The Reserve Bank of New Zealand just published an interesting report on this important topic. High and rapidly rising levels of household debt can be risky. A high level of debt increases the sensitivity of households to any shock to their income or balance sheet. And during periods of financial stress, highly indebted households tend to cut their spending more than their less-indebted peers. This can amplify a downturn and helps to explain why many advanced economies since the 2008-09 crisis have had subdued recoveries. Financial institutions can suffer direct losses from lending to households, although these losses are rarely enough on their own to cause a systemic banking crisis. The sustainability of household debt can be assessed best by looking at data detailed enough to build a picture of how debt and debt servicing capacity is distributed across different types of borrowers.

Households, either individually, or in aggregate, can ‘over-borrow’, and financial institutions can ‘over-lend’ to them. A high level of household debt can affect both the financial system and the economy in several ways that are explained in this article.

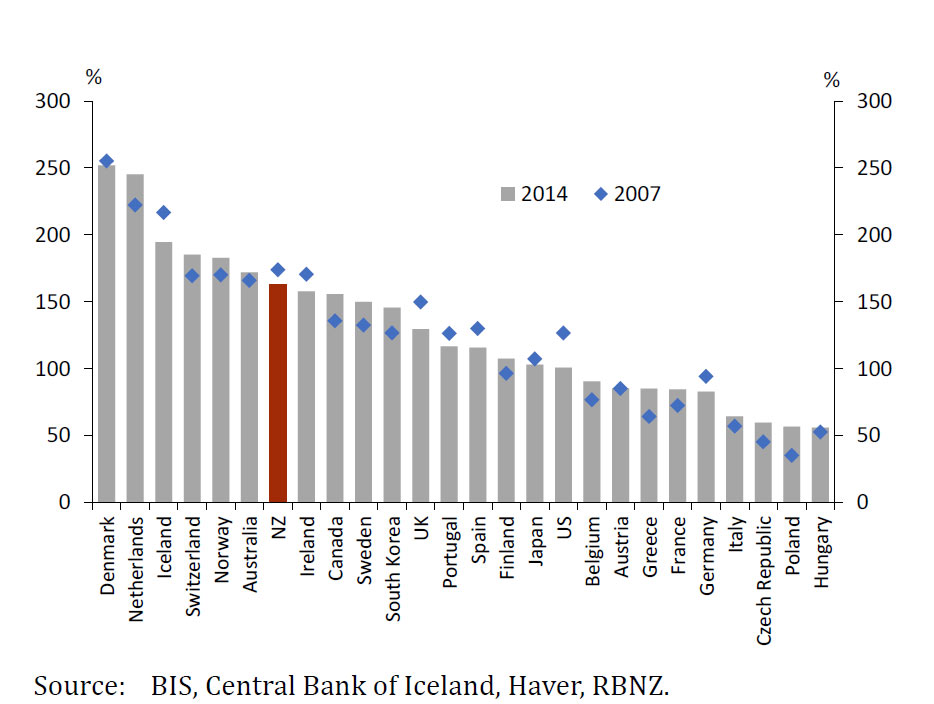

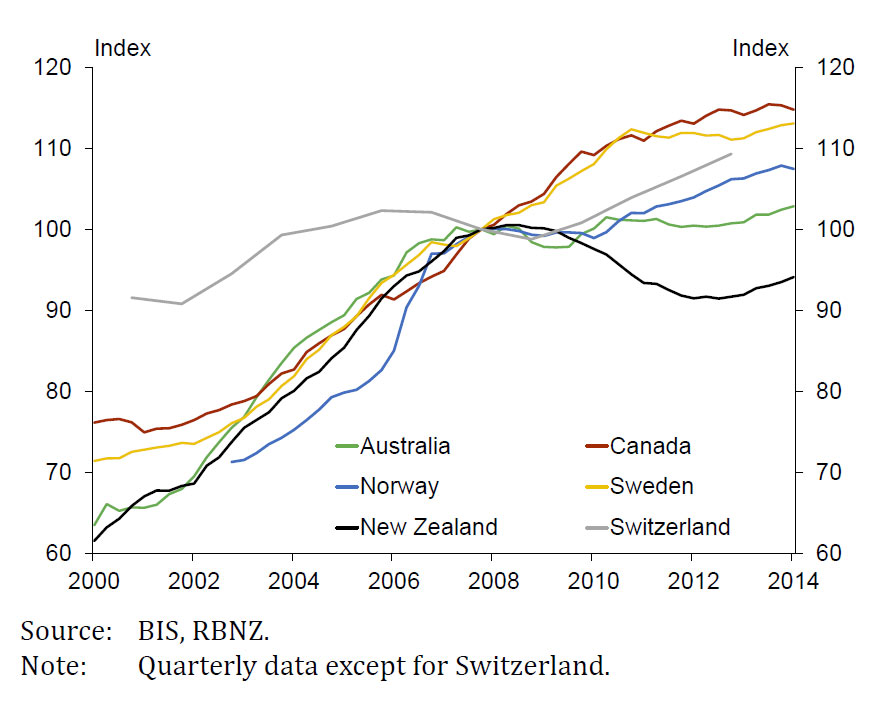

Two sets of comparative data makes interesting reading. First, household debt-to-disposable income ratio – by country. Cross-country comparisons of debt levels need to be treated with caution, given a variety of measurement issues and different institutional features. That said, the rise in household debt in New Zealand over the last cycle was not exceptional compared to other countries, and Australia is higher. Second, Household debt-to-income ratios – selected countries. The Reserve Bank comments that “in quite a few countries there was no domestic financial crisis and little sustained fall in house prices. Policymakers in several of these economies, including New Zealand, have subsequently become concerned by household sector developments over the past several years – developments underpinned by low interest rates and an easing in lending standards. Household debt levels have started to increase from already high levels, while house prices are growing from a starting point of ‘over-valuation’.

Second, Household debt-to-income ratios – selected countries. The Reserve Bank comments that “in quite a few countries there was no domestic financial crisis and little sustained fall in house prices. Policymakers in several of these economies, including New Zealand, have subsequently become concerned by household sector developments over the past several years – developments underpinned by low interest rates and an easing in lending standards. Household debt levels have started to increase from already high levels, while house prices are growing from a starting point of ‘over-valuation’.

