For the first time since 1987-1988, the US credit cycle has stabilized following a surge by credit rating downgrades relative to upgrades, a jump by the high-yield default rate, and a pronounced widening by corporate bond yield spreads. After six years at 49% of US high-yield credit rating revisions from July 2009 through June 2015, downgrades soared to 71% in the year-ended June 2016. Then downgrades eased to 58% for the year-ended March 2017 and sank to 48% during Q1-2017.

The much reduced relative incidence of downgrades was joined by a drop for the forward-looking high-yield EDF (expected default frequency metric from February 2016’s current recovery high of 8.1% to a recent 3.7% and a narrowing by the high-yield bond spread from February 2016’s nearly eight-year high of 839 bp to a recent 412 bp. In addition, after peaking at January 2017’s 5.9%, the US high-yield default rate has eased to March’s 4.7% and is projected to average 3.1% during 2017’s final quarter.

Market expects profits to again outpace corporate debt

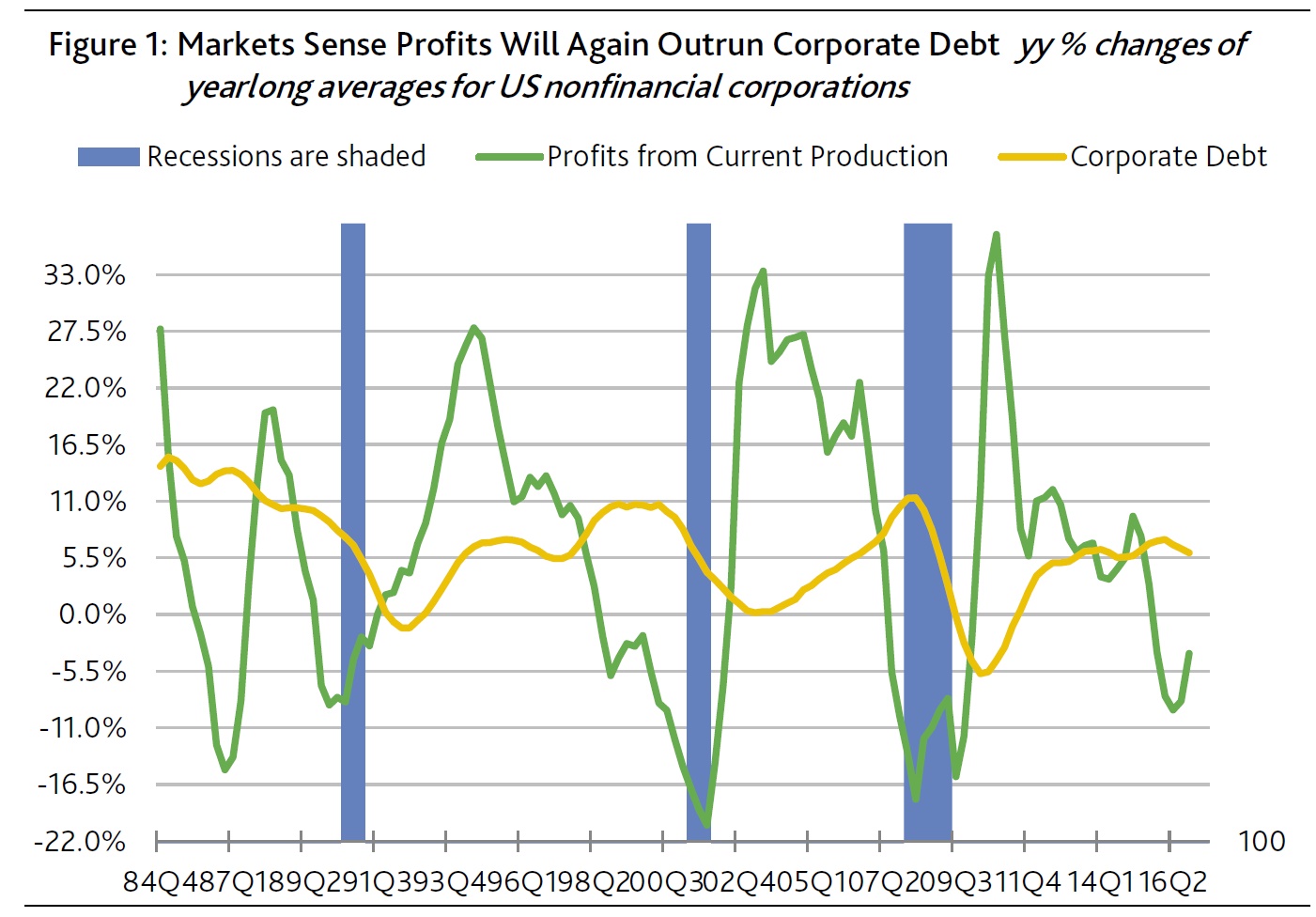

The deterioration of high-yield credit rating revisions comparing the six years ended June 2015 with the year ended June 2016 was linked to a dramatically different performance by nonfinancial-corporate profits from current production. After having advanced by 9.8% annually, on average, during the six years ended June 2015, profits from current production contracted by -9.2% annually during the year ended June 2016. The loss of financial flexibility to the shrinkage of profits was made worse by an acceleration of nonfinancial-corporate debt from the 2.5% average annualized rise of the six-years-ended June 2015 to the 6.8% year-over-year increase of the following 12 months. (Figure 1.)

Few broad-based trends weaken corporate credit quality more than the simultaneous contraction of earnings and expansion of debt. To the contrary, the faster growth of profits vis-a-vis debt typically lessens default risk significantly.

Fourth-quarter 2016 showed a narrowing of debt’s faster expansion vis-a-vis profits. For the first time since Q1-2015’s year-to-year increase of 12.0%, Q1-2017’s profits from current production managed to grow from a year earlier by 3.0%. Previously, this measure of profits had contracted annually in each of the six quarters ended Q3-2016 by -7.0%, on average, which had been joined by an accompanying 6.8% average yearly increase for corporate debt. Though Q4-2016’s 5.2% annual increase by corporate debt still outran profits’ 3.0% rise, at least it occurred in the context of profits growth, as well as slowing noticeably from when profits shrank.

