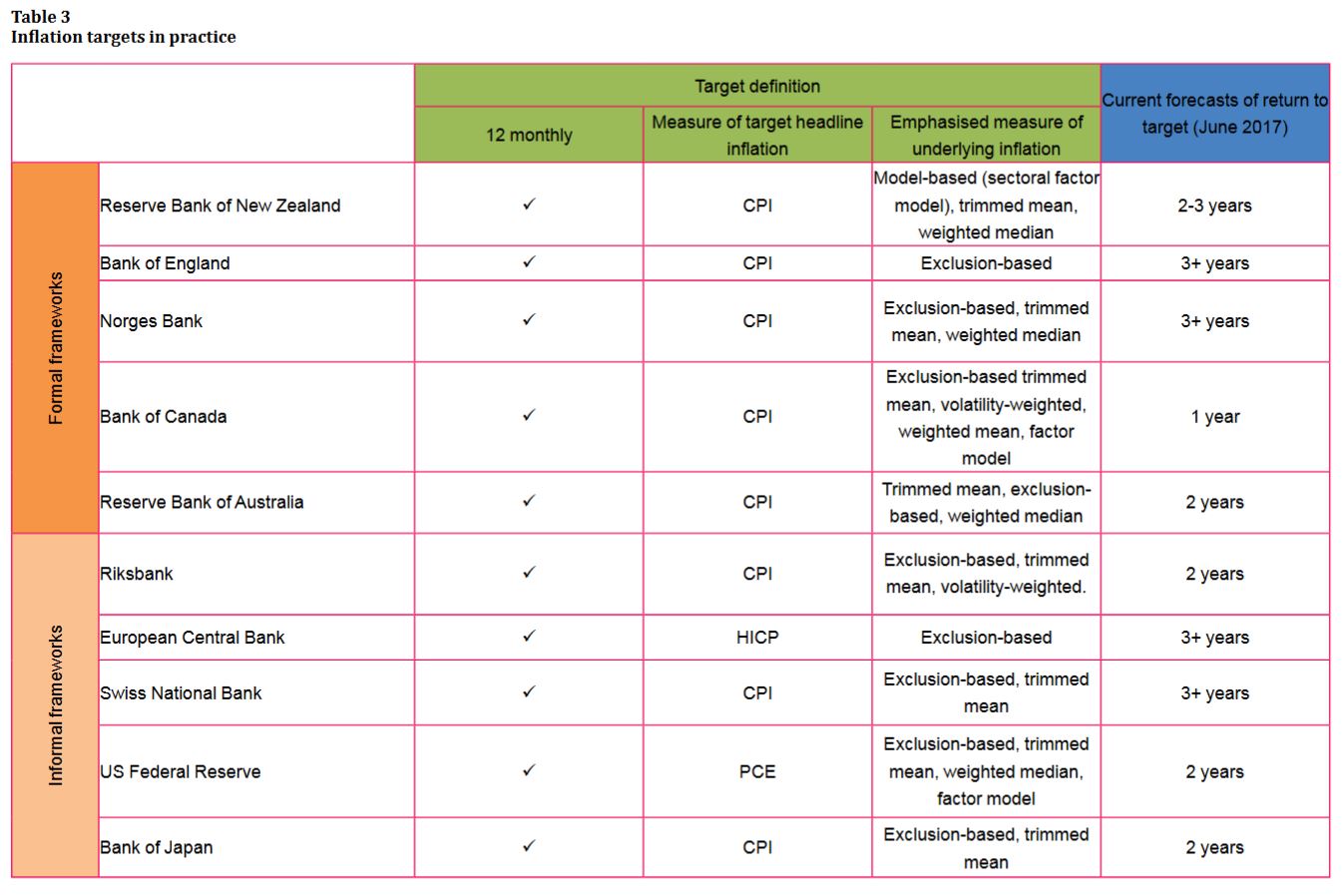

This article compares the frameworks and practices of 10 advanced economies that employ either full or partial inflation targeting. This includes six ‘fully fledged’ inflation-targeting central banks: Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Bank of England (‘BoE’), Norges Bank, the Bank of Canada (‘BoC’), the Reserve Bank of Australia (‘RBA’), and Sveriges Riksbank (‘Riksbank’). These banks explicitly target inflation over a specified time frame in order to achieve price stability, have monetary policy independence, regularly announce monetary policy decisions, and are accountable for policy decisions. Several large central banks also use elements of inflation targeting without either explicitly announcing an inflation target, or they have other objectives alongside low and stable inflation. These are the European Central Bank (‘ECB’), the Swiss National Bank (‘SNB’), the United States Federal Reserve (‘Fed’), and the Bank of Japan (‘BoJ’). Given their importance to international monetary policy, we also assess their frameworks and practices.

The comparison covers five components of an inflation-targeting framework: inflation target definition, communication of monetary policy, secondary considerations5, assessment of the inflation-targeting performance, and framework reviews and revisions. The comparison reveals four key findings.

- Despite large differences across inflation-targeting frameworks, the central banks operate and communicate monetary policy similarly.

- The central banks pursue forward-looking inflation targets and produce reports that support ex ante and ex post performance

- The central banks take account of secondary considerations when setting monetary policy, but not all inflation-targeting frameworks detail how central banks should make these secondary considerations, particularly with regard to financial stability.

- Several countries have published reviews of and made revisions to their inflation-targeting frameworks. However, the revisions to the frameworks are not always based on recommendations from published reviews.

The most striking observation from the paper however is the fact that most of the central banks do not expect inflation to return to target any time soon.

This would imply lower interest rates for longer, despite asset price bubbles. This begs the question, is inflation targetting really good and effective policy?

This would imply lower interest rates for longer, despite asset price bubbles. This begs the question, is inflation targetting really good and effective policy?