The implementation of an LVR speed limit in New Zealand reflected emerging developments in the housing market that if left unchecked, could have threatened future macroeconomic stability. Some other jurisdictions have also used new macro-prudential tools, in combination with improving the existing underlying prudential framework. In addition to LVR restrictions, other measures include: maximum debt servicing-to-income limits, maximum debt to-income limits, higher risk weights on banks’ housing loans and prudent (or responsible) lending guidelines.

The implementation of an LVR speed limit in New Zealand reflected emerging developments in the housing market that if left unchecked, could have threatened future macroeconomic stability. Some other jurisdictions have also used new macro-prudential tools, in combination with improving the existing underlying prudential framework. In addition to LVR restrictions, other measures include: maximum debt servicing-to-income limits, maximum debt to-income limits, higher risk weights on banks’ housing loans and prudent (or responsible) lending guidelines.

They conclude that:

“This article has focused on the various channels through which household debt can affect the financial system and broader economy. In this sense, households can ‘over-borrow’, although this is often not apparent in ‘real time’ and excess debt levels can lead to, or aggravate, economic downturns or periods of financial distress. The relationship between household indebtedness and consumption volatility is important for the macroeconomy, because it means that the behaviour of highly indebted households during periods of financial duress can amplify downturns. While historical evidence suggests losses on household lending are rarely the sole factor in systemic banking crises, housing-related credit booms and busts often occur alongside booms and busts in other sectors such as the (much riskier) construction and commercial property sector. It is also worth noting that, over time, housing loan portfolios have become a larger share of bank lending in many countries, including New Zealand, increasing their potential to play a larger part in future financial crises. Thus household debt is an important area of focus from a financial stability perspective.

Good micro-level household data provide an important window into how debt and debt servicing capacity is distributed across the household sector, and are also helpful for carrying out simple stress-tests of the sector using a range of large, but plausible shocks. New Zealand’s data in this area are improving. Data from the Household Economic Survey show a rise in the proportion of borrowers with a high LVR and high debt-to-income ratio, thereby supporting the view that LVR speed limits have been appropriate to curtail risks to financial stability. The Reserve Bank will continue to develop its framework for analysing household sector risk and vulnerabilities.”