Australians saved rather than spent most of the budget tax cuts, almost doubling the proportion of household income saved, leaving spending languishing. Via The Conversation.

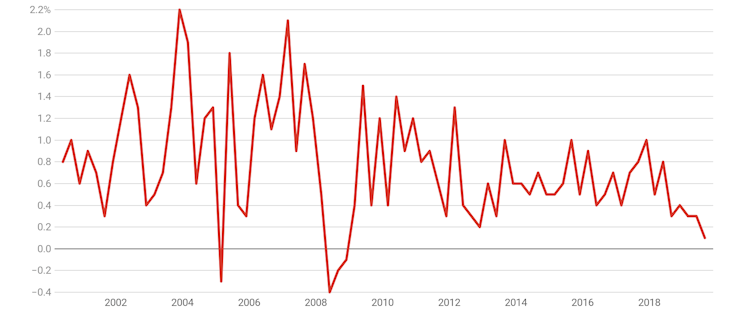

The September quarter national accounts show that in the first three months of the financial year real household spending grew by just 0.1%, the least since the global financial crisis.

Over the year to September, inflation-adjusted spending grew by a mere 1.2%, also the least since the financial crisis. Australia’s population grew by 1.6% in that time, meaning the volume of goods and services bought per person went backwards.

Quarterly growth in household spending

Separate figures released by the Federal Chamber of Automotive Industries on Wednesday show November new car sales were down 9.8% on November 2018.

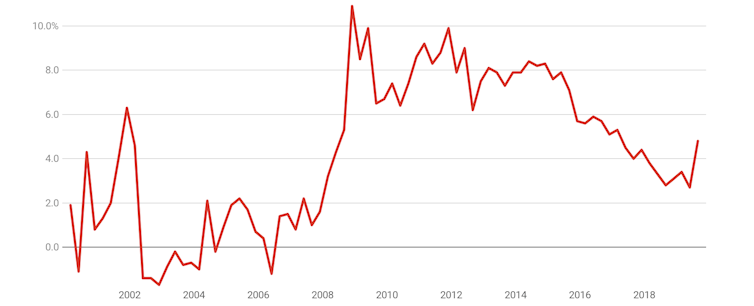

By the end of November the Tax Office had issued more than 8.8. million tax refunds totalling A$25 billion, 30% more than a year before.

Instead of being largely spent, they were mostly saved, pushing up the household saving ratio from 2.7% to 4.8%, its highest point in more than two years.

Household saving ratio

Treasurer Josh Frydenberg put the best face on the result, saying whether they had been spent or saved, the cuts had put households in a stronger position.

The government’s goal has always been to put more money into the pockets of the Australian people, and it’s their choice as to whether they spend or save that money

Separately calculated retail figures show that in the three months to September the volume of goods and services bought fell 0.1%.

The disposable income households had available to spend grew an outsized 2.5%, driven by what the Bureau of Statistics said were the budget tax cuts.

Growth at GFC lows

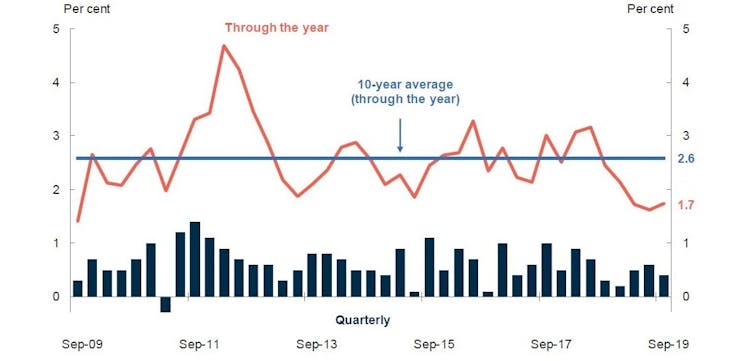

The Australian economy grew just 0.4% in the three months to September, down from 0.6% in the June quarter, and 0.5% in the March quarter.

Over the year to September it grew 1.7%, well short of the budget forecasts, which in year average terms were 2.25% for 2018-19 and 2.75% for 2019-20.

Real GDP growth

After taking account of population growth, GDP per person grew not at all in the September quarter. Over the year to September living standards grew a bare 0.2%.

Gross domestic product per hour worked, which is a measure of productivity, fell 0.2% during the quarter and fell 0.2% over the year.

Company profits were up 2.2% in the quarter and 12.7% over the year. Wage and superannuation payments grew at about half those rates: 1.2% and 5.1%.

Housing investment was down 1.7% over the quarter and 9.6% over the year.

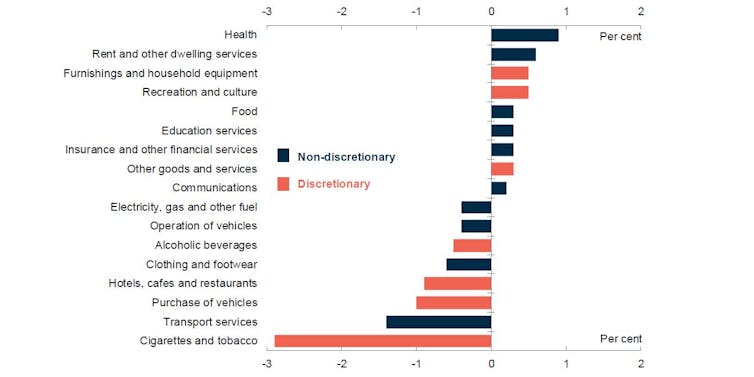

What household spending growth there was was concentrated on essentials, led by health and rent. So-called discretionary or non-essential expenditures fell, led down by spending on cars, dining out and tobacco.

Consumption growth by category, quarterly

The economy was kept afloat by a surge in government spending. It grew 0.9% in the quarter and 6% over the year. Growth in government spending and investment together accounted for 0.3 of the quarter’s 0.4 points of economic growth.

Government and mining to the rescue

Mining production grew 0.7% over the quarter and 7.4% over the year. A mining-fuelled surge in exports (which eclipsed imports for the first time since the 1970s) contributed almost as much to economic growth as government spending.

Drought-affected farm production fell 2.1% over the quarter and 6.1% over the year.

Business investment fell 4% in the quarter and 1.7% over the year, led down by a 7.8% fall in mining investment in the quarter and a 11.2% fall over the year, as liquefied natural gas projects came to completion. Non-mining investment fell 0.4%.

Asked whether the December budget update would contain tax measures designed to boost business investment, the treasurer said he was in discussions with business. The update is expected in the week before Christmas.

There’s little evidence in today’s figures of the “gentle turning point” spoken about hopefully by the Reserve Bank governor as recently as Tuesday.

If things don’t pick by the bank’s first board meeting for the year in February, it is a fair bet it will cut its cash rate again. By then it will know what the treasurer did (or didn’t) do in the budget update and whether we decided to spend over Christmas.

Author: Peter Martin, Visiting Fellow, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University