The BIS – The Central Bankers’ Banker, has released a report “The Green Swan“, in which they discuss the issue of ” Central banking and financial stability in the age of climate change”. Specifically they warn that expecting Central Banks to do “Green QE” to mitigate financial risks relating to climate variation is unrealistic, saying that while banks in financial distress in an ordinary crisis can be resolved, this will be far more difficult in the case of economies that are no longer viable because of climate change. Intervening as climate rescuers of last resort could therefore affect central bank’s credibility and crudely expose the limited substitutability between financial and natural capital. This is more evidence of the pressures building to react to climate variability. Hence, climate-related risks are a source of financial risk.

They conclude: while climate change risk management policy could drag central banks into uncharted waters: on the one hand, they cannot simply sit still until other branches of government jump into action; on the other, the precedent of unconventional monetary policies of the past decade (following the 2007–08 Great Financial Crisis), may put strong sociopolitical pressure on central banks to take on new roles like addressing climate change. Such calls are excessive and unfair to the extent that the instruments that central banks and supervisors have at their disposal cannot substitute for the many areas of interventions that are necessary to achieve a global low-carbon transition. But these calls might be voiced regardless, precisely because of the procrastination that has been the dominant modus operandi of many governments for quite a while. The prime responsibility for ensuring a successful low-carbon transition rests with other branches of government, and insufficient action on their part puts central banks at risk of no longer being able to deliver on their mandates of financial (and price) stability”.

Now, let me add that I have read widely on this issue, and have looked at the data – I find the evidence for greater energy in the climate system convincing. In terms of the underlying causes, my view is some can be traced to natural variation, but this does not explain the correlations we are seeing, thus I have concluded that human activity is also adding to the problem. While we cannot control the natural variations, we can and should tackle that which we can address. Hence my stance. This is the biggest challenge we face, frankly. But the polarisation between “deniers and believers” is a false politically led dichotomy. This is not a religion!

David Wallace-Wells recently observed in The Uninhabitable Earth (2019), “We have done as much damage to the fate of the planet and its ability to sustain human life and civilization since Al Gore published his first book on the climate than in all the centuries – all the millenniums – that came before.”

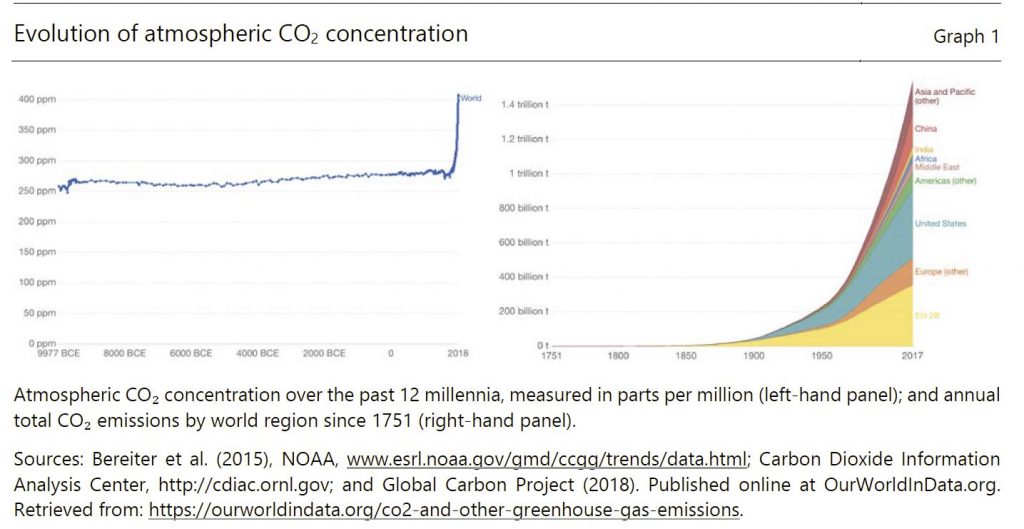

The BIS says that climate change poses an unprecedented challenge to the governance of global socioeconomic and financial systems. Our current production and consumption patterns cause unsustainable emissions of greenhouse gases (GHGs), especially carbon dioxide (CO2): their accumulated concentration in the atmosphere above critical thresholds is increasingly recognised as being beyond our ecosystem’s absorptive and recycling capabilities. The continued increase in temperatures has already started affecting ecosystems and socioeconomic systems across the world but, alarmingly, climate science indicates that the worst impacts are yet to come. These include sea level rise, increases in weather extremes, droughts and floods, and soil erosion. Associated impacts could include a massive extinction of wildlife, as well as sharp increases in human migration, conflicts, poverty and inequality.

