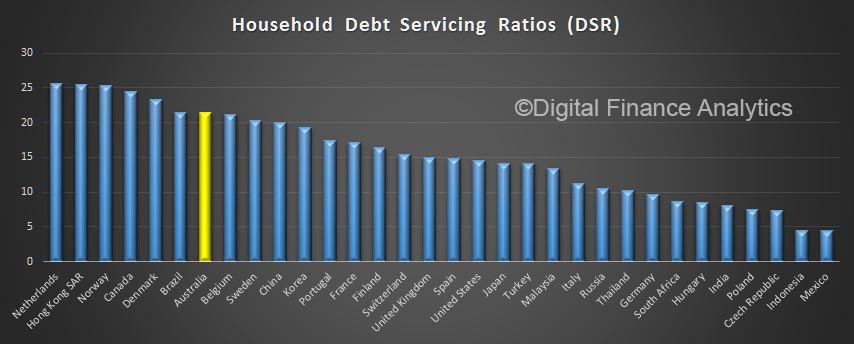

The BIS has released the latest DSR data for major economies. Australia sits firmly near the top, alongside Norway, Netherlands, Canada and Hong Kong. USA and UK are significantly lower.

The DSR reflects the share of income used to service debt and has been found to provide important information about financial-real interactions. For one, the DSR is a reliable early warning indicator for systemic banking crises. Furthermore, a high DSR has a strong negative impact on consumption and investment. The DSRs are constructed based primarily on data from the national accounts. You can read more about the index here.

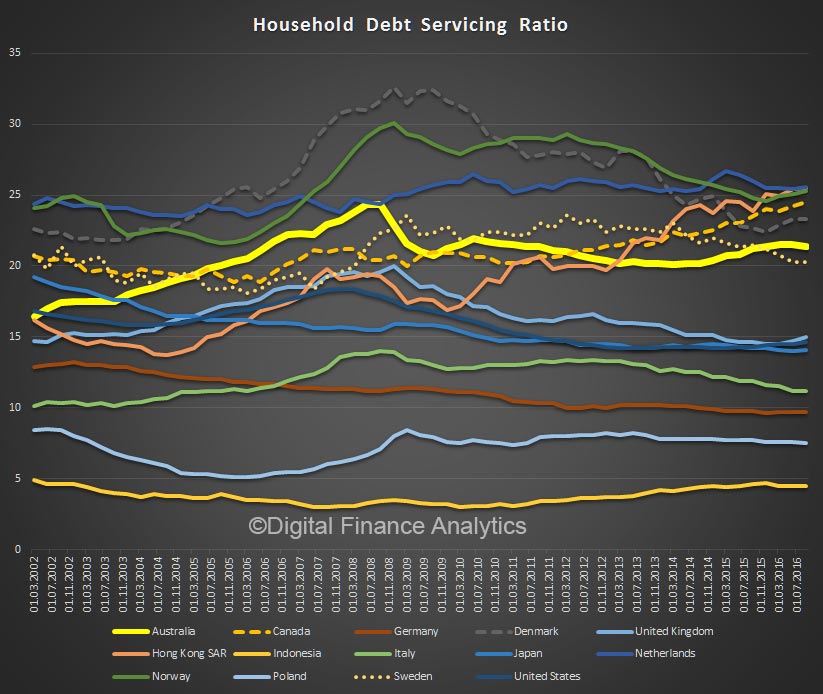

Here are comparative charts to September 2016.

The trends over time are also interesting, as interest rates and debt levels change. I have removed a few countries to make the chart easier to read.

The trends over time are also interesting, as interest rates and debt levels change. I have removed a few countries to make the chart easier to read.

Debt forms a central part of the narrative of financial crises and financial cycles more generally. Leverage, often proxied at the aggregate level by the ratio of the stock of liabilities (ie debt) to income, has received much attention as an indicator of financial excesses and vulnerabilities. Less discussed, but equally important, is the debt service ratio (DSR), which captures the share of income used for interest payments and amortisations. These debt-related flows are a direct result of previous borrowing decisions and often move slowly as they depend on the duration and other terms of credit contracts. They have a direct impact on borrowers’ budget constraints and thus affect spending.

Since the DSR captures the link between debt-related payments and spending, it is a crucial variable for understanding the interactions between debt and the real economy. For instance, during financial booms, increases in asset prices boost the value of collateral, making borrowing easier. But more debt means higher debt service ratios, especially if interest rates rise. This constrains spending, which offsets the boost from new lending, and the boom runs out of steam at some point. After a financial bust, it takes time for debt service ratios, and thus spending, to normalise even if interest rates fall, as principal still needs to be paid down. In fact, the evolution of debt service burdens can explain the dynamics of US spending in the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis fairly well. In addition, DSRs are also highly reliable early warning indicators of systemic banking crises.