Credit often gets pummeled when profits shrink while debt grows

The last two times a year-long contraction by profits was accompanied by an acceleration of corporate debt, the imbalance eventually inflicted heavy damage on corporate credit. The two earlier episodes commenced in Q2-2007 and Q1-1998.

Ultimately, corporate bond yield spreads ballooned and the high-yield default rate climbed sharply higher. The high-yield bond spread swelled from the 283 bp of Q2-2007 and the 338 bp of Q1-1998 to cycle highs of 1,678 bp for Q4-2008 and 971 bp for Q4-2002. In addition, the default rate soared from Q2-2007’s 1.5% and Q1-1998’s 2.5% to cycle highs of 14.5% for Q4-2009 and 10.9% for Q1-2002.

Credit survived mid-1980s drop by profits amid rapid debt growth

However, when corporate debt’s moving year-long average outran comparably measured profits beginning with Q2-1985 and ending in Q3-1987, both spread widening and the climb by the default rate were much more limited compared to 2007 and 1998. Better yet, unlike 1998 and 2007, 1986’s simultaneous contraction of profits and expansion of debt did not eventually lead to a recession.

Markets now sense that the 2015-2016 bout of brisk debt growth amid shrinking profits will mimic what transpired in the mid-1980s and, thus, will be succeeded by a profits recovery that outpaces corporate debt. That is exactly what occurred from Q4-1987 through Q4-1988, when profits’ 15.0% annualized advance well outran the still lively 10.3% annualized growth of corporate debt.

Nevertheless, the 1987-1988 reprieve was short lived. By year-long 1989, the unfavorable imbalance returned, as profits contracted by -6.9% annually while corporate debt grew by +9.6%.

The experience of the mid- to late-1980s warns against becoming too optimistic if, as the market implicitly expects, profits again outrun debt by late 2017. By itself, the current upturn’s maturity suggests that pent-up demand has been mostly depleted. For example, despite the most attractive auto sales incentives since 2009, unit sales of light motor vehicles fell from a year earlier in 2017’s first quarter. Elsewhere, a growing number of retail chains struggle with lower than expected sales.

