Interesting speech from Kristin Forbes, External MPC Member, Bank of England “Global economic tsunamis: Coincidence, common shocks or contagion?”

She explores why countries are sometimes highly vulnerable to major events that occur outside their borders, while at other times seem fairly immune. Why do some negative events turn into global tsunamis – while others are just local ripples? Here are some extracts. The full analysis however is worth reading. It highlights the significance of markets that are more globally linked than ever before.

Consider 2 major periods of stress in the global economy: the Asian Crisis (1997-98) and the Global Financial Crisis (2008-2009).

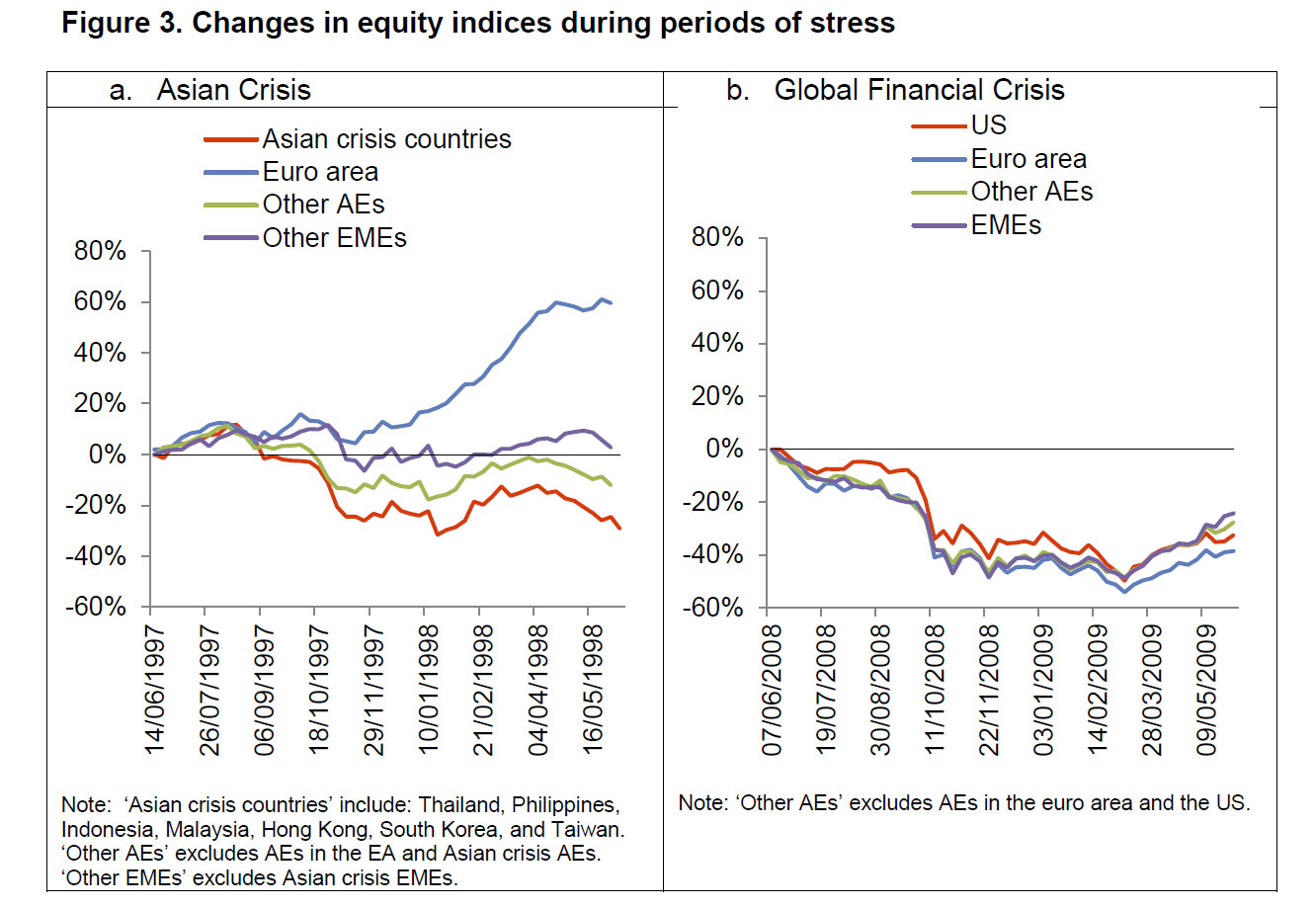

Figure 3 shows equity indices during these events for the region/country where the stress originated (in red), plus other major country groups. The Asian Crisis corresponded to sharp falls in equity indices for the Asian economies under stress (not surprisingly). These falls were mirrored (albeit to a lesser extent) in the advanced economies outside the euro area, but seemed to have minimal effect on other emerging markets. The euro area seemed immune to the Asian wave, with sharply higher – instead of lower – returns. In contrast, the Global Financial Crisis sharply affected equity indices not only in the US, but in all country groups. The equity indices for all groups are basically on top of each other for almost a year from June 2008; the Global Financial Crisis is aptly named and was clearly a global tsunami.

