The Financial Stability Institute has issued an occasional paper entitled “the “four lines of defence model” for financial institutions.” It takes the so called three-lines-of-defence model further to reflect specific governance features of regulated financial institutions. The paper highlights issues which exist in the current “recommended” approach, and specifically limitations of internal audit. Embedding the external auditors’ role in the structure of the defence system could mitigate the shortcomings of the traditional three-lines-of-defence model and increase the soundness and reliability of the risk management framework.

Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–09, the design and implementation of internal control systems has attracted serious academic and professional attention. Much research on the effectiveness and characteristics of internal audit functions has been conducted under the sponsorship of the Institute of Internal Auditors Research Foundation (IIARF) and published in academic and professional journals. The guidelines issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) in 2015 on corporate governance principles for banks emphasise the importance of proper risk management procedures, including, in particular, “an effective independent risk management function, under the direction of a chief risk officer (CRO), with sufficient stature, independence, resources and access to the board.” Furthermore, “the sophistication of the bank’s risk management and internal control infrastructure should keep pace with changes to the bank’s risk profile, to the external risk landscape and in industry practice” so as to identify, monitor and control risks on an ongoing bank-wide and individual-entity basis.

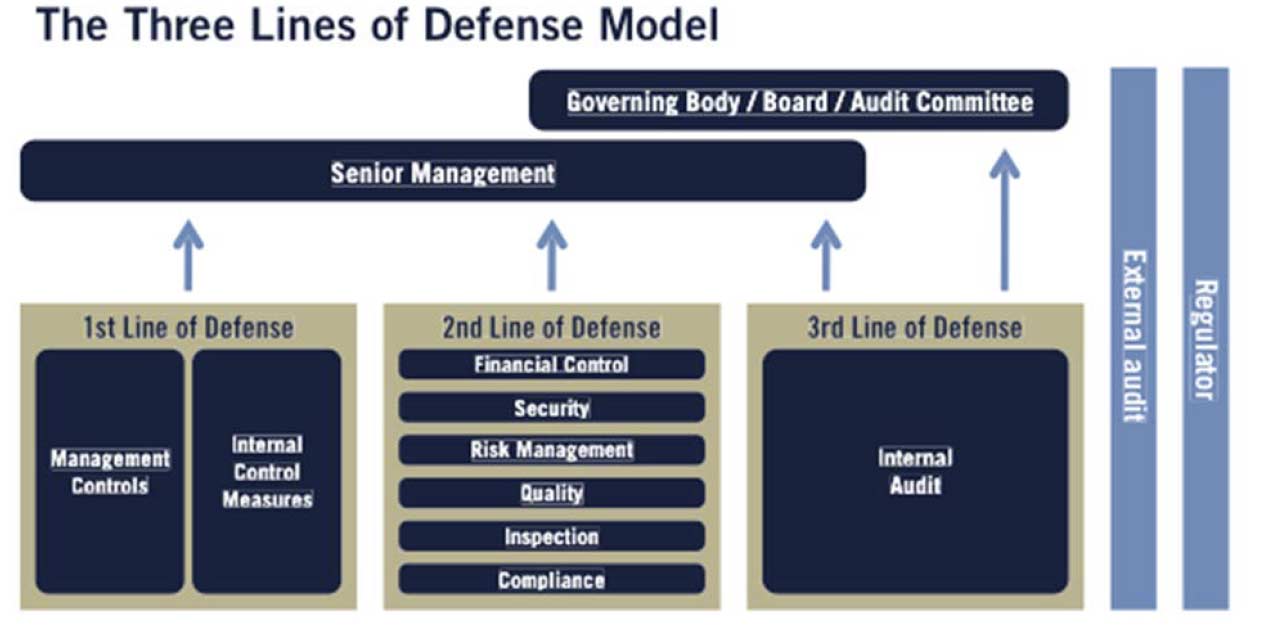

Despite these efforts, there has been little systematic analysis of how the design of an internal control system affects the efficiency and effectiveness of corporate governance processes, especially at financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies. The “three lines of defence model” has been used traditionally to model the interaction between corporate governance and internal control systems.

