“The Great Distortion.” That’s what The Economist, in its cover story of May 2015¸ called the systematic tax advantage of debt over equity that is found in almost every tax system.

This “debt bias” is now widely recognized as a real risk to economic stability. A new IMF study argues that it needs to feature more prominently on tax reform agendas; it also sets out options for how to do that.

Debt bias: Why we should (still) worry

The IMF’s recent Fiscal Monitor shows that global debt levels have risen to a record 225 percent of world GDP. And high corporate debt poses significant economic stability risks—especially in the financial sector: no one needs any reminder of the enormous damage from distress and failure of large financial institutions.

Since the global financial crisis, many governments have strengthened policies to mitigate excessive corporate borrowing, notably by tightening regulatory capital requirements for financial institutions.

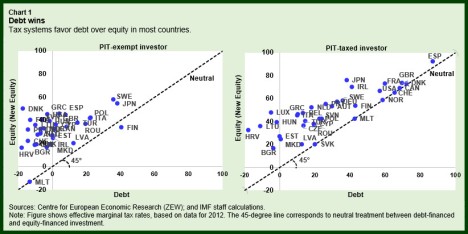

That’s good. But most tax systems continue to do exactly the opposite: they allow interest to be deductible, but not the costs of equity finance, and so encourage corporations to finance themselves through debt rather than equity. Chart 1 clearly shows that this tax discrimination in favor of debt is still widespread.

In advanced economies, the tax bias has increased debt ratios in nonfinancial corporations by, on average, 7 percent of total assets (about 15 percent of GDP). Our new results find that, despite their special status, financial institutions show a very similar response. Debt bias thus amplifies financial and macroeconomic stability risks—and the effect is too big to keep ignoring.

What can be done?

There are two broad ways to mitigate debt bias: limit the tax deductibility of interest, or provide a deduction for equity costs. There is now plenty of experience with both.

Limiting interest deductions

Some 60 countries have some form of limitation on interest deductibility. The details of the rules on these limitations vary greatly—and those details matter.

- 39 countries apply the limitations only to “related-party” debt (between affiliates within a multinational group). New analysis reported in our paper finds that (as one might expect) these rules have no discernable impact on firms’ borrowing from unrelated parties—which is what gives rise to stability concerns.

- 21 countries have rules applicable to all debt, related party or not. On average, these rules do reduce the external debt-to-asset ratio by around 5 percentage points—a significant effect.

Limitations on interest deductibility thus can work, but only if they cover all forms of debt.

Allowing a deduction for equity

Several countries—Belgium, Cyprus, Italy, and Turkey—have introduced an allowance for corporate equity (ACE). This retains the deduction for interest but adds a similar deduction for the normal return on equity.

Economists tend to like the ACE: it neutralizes debt bias and also eliminates tax distortions to investment. And the allowance continues to win over policymakers: Switzerland will soon introduce it, the Danish government has recently proposed its adoption, and the European Commission included it in its recent proposal for a common corporate tax base in the European Union.

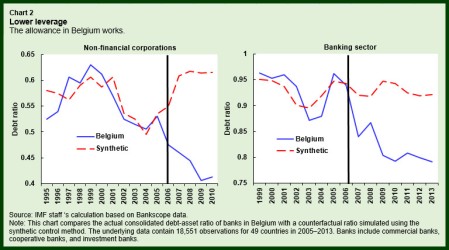

And the ACE works. Chart 2 reports new evidence on the effect of the Belgian allowance on corporate debt ratios in nonfinancial firms (left) and banks (right), relative to a synthetic control group of companies in other countries.

The impact is significant and large: the debt ratio in Belgium is almost 20 percentage points lower than in the control group for nonfinancial firms and almost 14 percentage points lower than in the control group for banks.

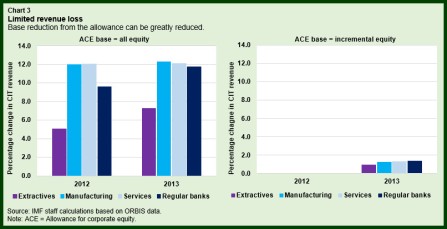

The main hesitation about the ACE is the potential revenue loss. We find that if the allowance were given to all equity, corporate income tax revenue would fall by 5-12 percent (Chart 3, left panel).

But governments can reduce the revenue cost while preserving the efficiency gains from the ACE by giving it only in respect to equity added after some base year—as is done in Italy and Switzerland and has been proposed in Denmark and by the European Commission.

This reduces the first-year revenue cost to about 1 percent of corporate income tax revenue (Chart 3, right panel). In the financial sector, moreover, the allowance might be granted only for equity above what is already required due to minimum regulatory capital requirements, which would further reduce the fiscal costs.

No better moment

Since the global crisis, debt bias has become much more widely recognized as a real macroeconomic concern. Governments have taken some steps to fix the distortions it creates.

But the issue has not gone away, and in the financial sector, tax policies (which encourage debt finance) and regulatory policies (which do the opposite) continue to be fundamentally misaligned. In our view, debt bias needs to figure more prominently in countries’ corporate tax reform agendas. The approaches discussed here have proven effective, and they can be tailored to countries’ circumstances. The revenue impact is currently muted by low interest rates. There will be no better moment than now to address the “Great Distortion” once and for all.