The pace of home sales during housing’s peak selling season of March through June will provide critical insight regarding the health of domestic expenditures. If home sales unexpectedly stall, profits may be incapable of outpacing corporate debt, which would widen spreads significantly and worsen the now benign outlook for defaults. Comparably to what transpired in the 1980s, corporate credit’s current reprieve may not last much longer than a year. And that would be especially true if short- and long-term interest rates rose to heights that are too burdensome for financial markets and business activity.

High-yield downgrades eclipse upgrades when focusing on fundamentals

The US high-yield credit rating revisions of 2017’s first quarter showed the most upgrades relative to downgrades since 2014’s third quarter. A preliminary count revealed 89 upgrades and 83 downgrades. However, the accompanying revisions of investment-grade ratings showed three more downgrades (17) than upgrades (14).It is important to note that not all rating revisions are the consequence of changed fundamentals. For example, some rating revisions stem from changes in creditor protection owing to the issuance of new debt. Other revisions not viewed as fundamentally driven include stand-alone special-events such as mergers, acquisitions, divestitures, equity buybacks, special dividends, and infusions of common equity capital.

Whenever fundamentals and special events simultaneously trigger a rating revision, the rating change is tallied as driven by fundamentals. Only when the influence of fundamentals is viewed as negligible is the revision deemed to be for some other reason.

Recognizing the impossibility of establishing unequivocally that a rating change was due only to fundamentals, fundamentals appear to have been responsible for 54 of Q1-2017’s high-yield upgrades and 59 of the high-yield downgrades. Thus, when considering only rating changes caused by fundamental drivers, Q1-2017 was home to more high-yield downgrades than upgrades.

The first-quarter 2017 upgrade share of high-yield credit rating changes fell from 52% to 48% after limiting the sample to fundamentally-driven revisions. Fundamentals last figured in more high-yield upgrades than downgrades in 2014’s third quarter, or when non-financial corporations posted lively year-to-year advances of 5.8% for gross-value-added and 11.3% for profits from current production, as the high-yield spread averaged a thin 376 bp.

Comparable revenue and earnings results for 2017’s first quarter are not yet available, though the consensus looks for implied year-long 2017 gains of 4.3% for gross-value-added and 5.0% for pretax operating profits. First-quarter 2017’s high-yield bond spread of 397 bp was much thinner than the 477 bp of Q4-2016, or when upgrades’ share of high-yield rating changes fell from 32% overall to just 27% when limited to fundamentals.

A switch to the opposite direction held for investment-grade revisions, too, where the 11 upgrades led the eight downgrades when limiting the sample to fundamentally driven rating changes. Mergers and acquisitions (M&A) figured in nine of the 17 investment-grade downgrades, but entered into fewer three of the group’s 14 upgrades.

No longer do the problems of the oil & gas industry skew the number of downgrades higher. In Q1-2017, the oil & gas industry figured in 12 upgrades and 12 downgrades — 11 apiece for high-yield and one each for investment grade. Ample liquidity and firmer energy prices account for why the frequency of oil & gas-related high-yield rating revisions improved from the per quarter averages of four upgrades and 57 downgrades from the year-ended June 2016.

Recent high-yield spread implies the market expects more upgrades than downgrades

