According to the latest from The St.Louis Fed On The Economy Blog, individuals who were in financial distress five years ago were about twice as likely to be in financial distress today when compared with an average individual.

Many households have experienced financial distress at least one time in their life. In these situations, households miss payments for different reasons (unemployment, sickness, etc.) and eventually file bankruptcy to discharge those obligations.

In a recent working paper, I (Juan) and my co-authors Kartik Athreya and José Mustre-del-Río argued that financial distress is not only quite widespread but is also very persistent. Using Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel/Equifax data, we reported that individuals who were in financial distress five years ago were about twice as likely to be in financial distress today when compared with an average individual.1

Consumer Bankruptcy

In this post, we focus our attention on a very extreme form of financial distress: consumer bankruptcy. We obtained financial distress data from the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF), conducted by the Board of Governors. The data span from 1998 to 2016 with triennial frequency, and the respondents who are younger than 25 or older than 65 have been trimmed.2

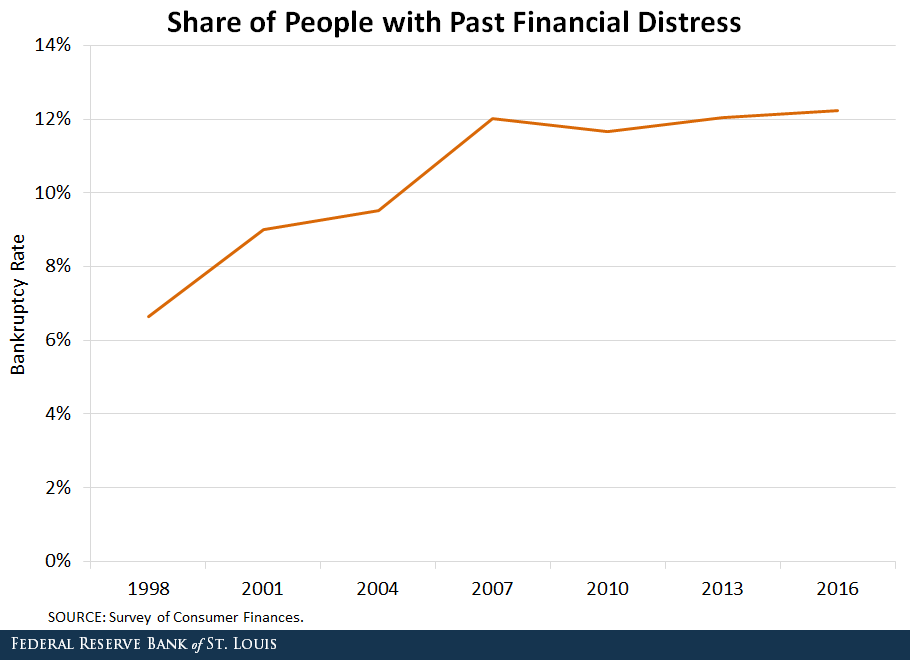

We first measured the share of households that had previously experienced an episode of financial distress by looking at people who filed for bankruptcy five or more years ago.3 The figure below shows that the share of households with past financial distress increased from approximately 6.6 percent in 1998 to 12.2 percent in 2016.