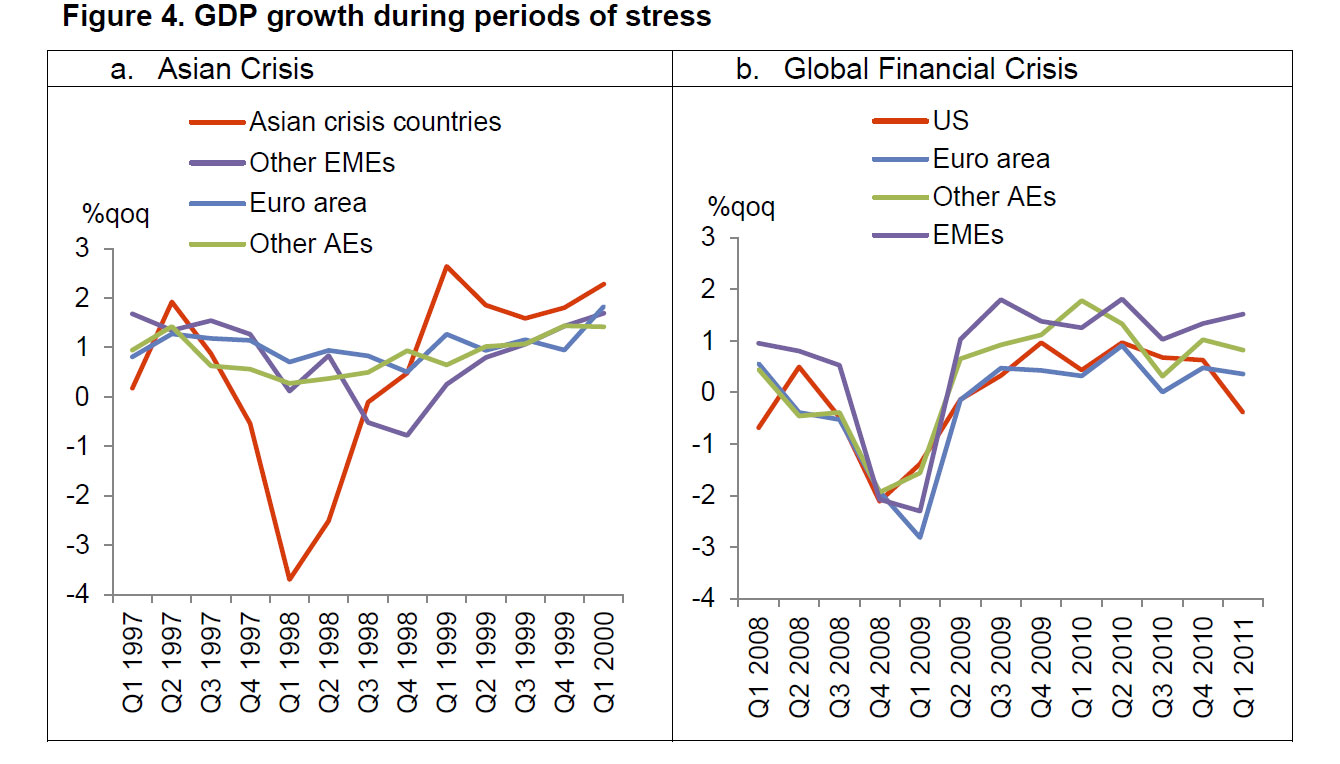

Did these disparate spillovers in equity markets correspond to similar patterns for what people in these countries care about most – real incomes and growth? Figure 4 shows GDP growth to answer this question. The Global Financial Crisis continues to merit its name – corresponding to precipitous and simultaneous declines in growth in each region, followed by simultaneous rebounds. Patterns during the Asian Crisis, however, are quite different than for equity markets. GDP growth in the advanced economies is stronger and more stable than implied by the falls in this group’s equities. GDP growth in the other emerging markets is more negatively affected than implied by the relative stability in their equity markets. And growth in the euro area is middle of the pack – showing none of the outperformance suggested by the region’s strong equity returns.

This lecture attempts to better understand these different patterns of global spillovers – especially during periods of economic stress. It addresses a number of questions. Why do economic tremors in one country sometimes evolve into devastating tsunamis in others – and sometimes fade into small ripples? When do international spillovers in financial markets also harm incomes and economic growth? How have these relationships evolved over time? And perhaps most important, how can countries create ‘tidal breaks’ against these powerful waves originating outside their borders?

The results have important implications for investors. I’ll show you that equity markets around the world move together much more closely now than in the past. This makes it more difficult for investors to diversify their portfolios and to generate returns through ‘alpha’ (differentiating oneself from average market movements). I will also provide some insights on why this has been happening and what to watch to predict when these patterns change. A common, global factor has been playing a more important role in causing markets to move together. This is affected by changes in global risk sentiment, commodity prices, and changes in US monetary policy, with events in China recently playing a more important role. Particularly striking, equity markets around the world seem to all respond in more similar ways than in the past to these global factors. It is as if they are all now sailing in the same type of boat.