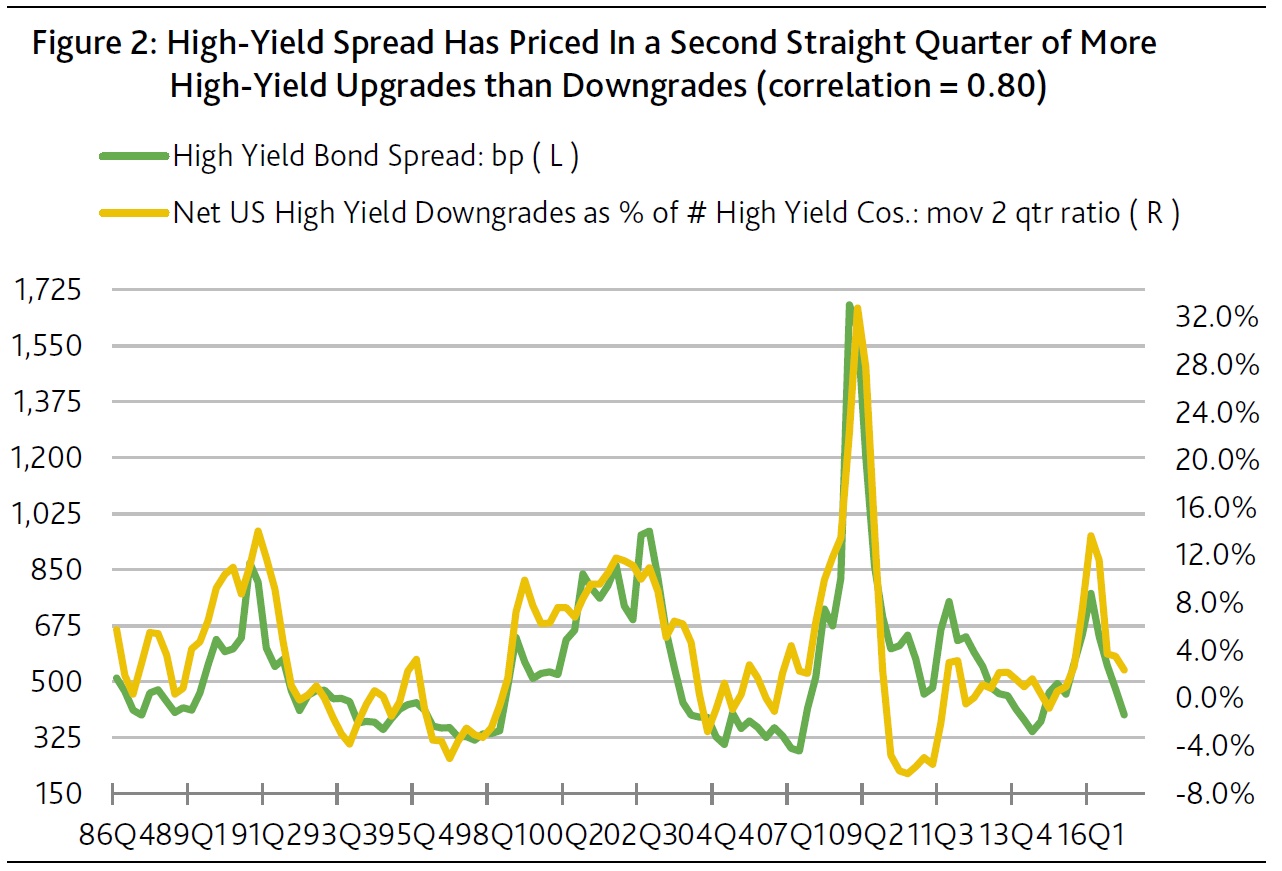

As derived from a sample that commences with 1986’s final quarter, the quarter-long average of the US high-yield bond spread generates a relatively strong correlation of 0.80 with the moving two-quarter ratio of net high-yield downgrades as a percent of the number of high-yield issuers. Net high-yield downgrades, or the difference between the number of downgrades less upgrades, fell from Q4-2016’s +53 to Q1-2017’s -6. In turn, the moving two-quarter ratio of net high-yield downgrades dipped from Q4-2016’s 3.6% to Q1-2017’s 2.4% of the number of high-yield issuers.

The narrowing of the high-yield bond spread from the 551 bp of Q4-2016 to Q1-2017’s 477 bp was qualitatively consistent with the accompanying drop by the relative incidence of net downgrades. First-quarter 2017’s moving two-quarter net downgrade ratio was the lowest since the 1.0% of 2015’s second quarter, or when the high-yield spread averaged 462 bp. When the net downgrade ratio last peaked at Q1-2016’s 13.7%, the high-yield spread averaged a very wide 776 bp. (Figure 2.)

If high-yield downgrades equal upgrades over a two-quarter span, the long-term statistical relationship predicts a midpoint of 436 bp for the high-yield bond spread. Thus, the recent high-yield spread of 412 bp implicitly expects that upgrades will outnumber downgrades for a second straight quarter in Q2-2017.