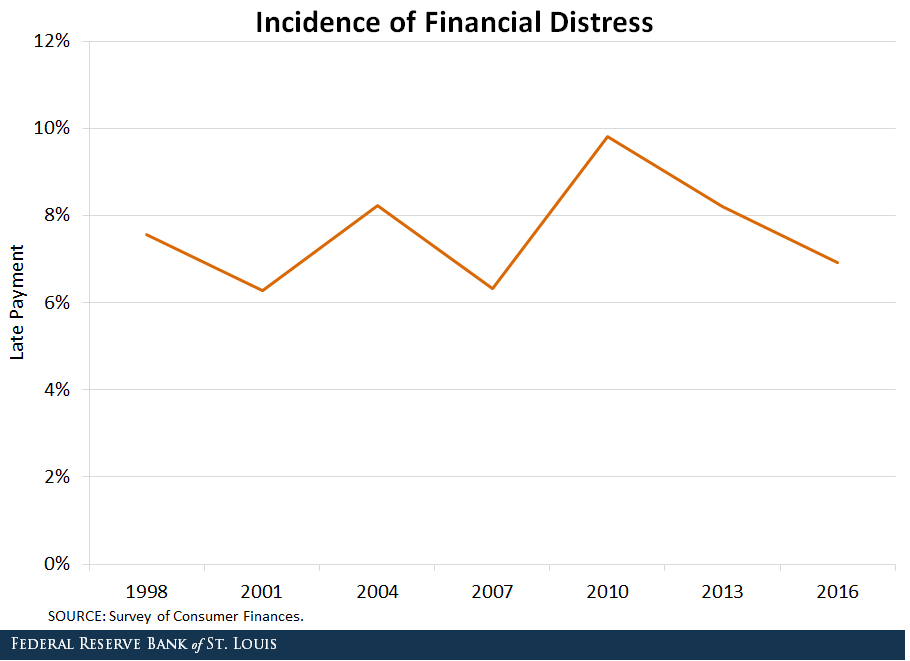

We then measured current financial distress by computing the share of households that delayed their loan payment on the year the survey was conducted.4 (We recognize that this measure is less extreme, as only a share of households that are late making payments will end up in bankruptcy.)5

The figure below shows that while there are minor fluctuations in the share of households with late payments throughout the sample period, the numbers remained around 8 percent.

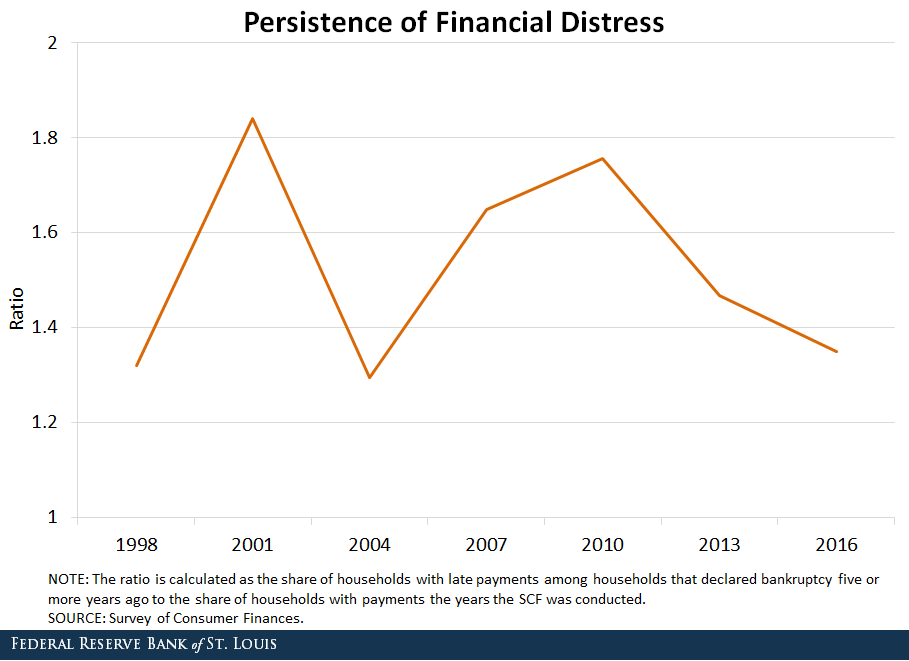

Finally, we created a ratio to measure the persistence of financial distress. It compares the share of households with late payments among households that declared bankruptcy five or more years ago to the share of households with late payments the year the SCF was conducted.

If financial distress was not persistent at all, both shares would be equal, and the ratio would be one. Thus, a value greater than one indicates the persistence of financial distress. The figure below shows the evolution of the persistence of financial distress over the years.

The ratio fluctuates around 1.5, implying that the households that have encountered an episode of financial distress in the past are 1.5 times more likely to delay payment today, compared to average households.