Monetary policy is alive and well, according to the FED, and interest rate rises are on the cards in the US. Chair Janet L. Yellen spoke at “Designing Resilient Monetary Policy Frameworks for the Future,” a symposium sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Jackson Hole, Wyoming, her speech was entitled “The Federal Reserve’s Monetary Policy Toolkit: Past, Present, and Future.”

The AU/US dollar moved in reaction to the speech.

In a nutshell, monetary policy remains relevant, and given the current economic indicators, there appears scope for rate rises later this year, possibly as soon as September. Her comments on how rate adjustments have been simulated are worth reading. It also means that we may see some falls in asset prices as the rises bite, across stocks and property.

In a nutshell, monetary policy remains relevant, and given the current economic indicators, there appears scope for rate rises later this year, possibly as soon as September. Her comments on how rate adjustments have been simulated are worth reading. It also means that we may see some falls in asset prices as the rises bite, across stocks and property.

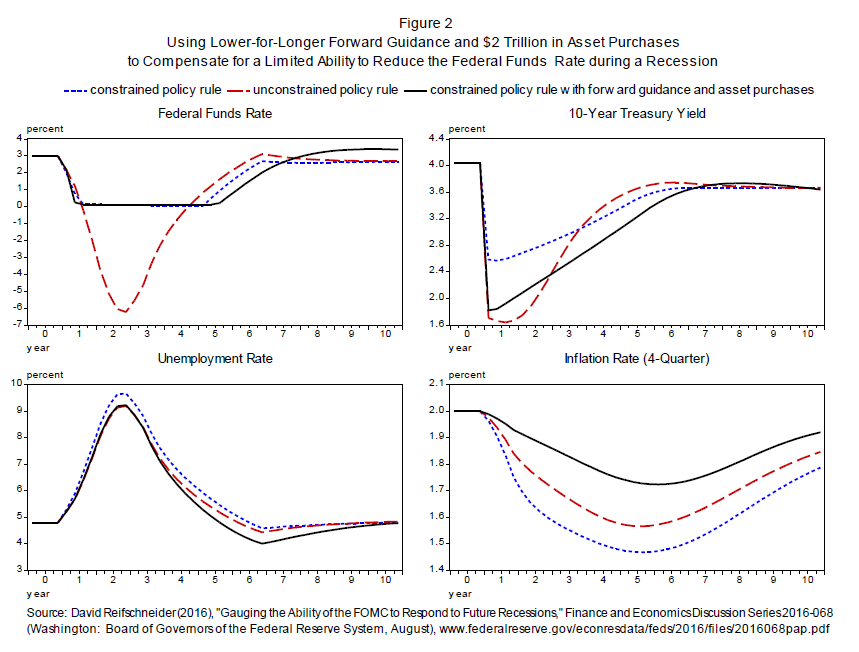

A recent paper takes a different approach to assessing the FOMC’s ability to respond to future recessions by using simulations of the FRB/US model. This analysis begins by asking how the economy would respond to a set of highly adverse shocks if policymakers followed a fairly aggressive policy rule, hypothetically assuming that they can cut the federal funds rate without limit. It then imposes the zero lower bound and asks whether some combination of forward guidance and asset purchases would be sufficient to generate economic conditions at least as good as those that occur under the hypothetical unconstrained policy. In general, the study concludes that, even if the average level of the federal funds rate in the future is only 3 percent, these new tools should be sufficient unless the recession were to be unusually severe and persistent. Figure 2 in your handout illustrates this point.

It shows simulated paths for interest rates, the unemployment rate, and inflation under three different monetary policy responses–the aggressive rule in the absence of the zero lower bound constraint, the constrained aggressive rule, and the constrained aggressive rule combined with $2 trillion in asset purchases and guidance that the federal funds rate will depart from the rule by staying lower for longer. As the blue dashed line shows, the federal funds rate would fall far below zero if policy were unconstrained, thereby causing long-term interest rates to fall sharply. But despite the lower bound, asset purchases and forward guidance can push long-term interest rates even lower on average than in the unconstrained case (especially when adjusted for inflation) by reducing term premiums and increasing the downward pressure on the expected average value of future short-term interest rates. Thus, the use of such tools could result in even better outcomes for unemployment and inflation on average.

Of course, this analysis could be too optimistic. For one, the FRB/US simulations may overstate the effectiveness of forward guidance and asset purchases, particularly in an environment where long-term interest rates are also likely to be unusually low.22 In addition, policymakers could have less ability to cut short-term interest rates in the future than the simulations assume. By some calculations, the real neutral rate is currently close to zero, and it could remain at this low level if we were to continue to see slow productivity growth and high global saving.23 If so, then the average level of the nominal federal funds rate down the road might turn out to be only 2 percent, implying that asset purchases and forward guidance might have to be pushed to extremes to compensate.24 Moreover, relying too heavily on these nontraditional tools could have unintended consequences. For example, if future policymakers responded to a severe recession by announcing their intention to keep the federal funds rate near zero for a very long time after the economy had substantially recovered and followed through on that guidance, then they might inadvertently encourage excessive risk-taking and so undermine financial stability.

Finally, the simulation analysis certainly overstates the FOMC’s current ability to respond to a recession, given that there is little scope to cut the federal funds rate at the moment. But that does not mean that the Federal Reserve would be unable to provide appreciable accommodation should the ongoing expansion falter in the near term. In addition to taking the federal funds rate back down to nearly zero, the FOMC could resume asset purchases and announce its intention to keep the federal funds rate at this level until conditions had improved markedly–although with long-term interest rates already quite low, the net stimulus that would result might be somewhat reduced.

Conclusion

Although fiscal policies and structural reforms can play an important role in strengthening the U.S. economy, my primary message today is that I expect monetary policy will continue to play a vital part in promoting a stable and healthy economy. New policy tools, which helped the Federal Reserve respond to the financial crisis and Great Recession, are likely to remain useful in dealing with future downturns. Additional tools may be needed and will be the subject of research and debate. But even if average interest rates remain lower than in the past, I believe that monetary policy will, under most conditions, be able to respond effectively.