Recent significant risk incidents and corporate scandals caused by misconduct in financial market operations indicate that banks need to further enhance corporate governance measures. But, most importantly, such incidents have led to a further prioritisation of governmental and supervisory agendas relating to the potential systemic implications of weak internal control systems. This calls for a greater prominence of microprudential policies relating to misconduct at banks. It also calls for closer cooperation between regulators, and external and internal auditors, so as to win back public trust in financial institutions.

Recent significant risk incidents and corporate scandals caused by misconduct in financial market operations indicate that banks need to further enhance corporate governance measures. But, most importantly, such incidents have led to a further prioritisation of governmental and supervisory agendas relating to the potential systemic implications of weak internal control systems. This calls for a greater prominence of microprudential policies relating to misconduct at banks. It also calls for closer cooperation between regulators, and external and internal auditors, so as to win back public trust in financial institutions.

Specifically, four areas of weakness exist:

- Misaligned incentives for risk-takers in first line of defence

- Lack of organisational independence of functions in second line of defence

- Lack of skills and expertise in second line functions

- Inadequate and subjective risk assessment performed by internal audit

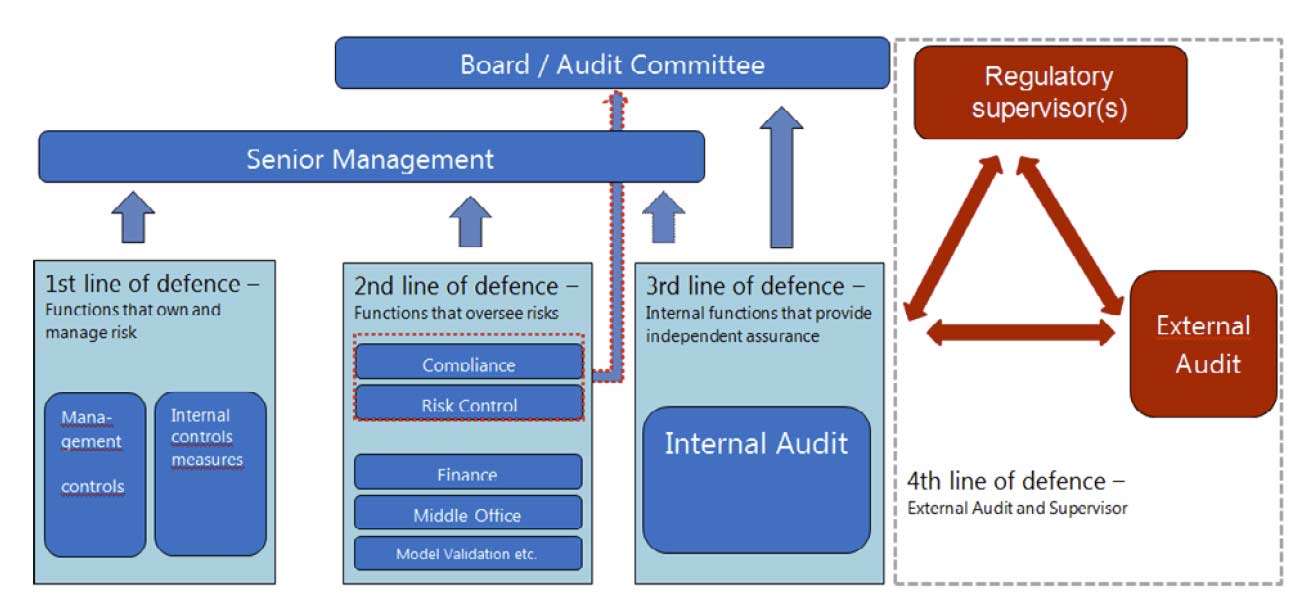

In order to account for the specific governance features of banks and insurance companies, they outline a “four lines of defence” model that endows supervisors and external auditors, who are formally outside the organisation, with a specific role in the organisational structure of the internal control system. Building upon the concept of a “triangular” relationship between internal auditors, supervisors and external auditors, they examine closely the interactions between them. By establishing a fourlines-of-defence model, they believe that new responsibilities and relationships between internal auditors, supervisors and external auditors will enhance control systems. That said however, they also highlight the risk that new problems could be caused by inadequate information flows among those actors.