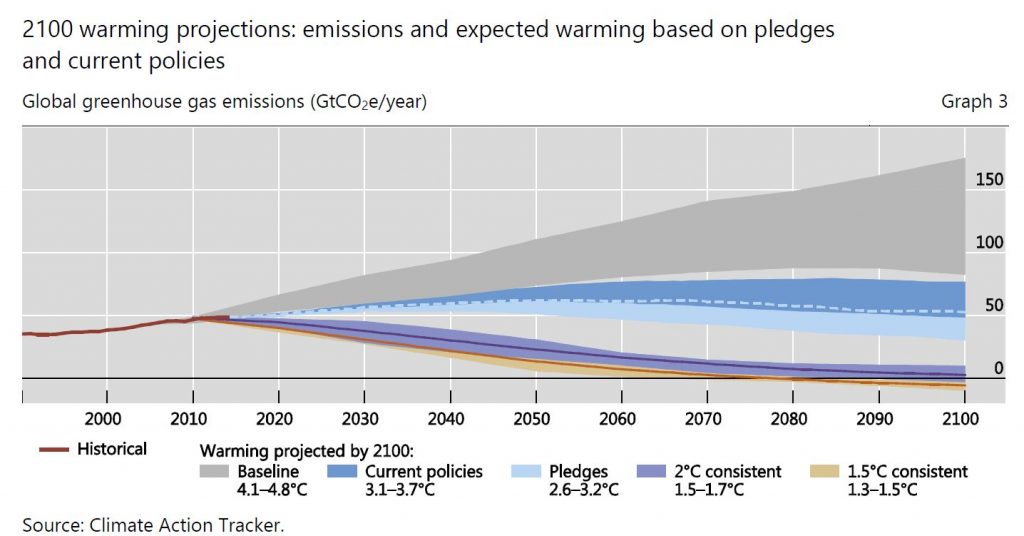

Scientists today recommend reducing GHG emissions, starting immediately. In this regard, the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference and resulting Paris Agreement among 196 countries to reduce GHG emissions on a global scale was a major political achievement. Under the Paris Agreement signatories agree to reduce greenhouse gas emissions “as soon as possible” and to do their best to keep global warming “to well below 2 degrees” Celsius (2°C), with the aim of limiting the increase to 1.5°C. Yet global emissions have kept rising since then and nothing indicates that this trend is reverting. Countries’ already planned production of coal, oil and gas is inconsistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C or 2°C, thus creating a “production gap”, a discrepancy between government plans and coherent decarbonisation pathways.

Changing our production and consumption patterns and our lifestyles to transition to a low-carbon economy is a tough collective action problem. There is still considerable uncertainty on the effects of climate change and on the most urgent priorities. There will be winners and losers from climate change mitigation, exacerbating free rider problems. And, perhaps even more problematically, there are large time lags before climate damages become apparent and irreversible (especially to climate change sceptics): the most damaging effects will be felt beyond the traditional time horizons of policymakers and other economic and financial decision-makers. This is what Mark Carney referred to as “the tragedy of the horizon”: while the physical impacts of climate change will be felt over a long-term horizon, with massive costs and possible civilisational impacts on future generations, the time horizon in which financial, economic and political players plan and act is much shorter. For instance, the time horizon of rating

Ominously, David Wallace-Wells recently observed in The Uninhabitable Earth (2019), “We have done as much damage to the fate of the planet and its ability to sustain human life and civilization since Al Gore published his first book on the climate than in all the centuries – all the millenniums – that came before.”

