On 27 May, Germany’s bank supervisor Bundesamt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) published a recommendation of the

national financial stability committee that would require banks to hold an additional 0.25% capital cushion against their domestic riskweighted

assets (RWAs). At the same time, BaFin indicated its intention to follow this recommendation, which would become binding after a 12-month transition period on 1 July 2020. Via Moody’s.

The announcement is credit positive for German banks because it will encourage those with tighter capital cushions to set aside additional funds for risks that could surface in the case of changes to the current macroeconomic environment, foremost those related to a potential underestimation of future credit risks in a cyclical downturn, risks to collateral values in residential mortgage lending or risks related to the future interest rates trajectory.

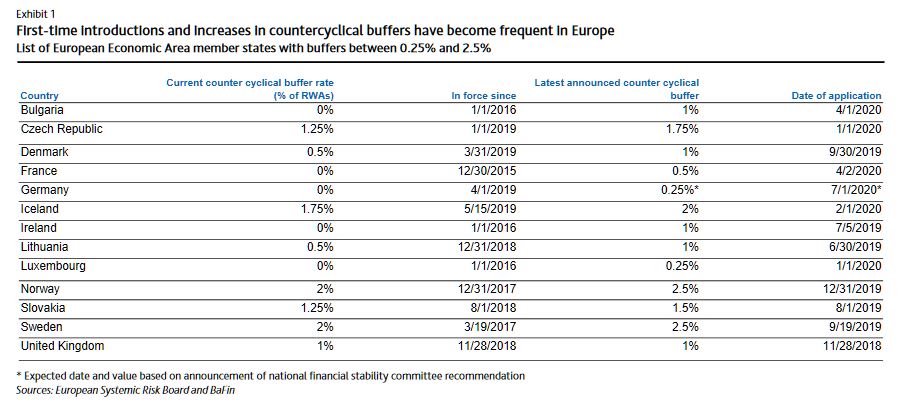

Germany is the 13th country in the European Economic Area to introduce a countercyclical capital buffer, and in most fellow member states the first step introduction has been followed by at least one increase later. Exhibit 1 provides an overview of initial and current countercyclical buffer (CCyB) requirements.

Germany’s 0.25% proposal will apply to German exposures of all European Economic Area banks and it remains very close to the bottom of the range compared with Norway and Sweden, whose CCyBs will reach the maximum of 2.5% later this year. Even so, we believe BaFin’s moderate first step and its ability to increase the requirement will lead German banks to further strengthen their capital buffers and it clearly signals BaFin’s aim to maintain the pace of systemwide RWA growth at a sound level. RWA growth, as a result of increased lending in combination with tighter RWA measurement rules, outpaced capital retention of Germany’s largest institutions during 2018 according to the supervisor, leading to declines in capital ratios.

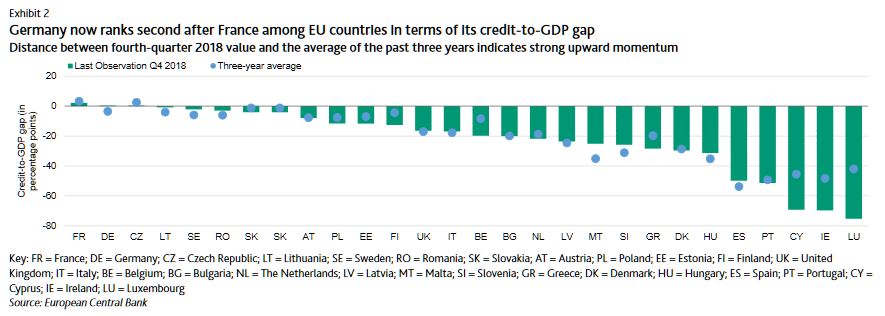

In setting the level of the CCyB, regulators are exercising their judgment while taking into account a range of factors including any deviation of the credit-to-GDP ratio from its long-term trend, asset price levels, business lending conditions, and any increase in the stock of nonperforming loans. While below the formulaic +2% threshold that would flag a potential need for raising the CCyB, exhibit 2 shows the German credit-to-GDP gap has been closing to a large extent in recent quarters.

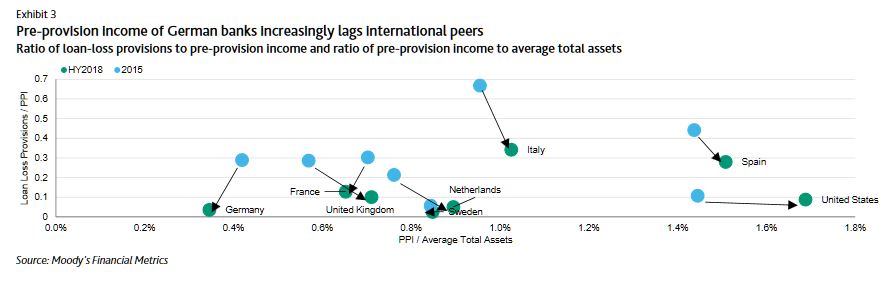

The German announcement echoes a recent recommendation by the International Monetary Fund, which had laid out a similar reasoning in the preliminary view of its annual Article IV mission which assesses the economic and financial development in the Germany. Regarding asset and profitability risks observed by the financial stability committee, we share the view that the German banking system’s current profitability is vulnerable once loan-loss provisioning needs normalise upwards, since the system’s preprovision income levels have further lost ground against international peers

While the sector’s continued prudence in new residential mortgage origination benefits banks, the financing of the banking sector’s long-term fixed-rate assets through current-account deposits results in asset-liability mismatch risks that we expect will at least in part become visible once interest rates rise and if they do so at a faster pace than the banks expected.