The Productivity Commission has issued a Draft Report for comment on Data Availability and Use in Australian. If the recommendations are adopted this could become a fundamental force for change, and potentially create economic momentum, and greater competition from which consumers may benefit. There is enormous untapped potential in Australia’s data.

Crucially, the proposed reforms take Australia beyond the stage of viewing data availability solely through a privacy lens, in recognition that there is much more than privacy at stake when it comes to data availability and use. Tweaking existing structures and legislation will not suffice. Rather, fundamental and systematic changes are needed to the way Australian governments, business and individuals handle data.

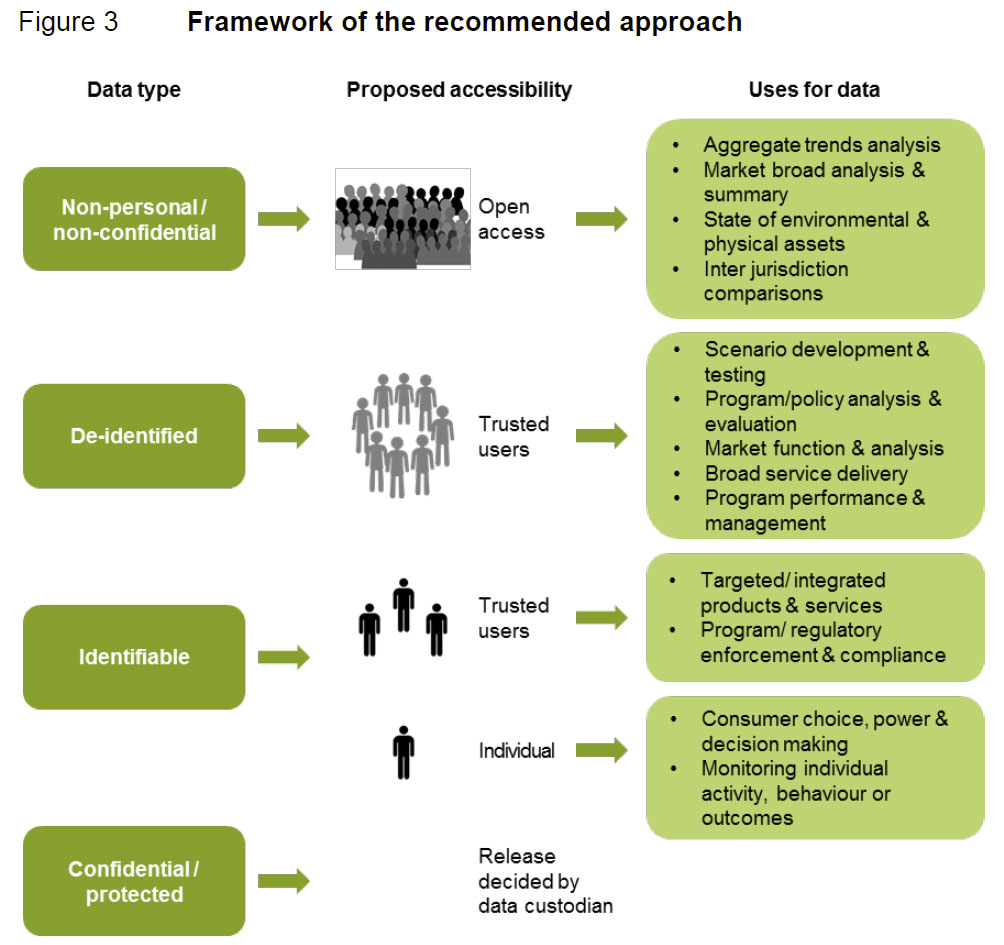

In a nutshell, data currently collected via digital transactions would remain the property of the individual (rather than the company who happened to collect it), and this data could be traded by said consumer in return for better outcomes. The report also defines a hierarchy of data types, some of which would be private, and others more widely accessible.

By way of background, the review, was requested by Scott Morrison, Treasurer, following on from the 2014 Financial System Inquiry (the Murray Inquiry) which recommended that the Government task the Commission to review the benefits and costs of increasing the availability and improving the use of data. In addition, the 2015 Harper Review of Competition Policy recommended that the Government consider ways to improve individuals’ ability to access their own data to inform consumer choices. The Government agreed to pursue these two recommendations.