Our framing of the problem is that climate change represents a green swan – it is a new type of systemic risk that involves interacting, nonlinear, fundamentally unpredictable, environmental, social, economic and geopolitical dynamics, which are irreversibly transformed by the growing concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Climate-related risks are not simply black swans, ie tail risk events. With the complex chain reactions between degraded ecological conditions and unpredictable social, economic and political responses, with the risk of triggering tipping points, climate change represents a colossal and potentially irreversible risk of staggering complexity.

Revisiting financial stability in the age of climate change

The reflections on the relationship between climate change and the financial system are still in their early stages: despite rare warnings on the significant risks that climate change could pose to the financial system, the subject was mostly seen as a fringe topic until a few years ago. But the situation has changed radically in recent times, as climate change’s potentially disruptive impacts on the financial system have started to become more apparent, and the role of the financial system in mitigating climate change has been recognised.

This growing awareness of the financial risks posed by climate change can be related to three main developments. First, the Paris Agreement’s Article 2.1(c) explicitly recognised the need to “mak[e] finance flows compatible with a pathway toward low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development”, thereby paving the way to a radical reorientation of capital allocation. Second, the Governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney suggested the possibility of a systemic financial crisis caused by climate-related events. Third, in December 2017 the Central Banks and Supervisors Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) was created by a group of central banks and supervisors willing to contribute to the development of environment and climate risk management in the financial sector, and to mobilise mainstream finance to support the transition toward a sustainable economy.

The NGFS quickly acknowledged that “climate-related risks are a source of financial risk. It is therefore within the mandates of central banks and supervisors to ensure the financial system is resilient to these risks”. The NGFS also acknowledged that these risks are tied to complex layers of interactions between the macroeconomic, financial and climate systems (NGFS.

As this book will extensively discuss, assessing climate-related risks involves dealing with multiple forces that interact with one another, causing dynamic, nonlinear and disruptive dynamics that can affect the solvency of financial and non-financial firms, as well as households’ and sovereigns’ creditworthiness.

In the worst case scenario, central banks may have to confront a situation where they are called upon by their local constituencies to intervene as climate rescuers of last resort For example, a new financial crisis caused by green swan events severely affecting the financial health of the banking and insurance sectors could force central banks to intervene and buy a large set of carbon-intensive assets and/or assets stricken by physical impacts.

But there is a key difference between green swan and black swan events: since the accumulation of atmospheric CO2 beyond certain thresholds can lead to irreversible impacts, the biophysical causes of the crisis will be difficult, if not impossible, to undo at a later stage. Similarly, in the case of a crisis triggered by a rapid transition to a low-carbon economy, there would be little ground for central banks to rescue the holders of assets in carbon-intensive companies. While banks in financial distress in an ordinary crisis can be resolved, this will be far more difficult in the case of economies that are no longer viable because of climate change. Intervening as climate rescuers of last resort could therefore affect central bank’s credibility and crudely expose the limited substitutability between financial and natural capital.

Given the severity of these risks, the uncertainty involved and the awareness of the interventions of central banks following the 2007–08 Great Financial Crisis, the sociopolitical pressure is already mounting to make central banks (perhaps again) the “only game in town” and to substitute for other if not all government interventions, this time to fight climate change. For instance, it has been suggested that central banks could engage in “green quantitative easing”10 in order to solve the complex socioeconomic problems related to a low-carbon transition.

Relying too much on central banks would be misguided for many reasons. First, it may distort markets further and create disincentives: the instruments that central banks and supervisors have at their disposal cannot substitute for the many areas of interventions that are needed to transition to a global low-carbon economy. That includes fiscal, regulatory and standard-setting authorities in the real and financial world whose actions should reinforce each other. Second, and perhaps most importantly, it risks overburdening central banks’ existing mandates. True, mandates can evolve, but these changes and institutional arrangements are very complex issues because they require building new sociopolitical equilibria, reputation and credibility. Although central banks’ mandates have evolved from time to time, these changes have taken place along with broader sociopolitical adjustments, not to replace them.