The link between jobs and economic growth is not always a straight line for countries, but that doesn’t mean it’s broken.

Economists track the relationship between jobs and growth using Okun’s Law, which says that higher growth leads to lower unemployment.

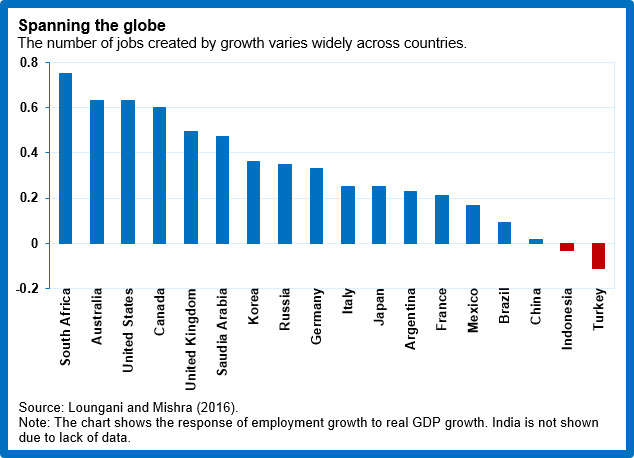

New research from the IMF looks at Okun’s Law and asks, based on the evidence, will growth create jobs? The findings show a striking variation across countries in how employment responds to GDP growth over the course of a year.

In some countries, when growth picks up, employment goes up and unemployment falls; in other countries the response is quite muted. A pick-up in growth—through a stimulus to the demand side of the economy, for instance increased government spending on infrastructure—will result in more jobs.

Some countries generate more jobs from growth than others

The extent of job creation in the short run varies across countries. This chart shows how much employment increases when growth picks for the Group of Twenty advanced and emerging economies, which together account for the lion’s share of global GDP and employment.

While Okun’s Law holds overall for the United States, the relationship between unemployment and growth since 2011 did deviate from the historical pattern because the depth and duration of the great recession—the period following the global crisis in 2008—led to so many more people losing their jobs.

In South Africa, Australia, and Canada, a 1 percent increase in GDP is matched by an increase in employment of 0.6 percent or higher. In contrast, there is virtually no response of employment to growth in China, Indonesia, and Turkey.

The extent to which changes in growth account for changes in unemployment and employment also varies across countries. GDP growth accounts for over 70 percent of the variation in employment in Canada and the United States, about 40 percent in Russia, the United Kingdom, and Australia, and very little in many other countries.

For the majority of countries around the world, taking account of growth is an important part of understanding short-run changes in unemployment. For other countries, there are several possible explanations for the weakness of the jobs-growth link. In some cases, reported unemployment rates may not fully reflect the true unemployment rate. Some countries are going through rapid structural change and unemployment may be driven by this longer-run trend rather than short-run fluctuations.

You can’t have one without the other

This then begs the questions: Where will growth come from? Global growth has been too low, for too long, and for too few. The answer is found on both the demand and supply side of the economy.

For example, if companies do not see their sales improving, they will not increase their capacity to produce more, so it is essential to ensure that the demand is there to sustain supply. But without supply measures, gains in output based solely on a stimulus to demand will prove temporary. The range of supply measures varies, from removing bottlenecks in the power sector to reforms in labor and product markets. In many countries, there is a strong case to increase spending on public infrastructure, which would provide a much-needed boost to demand in the short term and would also help supply.

All this means countries need to use all policies—monetary, fiscal, and structural—to maximize growth within countries and amplify the impact though coordination across countries.

This “three-pronged” approach would free up more policy space—more room to act—than is commonly assumed.