This analysis also has important implications for policymakers. Policymakers are continually concerned that negative shocks originating abroad will spread to their own shores. This analysis helps understand when this concern is more likely to become a reality – and exactly what to be concerned about. It shows that sharp reactions in financial markets should be put into context. These movements certainly matter – but the international spillovers to growth and incomes tend to be much smaller than in financial markets. For policymakers concerned about supporting and stabilizing domestic incomes in the face of these external waves, this is good news. The waves emanating from abroad in financial markets can be imposing – and do have important domestic effects – but these effects on the real economy are usually more muted.

Finally, and perhaps most important, although policymakers can usually do little to stop the events that generate waves abroad, they should not despair. Certain policies can make a country more resilient. Steps such as reducing leverage and strengthening banking systems can mitigate the effects of dangerous international waves.

She concludes: There are some periods and regions where GDP growth rates do move more in sync, however, such as during the Global Financial Crisis and today in the euro area. Moreover, movements in financial markets will have important effects on incomes and growth over time, especially if they persist. When do countries become more synchronized? The analysis here suggests that common shocks play an important role, especially changes in global risk measures, global commodity prices, US monetary policy, and more recently changes in China’s economic outlook. Contagion (when the bad news originates in a specific country or countries) has also played a role, but has been less important than global events in driving the increased synchronization in equity markets over time. Perhaps most important, countries worried about the effects of these common shocks and contagion need not despair. Steps such as reducing bank leverage and strengthening financial systems appear to be powerful in terms of increasing their resilience to these adverse winds blowing from abroad.