On 17 August, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the central bank, announced reforms to the loan prime rate (LPR) mechanism. Via Moody’s.

Beginning on 20 August, the new LPR will average the lending rate quoted by 18 banks on that same day to determine the lending rate for all banks when they originate new floating rate loans. This process will then be repeated on the 20th of each month.

This reform will narrow Chinese banks’ lending margins, a credit negative. The narrower margins on loans will also encourage banks to increase their risk appetite and, as a result, weaken asset quality.

According to the PBOC, the National Interbank Funding Center will announce the new LPR at 9.30am on the 20th of every month.

A five-year tenor will be added to the existing one-year LPR to serve as a reference rate for banks pricing long-term loans such as mortgages. To expand the representativeness of the LPR, the PBOC also included eight small banks – including two city commercial banks, two rural commercial banks, two foreign banks and two private-invested banks – to the existing 10, including state-owned and joint stock commercial banks, participating in LPR quotations. Banks’ use of LPR as a pricing reference will be included into and evaluated by China’s Macro Prudential Assessment.

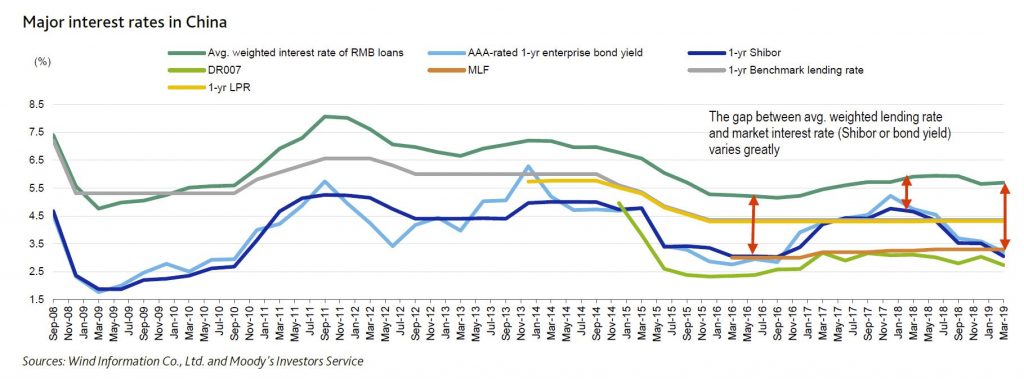

The new mechanism liberalizes interest rates because it will explicitly replace the current loan pricing based on benchmark rates, which are not sensitive to changes in market rates. Under the current practice, introduced in October 2013, 10 banks decide the LPR on a daily basis. This gives them little incentive to price their LPR differently than the PBOC’s benchmark lending rate, which has not changed since October 2015. Although this mechanism was designed to approximate market-oriented interest rates, the actual rate has closely matched the government’s benchmark lending rate. In recent months money market rates and bond yields have declined substantially but actual bank loan rates have remained high, resulting in a wider gap above market interest rates, protecting Chinese banks’ lending margins.

The new LPR formation will be based on open market operations (OMO) rates, mainly the one-year interest rate of the medium-term lending facility (MLF) combined with a premium to reflect bank’s own funding cost, risk premium and credit supply and demand. The PBOC created the MLF in September 2014 to provide banks with medium-term funding typically for three-months to one-year. As of 15 August, the MLF interest rate is 3.3%. We expect the PBOC will increase the frequency to adjust the MLF interest rate to better reflect market rates.

Because of current market conditions, the implementation of the new LPR loan pricing mechanism will directly weigh on bank rates on new loans and lower their net interest margins. We expect that the banks with large loan exposures due for re-pricing in the near-term will be more immediately exposed. The actual impact over time will also be affected by differences in bank’s asset mix, revenue mix, the credit profile of borrowers and cost management.

We expect that the banks’ narrowing margins on traditional loans will prompt some banks to increase their risk appetite, potentially weakening asset quality. For example, banks could shift their investment portfolios to high yield bonds and other high-yield investments from low yield Treasury bonds and investment-grade bonds.

From a risk-management perspective, the new mechanism, by making loan rates more responsive to market rates, will increase banks’ exposure to market volatility and interest rate risk. The lack of a developed interest rate derivative market in China will add to this pressure by limiting banks’ ability to hedge or transfer this risk.