And so it starts. The latest musings from Australian’s army of economists are beginning to wake up to the grim reality. Reality is not friendly. And the news will likely get worse ahead.

First, Westpac says that the unemployment rate is set to reach 11% by June. The economy is now expected to contract by 3.5% in the June quarter. And a sustained recovery is not expected until Q4.

Just last week they forecast a peak in the unemployment rate of 7%. Since then we got more extensive shutdowns than originally envisaged. Economic disruptions are set to be larger as the government moves to address the enormous health challenge which the nation now faces.

They says that historically, recessions have tended to emanate from investment cycles, particularly those centred on property and building with the initial shock centred on construction. As this recession will hit services much harder, the loss in jobs will be much quicker, but so too can the rebound be much faster, all dependent on how many firms remain solvent.

In usual recessions it is often uncertain whether the economy is in recovery phase whereas the signals around government policy (particularly shutdowns) will be much clearer and households and business will respond.

Their latest forecasts are based on an assessment of the expected impact of the Package on jobs and growth.The two stimulus packages cost a total of $25.8bn in 2019/20 and $36.3bn in 2020/2021.Of that total of $62bn, $22.85bn is allocated to direct payments to the unemployed and social security beneficiaries while $31.9bn is set aside for small business to retain workers.

However small business only receive cash if they retain workers. The subsidy (keeping cash which is withheld from workers for PAYE tax) is only, say, 20–30% of the direct cost of the worker. Given the current hugely challenging outlook for business, the Package will be measured in terms of its success in keeping people in work.

And AMP’s Shane Oliver says:

Auction clearance rates and sales momentum are showing some signs of slowing this month. This may reflect an increasing desire on the part of buyers and sellers to put property transactions on hold to avoid being exposed to the virus unnecessarily. Social distancing policies will only intensify this. On its own this may crash transactions but may just flatten price gains.

However, it’s the likely recession that we have now entered due to coronavirus related shutdowns that imposes the big risk. We expect at least two negative quarters of GDP growth in the March and June quarters with the risk that the September quarter is also negative. And the contraction could be deep because big chunks of the economy will be largely shut – tourism, travel, and entertainment with a severe flow on to parts of retailing. The toilet paper, sanitiser and canned/frozen food boom may help supermarkets for a while – but as Deutsche Bank recently calculated for every $1 spent on such items there is $15 spent on things that are vulnerable to social distancing.

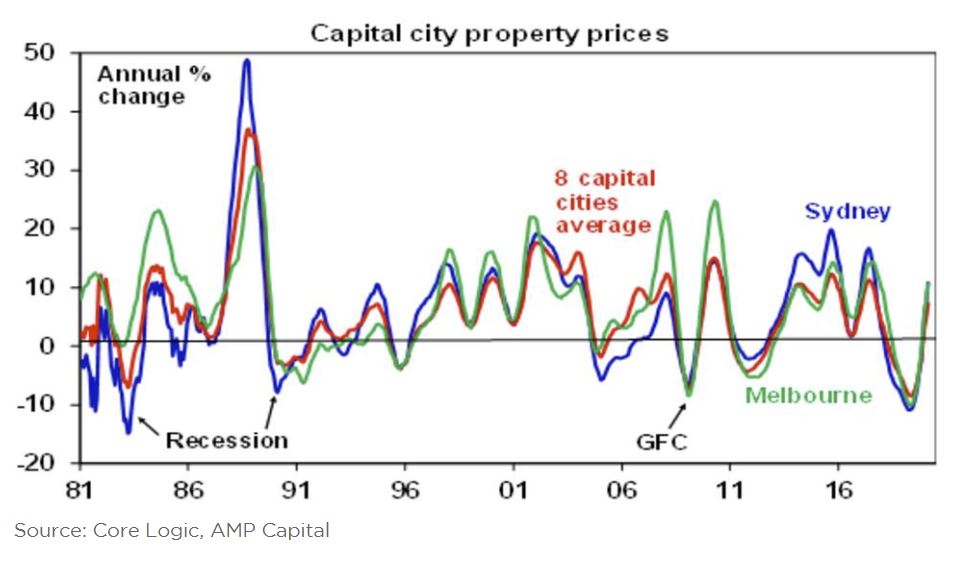

Past large share market falls have seen a mixed impact on property prices. The 1987 50% share market crash actually boosted home prices as investors switched from shares to property. But the key is what happens to unemployment as this often forces sales and crimps demand. Back in 1987 the economy remained strong and unemployment fell but the recessions of the early 1980s and early 1990s saw falls in average national capital city home prices of 8.7% and 6.2% respectively as unemployment rose. The GFC share market fall of 55% also saw a 7.6% home price fall, even though it wasn’t a recession, because unemployment rose from 4% to nearly 6%.