Building upon the concept of a “triangular” relationship between internal auditors, supervisors and external auditors, they examine closely the interactions between them. By establishing a fourlines-of-defence model, they believe that new responsibilities and relationships between internal auditors, supervisors and external auditors will enhance control systems. That said however, they also highlight the risk that new problems could be caused by inadequate information flows among those actors.

Regulatory capital ratios, as well as other indicators of financial strength, such as liquidity and leverage ratios, are produced alongside banks’ standard financial reports but are not audited in the same way. This may create an expectations gap for society: what may be a bank’s most looked-at indicator is not audited. External auditors could perform assurance tasks related to such regulatory requirements (including capital ratios and risk-weighted assets, and leverage and liquidity ratios). Requirements for the independent scrutiny of regulatory capital information have evolved piecemeal across the world; some countries mandate publically available assurance reports, some only require financial institutions to inform regulators while others have no reporting requirement whatsoever. Given the size and importance of the banking sector – and the systemic risk posed to global financial markets – credibility and reliability are crucial.

They explored developments in a number of countries to illustrate the importance of increased cooperation between bank supervisors and external auditors:

1. United Kingdom:

The Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) of the United Kingdom recently issued a consultative document59 laying out the rules for external auditors of the largest UK banks for the provision of written reports to the PRA as part of the statutory audit cycle. The PRA asked external auditors to contribute to its supervision of firms by directly engaging in a pro-active and constructive way to support judgment-based supervision and help promote the safety and soundness of firms supervised by the PRA. The insights gained by auditors when they carry out high-quality audits should help enhance the effectiveness of the relationship between the auditors and the supervisor.

There have been improvements in the last few years such as a closer and more frequent engagement between supervisors and external auditors. The PRA keeps monitoring the quality of auditor-supervisor dialogue. In a survey of external auditors, it was noted that the vast majority of engagements was considered only ‘reasonable’ and that the PRA’s aim was to improve this engagement in the longer term. In particular, in individual cases both supervisors and auditors considered that there was room for improvement in the frankness with which information was shared, how often it was shared and what was covered in bilateral meetings.

2. Switzerland:

For many years, the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) has adopted a dualist approach whereby on-site examinations are outsourced to approved and licensed external auditors. A recent IMF assessment 60 noted significant weaknesses in Swiss supervision. FINMA should provide more guidance to auditors to ensure greater supervisory harmonisation across entities and should complement the auditors’ work with its own in-depth examinations of selected issues. In addition, the payment of auditors by a supervised entity was viewed critically as auditors should not be paid by a supervised entity but rather by a “FINMA administered bank-financed fund”. The IMF also noted that FINMA’s on- and off-site supervisory resources had been increased in recent years but still needed to be strengthened. Resources were insufficient to supervise and regulate the entire banking system in a way that met the Core Principles for Banking Supervision, including sufficient in-depth on-site work and oversight of supervisory work done by external auditors, particularly for small- and medium-sized banks.

3. United States:

A recent IMF report examined the relationship between supervisors and external auditors, and noted “that supervisors meet periodically with external audit firms to discuss issues of common interest relating to bank operations”. It also noted that there was no “safe haven” protection for external auditors in reporting issues to regulators. However, according to Part 363 of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) rules, a bank must inform its supervisor within 15 days of having received written information from the auditors about a violation that was committed. This gap is somehow mitigated by the frequent contact between supervisors and auditors in the course of examinations and planning. Furthermore, although the supervisors cannot set the scope of the external audit, they could encourage the auditors to include new issues. However, the report highlighted weaknesses relating to the fact that supervisors do not have legal powers to add specific issues to the scope of the external audit in order to address issues that are not normally covered by such an audit.

4. Hong Kong:

The Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) devotes significant efforts to ensuring effective communication channels with external auditors. Furthermore, its powers to commission external auditor reports for supervisory purposes further supports the relationship between the HKMA and the external auditors, and the understanding of the HKMA’s supervisory concerns. However, a recent IMF report63 states that there are two areas in which the HKMA lacks powers and where the legislative framework could be enhanced: the HKMA lacks powers to reject the appointment of an external auditor, when there are concerns over its competence or independence, and it does not have direct power to access the working documents of the external auditor even though the HKMA is able to address issues that arise by indirect means. While the HKMA has been able to work around these restrictions, amendments to the relevant legislation should be made.