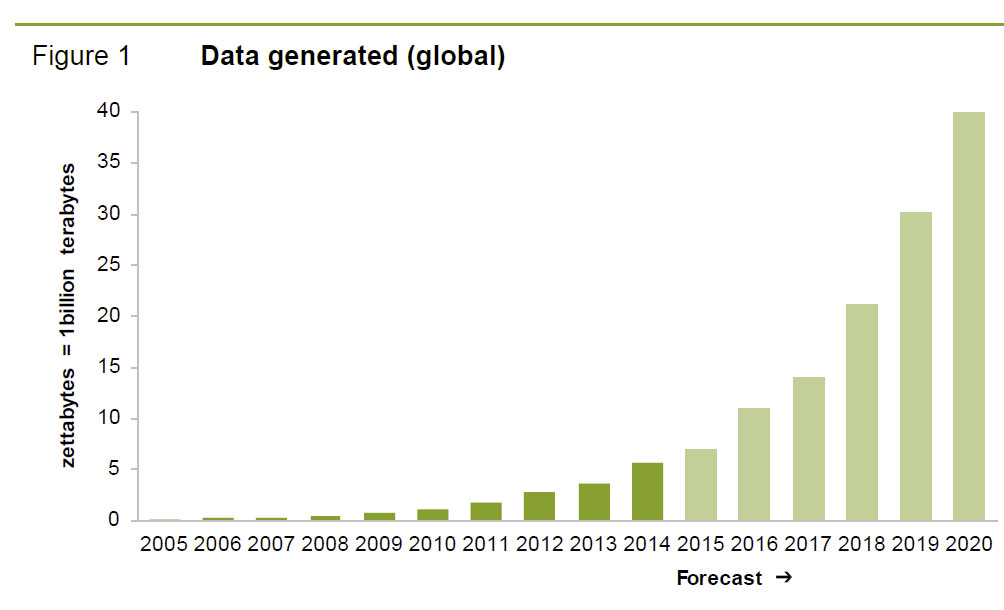

This is an important issue. On one hand, by some estimates, the amount of digital data generated globally in 2002 (five terabytes) is now generated every two days, with 90% of the world’s information generated in just the past two years.

Yet we are now only in the very nascent stage of the Internet of Things (whereby our business equipment, vehicles, appliances and wearable devices can communicate with each other and generate data), the upward trend in data generated is more likely than not to accelerate into the future.

Yet we are now only in the very nascent stage of the Internet of Things (whereby our business equipment, vehicles, appliances and wearable devices can communicate with each other and generate data), the upward trend in data generated is more likely than not to accelerate into the future.

The legal and policy frameworks under which public and private sector data is collected, stored and used (or traded) in Australia are ad hoc and not contemporary. The impetus for changes in governance structures around data — changes that deal head-on with the fact that data is increasingly digital, revealing of the activities and preferences of individual people or businesses, and held in the private sector — will not diminish. It is a global movement and, to its detriment, Australia is not participating.

Falling costs (per record) of digital data storage, and the spread of low-cost and powerful analytics tools and techniques to extract patterns, correlations and interactions from within data, are also making data analytics more usable and valuable. Yet much of the data being generated remains underutilised. Some estimate that up to 80% of data generated globally may prove to have no value (numerous duplicative digital photos, for example). But still, less than 5% of the potentially useful data is actually analysed to generate information, build knowledge, and thus inform decision making and action (EMC Corporation 2014). And some data that was previously of limited value is becoming valuable as new uses for it emerge, analytical capabilities improve, new linkages are established, or investments made to improve its quality. There is enormous untapped potential in Australia’s data.

In addition, whilst privacy is often said to be a concern, individuals still willingly and readily hand over personal information may seem a paradox. There are risks attached.

Because much of the data that is being generated is a byproduct of other activities, it was once easy for individuals to dismiss it as being of secondary importance. Today, that should not be the case. If you are using a product or service and not paying for it (or sometimes even when you are), then you are the product. This is perhaps most obvious by the ‘all or nothing’ nature of personal data requested in exchange for typically free online products and services. What you are consuming, how and when you are consuming it, is all being collected as data that is likely of more value to the supplier than whatever it is they are offering you.