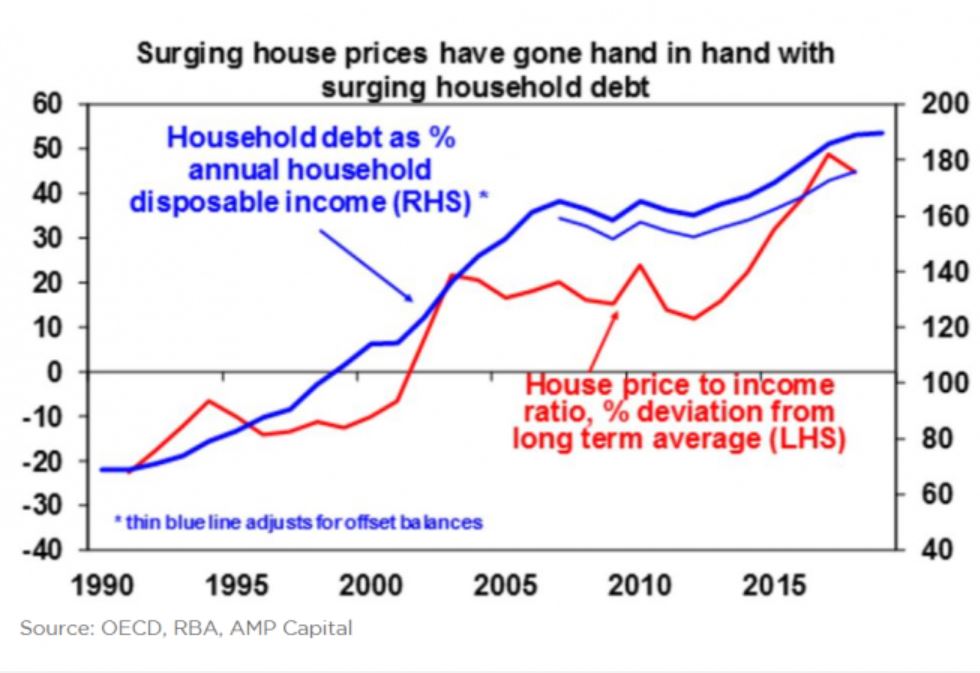

If the recession turns out to be long – pushing unemployment to say 10% or more – then this risks tripping up the underlying vulnerability of the Australian housing market flowing from high household debt levels and high house prices. The surge in prices relative to incomes (and rents) over the last two decades has gone hand in hand with a surge in household debt relative to income that has taken Australia from the low end of OECD countries to the high end.

So he says “we have always concluded that the combination of high prices and debt on their own won’t trigger a major crash in prices unless there are much higher interest rates or a recession. Unfortunately, we are now facing down the barrel of the latter. A sharp rise in unemployment to say 10% or beyond risks resulting in a spike in debt servicing problems, forced sales and sharply falling prices. This could then feedback to weaken the broader economy as falling home prices lead to less spending and a further rise in unemployment and more defaults and so on. This scenario could see prices fall 20% or so”.

Bear in mind though that part of this would just be a reversal of the 9% bounce in average capital city prices seen since mid-last year.

It’s also not our base case but it highlights why governments and the RBA really have to work hard to avoid letting the virus cause a lot of company failures, surging unemployment and household defaults.

And Goldman Sachs is still relatively sanguine.

Goldman Sachs said it was now forecasting a 6 per cent contraction in the domestic economy in 2020 — the biggest since the 1920s Great Depression — with unemployment peaking at 8.5 per cent.

On the upside, the strength of Australian bank balance sheets in terms of funding, liquidity and capital left them “significantly less vulnerable than compared to any point in the recent past”.

“Similarly, the source of historic loan losses for banks — corporate balance sheets — enter this downturn in a better condition than at any point in the last 40 years, with close to all-time-low levels of gearing and all-time low debt-servicing ratios,” Goldman said.

But given the scale of the forecast contraction, bad debts were now expected to rise significantly to 50bps of loans and slash bank earnings by 20 per cent.

A hard-landing scenario would wipe out between 50-70 per cent of the sector’s earnings.