Because much of the data that is being generated is a byproduct of other activities, it was once easy for individuals to dismiss it as being of secondary importance. Today, that should not be the case. If you are using a product or service and not paying for it (or sometimes even when you are), then you are the product. This is perhaps most obvious by the ‘all or nothing’ nature of personal data requested in exchange for typically free online products and services. What you are consuming, how and when you are consuming it, is all being collected as data that is likely of more value to the supplier than whatever it is they are offering you.

Here is a summary of their main points:

- Frameworks and protections developed for data collection and access prior to sweeping digitisation now need reform. This is a global phenomenon and Australia, to its detriment, is not yet participating.

- The substantive argument in favour of making data more available is that opportunities to use it are largely unknown until the data sources themselves are better known, and until data users have been able to undertake discovery of data.

- Lack of trust and numerous barriers to sharing and releasing data are stymieing the use and value of Australia’s data.

- Marginal changes to existing structures and legislation will not suffice. The Commission is proposing reforms to data availability and use, aimed at moving from a system based on risk aversion and avoidance, to one based on transparency and confidence in data processes.

- At the centre of proposed reforms is the introduction of a new Data Sharing and Release Act, a new National Data Custodian, and a suite of sectoral Accredited Release Authorities that will enable streamlined access to curated datasets.

- A key element of the recommended reforms is to provide greater control for individuals over data that is collected on them by defining a new Comprehensive Right for consumers. This right would mean consumers:

– retain the power to view information held on them, request edits or corrections, and be advised of disclosure to third parties;

– have improved rights to opt out of collection in some circumstances; and

– have a new right to a machine-readable copy of data, provided either to them or to a nominated third party, such as a new service provider. - Broad access to key National Interest Datasets should be enabled.

– For datasets designated as national interest, all restrictions to access and use contained in a variety of national and state legislation, and other program-specific policies, would be replaced by new arrangements under the Data Sharing and Release Act.

– Datasets would be maintained as national assets, access would be substantially streamlined, and linkage with other National Interest Datasets would be feasible.

– Initial datasets that may be designated national interest and publicly released could include key registries of businesses, services or assets, and data on activity and usage in areas of substantial public expenditure. - Secure sharing of identifiable data held in the public sector and by publicly funded research bodies should be formalised and streamlined. By pre-approving data uses, trusted users would have more timely access to identifiable data through Accredited Release Authorities and ethics committees.

- Reforming access to public sector data is a priority. Significant change is needed for Australia’s open government agenda to catch up with achievements in competing economies.

- The incremental costs associated with more open data access and use — including possible impacts on individuals’ privacy and willingness to share data — are expected to be minimal, but they will exist. But greater use of Australia’s data can coexist with the management of these risks, including genuine safeguards and meaningful transparency to maintain community trust and confidence.

The Commission’s recommended approach incorporates recent progress in policy and practices around data management but is deliberately aimed at creating a new, comprehensive framework that should, by design, be capable of enduring beyond current policies, personnel and institutional structures. It takes account of the significant differences in data types and associated risks and uses of each, and recognises that while the incremental risks of making data more available might appear very small (given how much data is already in the public domain), incentives and trust nevertheless have to be maintained.

As part of the review, the Commission has developed a framework for their recommended approach.

They have given considerable thought to establishing an element in the Framework to enable wider access to high value, National Interest Datasets. The intention is to promote the development of a valuable suite of datasets — some of which are released publicly; others that will be shared with a smaller group of trusted data users. Designating datasets as national interest collections will also signify their value as resources collected in the national interest, not merely (as today) for compliance, record-keeping or audit.

They have given considerable thought to establishing an element in the Framework to enable wider access to high value, National Interest Datasets. The intention is to promote the development of a valuable suite of datasets — some of which are released publicly; others that will be shared with a smaller group of trusted data users. Designating datasets as national interest collections will also signify their value as resources collected in the national interest, not merely (as today) for compliance, record-keeping or audit.

The implications for companies who possess data – like the banks – might be shocked by the implications. Expect some resistance. That said, they see to consider comprehensive credit reporting something of a special case.

In some circumstances, collating consumer data may offer net public benefit in making markets more efficient. A specific case is covered in the terms of reference for this Inquiry: comprehensive credit reporting. The Productivity Commission has previously found comprehensive credit reporting to be desirable and, consistent with the approach of New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States, a voluntary approach to data input should continue to be pursued, unless it becomes clear that a critical mass of accounts is not achievable on that basis.